The partial genome of the thylacine or Tasmanian tiger has been sequenced and found to have extremely low genetic diversity.

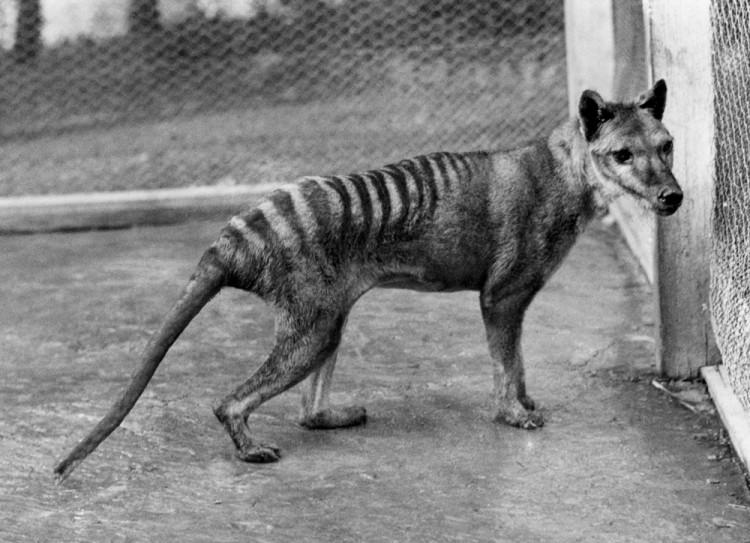

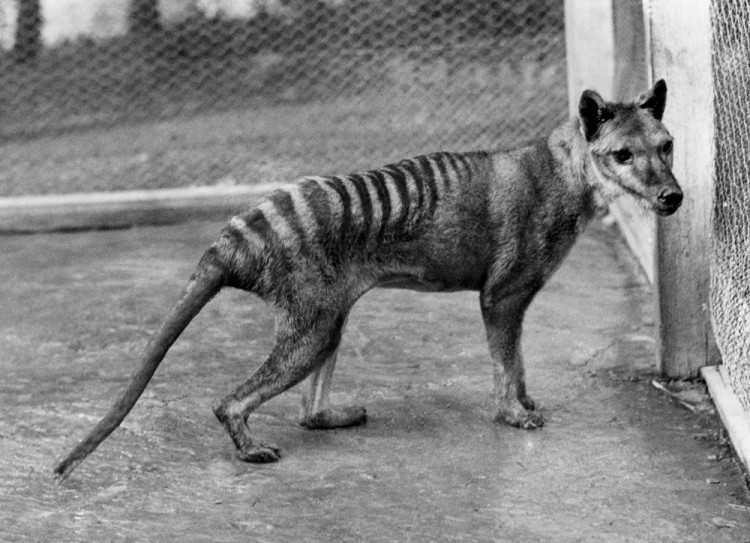

Thylacinus cynocephalus is believed to be extinct and looked like a medium-sized dog. The last known individual died in 1936 at a zoo in Tasmania.

“We found that the thylacine had even less genetic diversity than the Tasmanian devil,” said study senior author Andrew Pask at the University of Connecticut–Storrs in a press release.

“If they were still around today, they'd be at a severe risk, just like the devil.”

This stripey marsupial once inhabited both Tasmania and mainland Australia, which were linked by a land bridge until about 10,000 years ago. Thylacines on the mainland may have been outcompeted when dingoes were introduced, while hunters wiped out the tiger in Tasmania after it was labeled a livestock killer in the 1800s.

“It was completely unique, so its extinction was a massive loss,” Pask said.

The researchers sequenced part of the genome by analyzing samples from bones, skins, and preserved specimens with new and traditional techniques.

They found that the animals studied were 99.5 percent similar over a normally highly variable section of DNA, and 99.9 percent similar to the species’ mitochondrial genome, which has already been sequenced.

The scientists speculate that the thylacine’s genomic diversity was so low due to geographic isolation, similar to the devil, which is currently facing extinction due to the highly infectious Devil Facial Tumor Disease.

“It’s a sad situation, because right now there’s no cure for the tumor,” says Pask. “All we can do is take the populations that are not affected and breed them.”

Even if the Tasmanian tiger had not been hunted to extinction, its low genetic variation would have rendered it highly susceptible to disease.

“From a conservation standpoint, we need to know these things about animals’ genomes,” he said. “There are a lot of fragile animals in Australia and Tasmania.”

Pask said the thylacine’s complete genome will be sequenced next. “We really want to understand how a marsupial can look so much like a dog.”

The study was published in PLoS ONE on April 18.