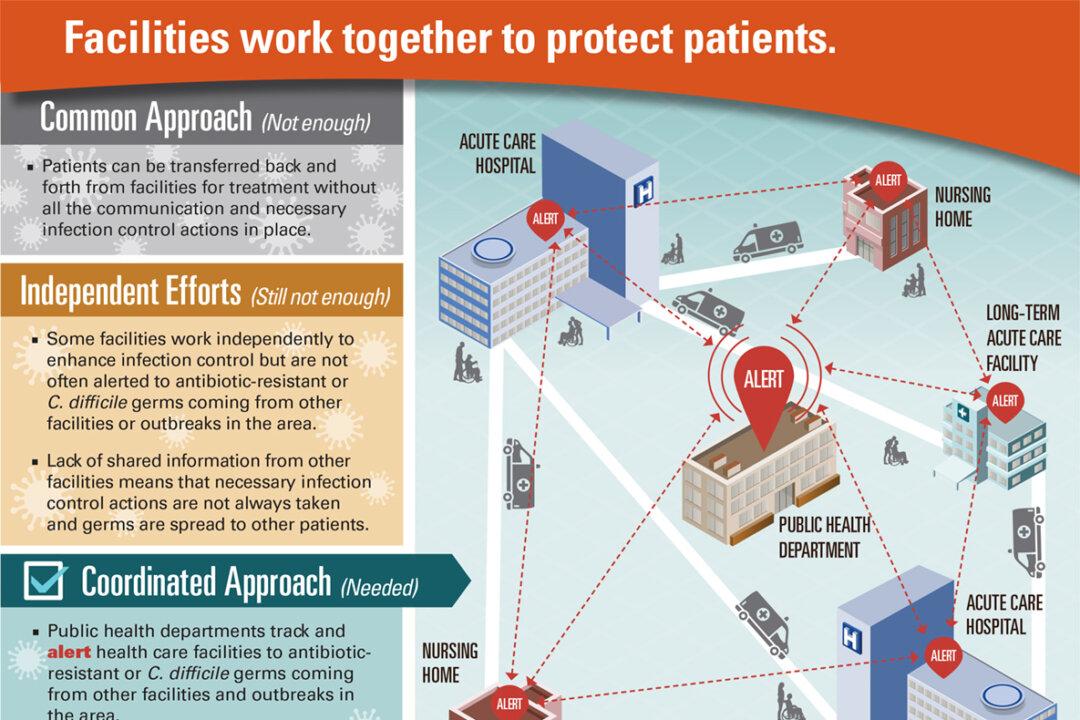

Unless health departments and hospitals coordinate care and practice good antibiotic stewardship, the superbugs will get the drop on us. According to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control, drug-resistant infections and Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) are set to spread.

We could enter a post antibiotic world in our lifetime. If it’s our fate, I guess we will do the best we can to navigate such a world. But I hope we do not have to.

Last weekend my brother-in-law and others made a genealogical side trip to a Lutheran Church in western North Carolina, where generations and generations of his ancestors lay. As we went further back, the marble headstones got richer in lichens and more weathered, and harder to read. One thing stood out: how little time many of the respected forbears had on Earth. We speculated that many of them died of things a course of antibiotics could have fixed. That safety net we count on today could soon be lost.

The worst of the antibiotic-resistant superbugs is the deadly CRE (carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae), which has become immune to all or nearly all drugs.