During his first press conference as premier of the People’s Republic of China on March 17, Li Keqiang delivered a speech that was mostly unremarkable except for the fact that it included this innocent-seeming phrase: “We will be loyal to the constitution.”

Chinese Communist Party leaders regularly pad their speeches with empty promises of fealty to the law and ardent wishes to be “loyal to the people.” The reference to constitutionalism was different, however, because it was one of the first times that a top Party leader, except for Xi Jinping, has made the reference, and because, according to political analysts, the talk of constitutional rule has come to be a weapon that Xi is using to attack the influence of former Party leader Jiang Zemin.

A tangible example of Jiang’s continued influence is, in fact, the extent to which the spread of Xi’s remarks about constitutionalism has been curtailed in China. When one searches “dream of constitutionalism” (xianfa meng), in the major Chinese search engine Baidu News, there are a mere two results. A search on Google news brings two dozen.

According to an article by Chinese author Tie Liu, writing in Canyu Magazine, a dissident journal, this was due to an order from Liu Yunshan, a longtime Jiang man. From his perch in the Politburo Standing Committee, Liu is known to exercise control over the Ministry of Propaganda.

According to Tie, Liu Yunshan ordered that “One can only mention the China dream, not the constitutional dream. This is an absolute rule for the Party-controlled media. Violation of the rule will result in dismissal of the chief editor, removal of the editors, and suspension of the media.”

So it was that after Xi gave a speech about the constitution on Dec. 4 last year, little subsequent mention was made of it. Tie Liu writes: “It was like the firecrackers on New Year’s Eve. After the night’s over, you don’t hear the sound anymore. The word ‘constitution’ disappeared from the media.”

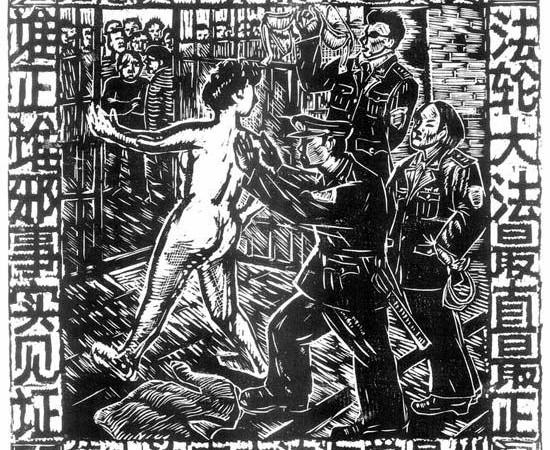

That was the case, at least, until Li Keqiang’s utterances on March 17. After mentioning the constitution, he then moved to another area that is no doubt a sore spot for Jiang Zemin’s faction: the dismantling of the re-education through labor system. “Certain government agencies are busy putting together the reform plan for the re-education through labor system,” Li Keqiang said.

For over a decade Jiang controlled the labor camp system, first through Luo Gan, and then through Zhou Yongkang, and the reform or closure of the camps is another point of conflict between the new regime and the old guard.

Li is officially the second-most powerful man in the Party, after Xi Jinping — a difference from his predecessor, Wen Jiabao, whose name was nearly always the third or fourth to be read by Chinese state media when the coterie of leaders emerged in public together. Party apparatchik Wu Bangguo was often put ahead of him (and when Jiang was on the scene, he would also be put ahead).

Xi Jinping has also been highlighting his crackdown on corrupt officials, and analysts say that many of Jiang Zemin’s underlings are being caught in its wheels. Li Chuncheng, for example, a trusted cadre of Zhou Yongkang’s in Sichuan Province, was taken down. Yi Junqing, a top communist theoretician for Jiang Zemin, was removed from his post in the Central Compilation and Translation Bureau. Liu Tienan, director of the National Energy Administration, and long rumored to be a financial manager for Jiang’s faction, was also purged recently.

Xi may seek to consolidate his power further before embarking on any major disruption of the status quo. Delaying Bo Xilai’s trial has become one such tool, insiders say, hinting that Bo may be hit with grave political charges in the latter half of this year.

Translation by Amy Xue. Research by Ariel Tian. Written in English by Matthew Robertson.

Read the original Chinese article.

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 21 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.