The Supreme Court will consider whether it is constitutional to sentence juveniles to life in prison without the possibility of parole (known as JLWOP). The death penalty for people who commit crimes under the age of 18 was ended in 2005.

On March 20, the justices will hear arguments about two cases, Miller v. Alabama and Jackson v. Hobbs, which happened in Arkansas. Both offenders were 14 at the time of the murders. The question is whether their sentences violate the ban on cruel and unusual punishment in the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

In Jackson v. Hobbs, the offender did not commit the murder, according to his testimony. Kuntrell Jackson said he was not physically present, but was acting as a lookout while two other boys entered a video store and one shot the clerk.

In Miller v. Alabama, Evan James Miller was convicted of attacking his next-door neighbor, Cole Cannon, and setting his trailer on fire. Cannon died from smoke inhalation. Yet both convicted murderers have the same sentence—the greatest punishment short of the death penalty.

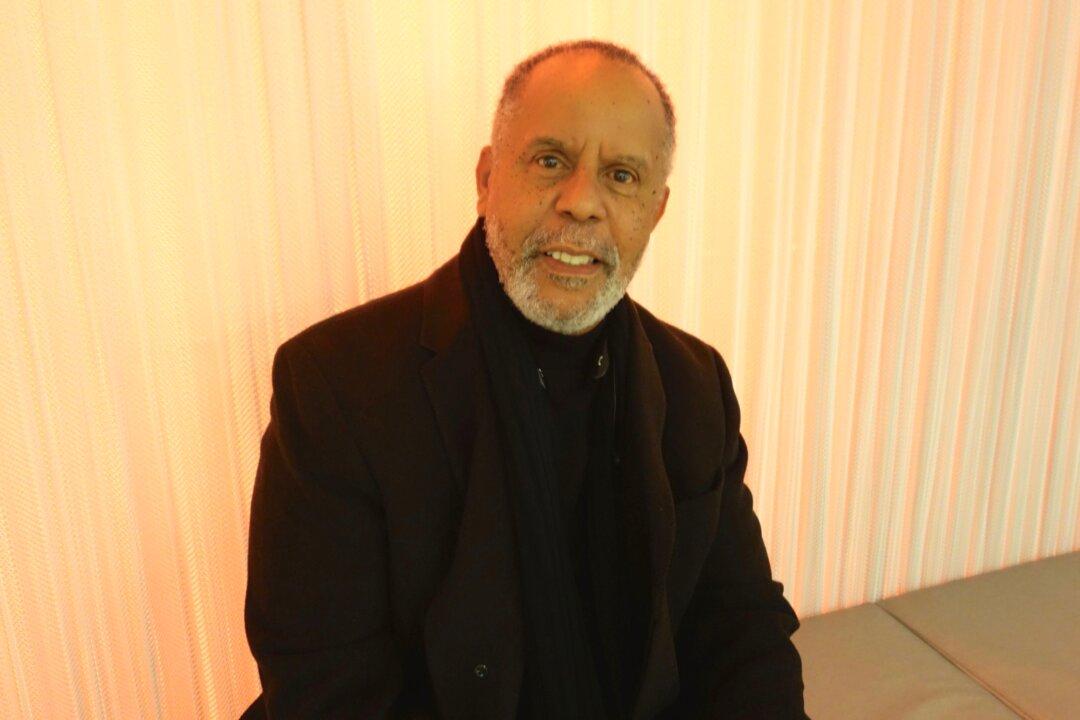

Brian Gallini, law professor at the University of Arkansas, said it is vitally important that the judges consider the two cases together.

Gallini is a national expert on juvenile sentencing. He said state legislators over time have added mandatory sentencing guidelines for certain categories of crimes, which leave judges with little discretion. “It’s like a bad storm.”

He said lawmakers, when trying to create mandatory sentencing guidelines, could not have looked forward and considered that the guidelines might have led to nonparticipants getting the same sentence as actual murderers. An accessory to felony murder, like Jackson, can be legally treated the same as the person who committed the crime, according to Gallini.

According to a report from the Sentencing Project, an advocacy group opposed to JLWOP, 33 states allow JLWOP.

According to the National District Attorney’s Association, the current sentencing guidelines for juveniles allow flexibility, and the LWOP sentence is rarely and wisely applied. In a brief to the Supreme Court, they wrote that it is not unconstitutional to apply JLWOP. “The question presented here is whether this court should jettison that holistic approach in favor of the bright-line rule that a 14-year-old may never, under any circumstances, be sentenced to life without parole. Amicus respectfully submits that the Eighth Amendment provides no warrant for any such categorical rule.”

To Gallini, an important issue is overly harsh sentences applied despite the facts of individual cases. “Courts continue to impose identical sentences on juvenile offenders who have drastically different roles in the crimes for which they were convicted,” said Gallini in a press release from the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. “This is because current Eighth Amendment standards, as interpreted by the Supreme Court, do not provide sentencing courts with the analytical tools necessary to account for stark differences in fact scenarios.”

He predicted that the judges might focus narrowly on the age of the offenders, and address the constitutionality of LWOP for someone who was 14 when a crime was committed. Or it may, as he recommends, tackle the problem of treating accessories to murder the same as murderers.

“The determinate sentencing of juvenile accomplice non-killers is inconsistent with what is left of the rehabilitation-based approach to juvenile criminal justice,” Gallini said in the press release.