WASHINGTON—The U.S. Supreme Court begins hearing arguments for the October 2015 term on Monday, Oct. 5, with several cases of high public interest on its docket. Three high-profile cases involve resolving issues pertaining to constitutional law.

How the court this term decides on constitutional law questions is potentially far reaching. The outcomes could determine the future of affirmative action in college admissions, the power of unions in the public sector, and the relative strength in elections of the two major political parties. On the other hand, the court could decide each of these cases on narrow grounds that would limit their applicability and impact.

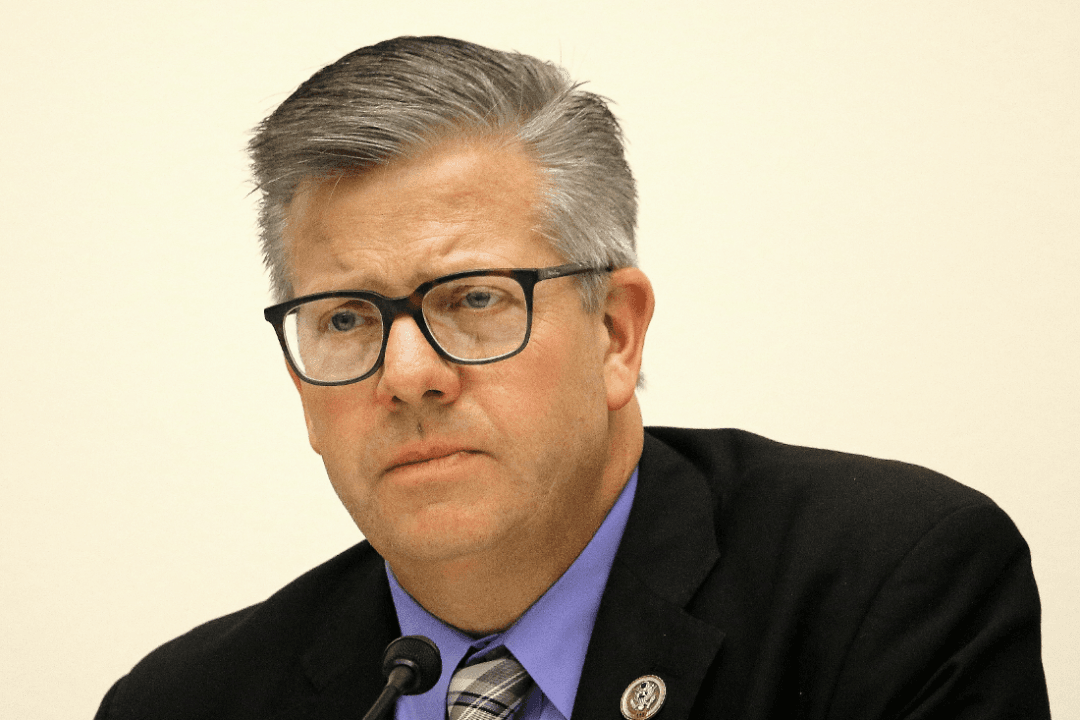

At a press briefing on Sep. 22 in the Georgetown University Law Center, five lawyers, each of whom has argued cases before the high court, discussed in detail what we can expect in this coming term.

Affirmative Action Challenged

Fisher v. University of Texas (Austin)

The University of Texas at Austin (UT) has made the case since 1992 that racial diversity is a worthy educational goal and “a compelling state interest” that benefits the learning environment of students. However, the Supreme Court has ruled in the past against anything that looks like the use of quotas. While the principle of race-based affirmative action has not been officially negated, affirmative action policies that seek to redress past discrimination have a very hard time passing the court’s rigorous scrutiny.

So UT came up with an admission policy that automatically admits students in the top 10 percent of their high school class. It’s a race-neutral policy that no one can challenge because race is not explicitly applied. It so happens that Texas high schools are highly segregated, which means some diversity is achieved from implementing this policy. By this top 10 percent rule, about 4 percent of the UT is African-American, and 15 percent Latino, said David Cole, constitutional law professor at Georgetown University Law Center.