Albert Florence was arrested in New Jersey during a traffic stop in 2005. Police arrested him for a mistaken bench warrant over an unpaid fine, which he had already paid. Florence went to jail, where he was searched after disrobing. He said his 4th Amendment protection against unreasonable search and seizure was violated, as well as his 14th Amendment rights. He essentially said his arrest warrant was not for an indictable crime, and therefore he should not have been treated as a criminal.

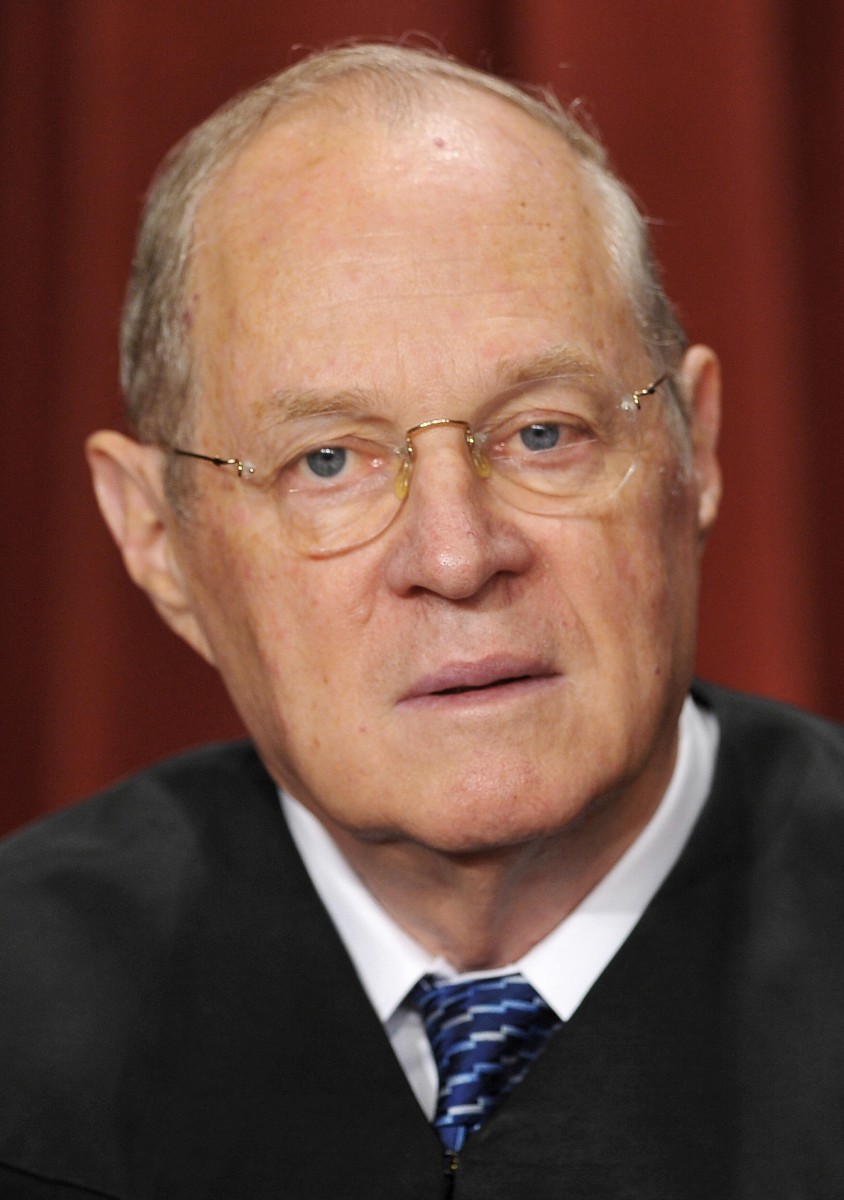

Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy and four colleagues overturned a lower court ruling that had agreed with Florence. Kennedy wrote that the searches are necessary for the safety both of corrections officers and their prisoners.

Treating people who are detained for minor offenses differently than those who could be accused of serious crimes is unsafe, according to Kennedy. “People detained for minor offenses can turn out to be the most devious and dangerous criminals. … Hours after the Oklahoma City bombing, Timothy McVeigh was stopped by a state trooper who noticed he was driving without a license plate.” Incoming prisoners who could be armed pose a potentially deadly danger to their jailers, Kennedy wrote.

Avoiding an unclothed inspection is also unsafe for the detainees, Kennedy wrote. If a certain class of prisoners is exempt from search, other inmates may coerce members of that class of prisoners to carry contraband. It is necessary to see if an incoming detainee is injured, has a contagious condition, or has the marks of gang affiliation. Gang members are dangerous and should be identified and isolated from the rest of the population, according to Kennedy.

He said that jail and prison officials must be allowed to do what they think is needed, even in cases where prisoner’s rights are violated. “The court has confirmed the importance of deference to correctional officials and explained that a regulation impinging on an inmate’s constitutional rights must be upheld ”if it is reasonably related to legitimate penological interests.”

Of the nine justices, four disagreed with the majority.

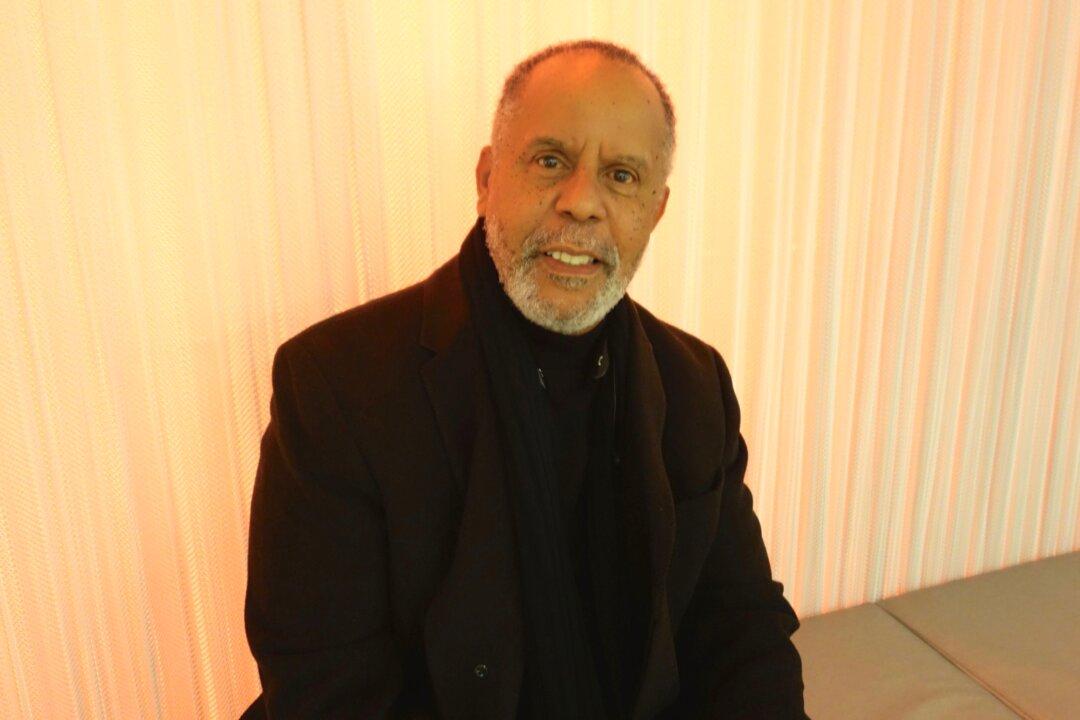

Justice Stephen Breyer wrote the dissenting opinion in Florence v. County of Burlington, in which he found some common ground with the majority. “I doubt that we seriously disagree about the nature of the strip-search or about the serious affront to human dignity and to individual privacy that it presents.”

The question was whether the “affront” was justified by what Kennedy described as concern for the safety of jailers and inmates, and the legitimate need to find contraband and weapons, according to Breyer.

He wrote that it was not justified. Penological needs must not be exaggerated to justify impinging on prisoner’s constitutional rights—and according to Breyer, the needs were exaggerated.

Applying a standard of probable cause to such searches would be just as effective in preventing weapons or contraband smuggling. Clothed searches, pat downs, and going through metal detectors already happen when a prisoner enters a jail. Those are sufficient unless probable cause exists to suspect the new inmate should be strip-searched, according to Breyer.

A strip-search as described would have little to do with identifying a person’s medical needs or wounds, Breyer wrote.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that no one disputed the facts of the case, but the justices interpreted the facts differently. He called for flexibility, “The court is nonetheless wise to leave open the possibility of exceptions, to ensure that we ”not embarrass the future.”