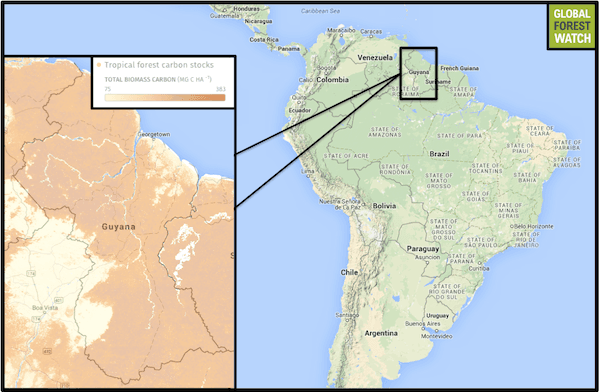

Some countries that retain forest wealth have started monetizing their forests using international programs like REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation). Guyana has been at the forefront of REDD efforts thanks to a supportive administration.

An important part of REDD is accurate measurement of carbon stocks. This is accomplished through a combination of remote sensing estimation and “ground truthing,” in which on-the-ground technicians physically travel to sites and collect data on forest cover to check whether or not the results from remote sensing procedures are correct.

In Guyana, members of native Amerindian communities have been recruited for data collection by Project Fauna, a joint initiative by researchers from different institutions and local indigenous leaders. José Fragoso from Stanford University and his lab was one of groups involved. The project’s aim was to “describe wildlife diversity and abundance and interactions between these elements and indigenous culture.”

Between 2007 and 2010, Project Fauna trained 335 indigenous technicians across 30 Amerindian communities in the Rupununi region. After the training, technicians were able to describe vegetation structure and monitor wildlife populations and hunting patterns. The project was a success and motivated Fragoso’s group to extend it to include carbon stock assessment through vegetation measurements. The pilot project for carbon measurement was implemented at 20 sites, which had eight categories of forests and both government-owned and community-owned forest areas. Local people were taught to sample and measure vegetation via intensive training programs that involved both classroom and field demonstrations.

“An important aspect of studies such as these is the sampling protocols followed,” Wayne Walker, an ecologist and remote sensing scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center in the US, who was not involved in the study, told mongabay.com. “Good quality data from the field is necessary to support the remote sensing data. This paper had a protocol that seemed representative of different vegetation types and different levels of carbon stocks.”

The field technicians measured aboveground biomass by measuring the girth of trees, consistently at breast height, across different forest types. Carbon stocks varied from a million tons per site to about 22.7 million tons, depending on the vegetation type, forest use patterns and stem density.

“We knew from past work that we could get high quality data produced by local people if they accepted the relevance of the work to their livelihoods, if we could provide stipends and if we could keep them motivated,” Fragoso, senior author of the study, told mongabay.com.

Monitoring, reporting and verification

An important step of this process, which adds a layer of confidence, is verification. As the authors Nathalie Butt, Kimberly Epps, Han Overman. Takuya Iwamura and Fragoso explain in the paper, there is an obvious vested interest in local landowners estimating carbon stocks in their own forests; but there could also be a tendency to overestimate carbon data, by recording higher tree girths than are correct, for example. To deal with defaulters and data discrepancies, the REDD/REDD+ protocol involves three steps: monitoring, reporting and verification —or MRV.

“The Guyana Forestry Commission is committed to Community Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) for those communities who choose to enroll their lands in Guyana’s REDD program, and continues to support training for communities in REDD and carbon monitoring,” Fragoso said.

The authors suggest various methods to ensure such conflicts are avoided: having multiple teams measuring the same vegetation type, cross-checking sites using different teams, re-measuring plots with discrepancies and adding penalties like disqualification from payment schemes.

“We did replace technicians on the project when we found they were unmotivated or fabricated data,” Fragoso said. “These problems will always be there. The project team, including community leaders, just has to be prepared for this. In our past work, we detected about 5 percent of local technicians fabricating data. This compares to about 7 percent of scientists fabricating data as reported in the journal Nature recently.”

The idea of using indigenous people for biodiversity monitoring is not new at all, but this study is one of the few to systematically examine the usefulness of such data by comparing the data collected by local technicians to those collected by scientists. “The [tree trunk diameter at breast height] values did not differ significantly between the two datasets,” Fragoso said. “The comparison speaks favourably about the quality of the data.”

In total, the researchers found more than 92 percent of the data collected was valid and could be used in analysis. While this was a local study, Fragoso asserted this system can be applied in other places.

“We believe indigenous and rural people anywhere can do the work, with occasional input by researchers,” Fragoso said. “Part of the reason for the project was to see whether it was possible to establish, through appropriate training, the conditions under which Amazonian indigenous people living in remote locations could do the work. We had at least five languages being spoken, although many also spoke English. There were people who were illiterate and with little to no schooling. These were coupled with people who were literate to some degree. The results show that yes, with the right trainers who understand the context and training needs, and with people who have the motivation to understand and do the work, this is replicable.”

Walker agrees, underlining the value of employing local people in data collection. “Based on my experience, there is no doubt that data can be collected accurately by indigenous people. Especially when they have been well trained,” he said.

The advantages of such a system are obvious: local technicians know the areas best; they are available at hand for continuous monitoring; it is less expensive to use them than to transport experts across hundreds, even thousands, of miles. It is a method of scientific capacity building that brings economic benefits to local communities. “It is overall so much more efficient,” Walker said. “Most importantly, it is appropriate that local people should be involved in surveying their land.”

An added benefit is that by being part of the process, local people can come to understand how much their forests are worth in terms of carbon stock.

“It has all been positive so far from indigenous people,” Fragoso said. “They were pleased to see the validation of their work.”

Citations:

- Butt, N., Epps, K., Overman, H., Iwamura, T., & Fragoso, J. M. (2015). Assessing carbon stocks using indigenous peoples’ field measurements in Amazonian Guyana. Forest Ecology and Management, 338, 191-199.

- Saatchi, S.S., N.L. Harris, S. Brown, M. Lefsky, E. Mitchard, W. Salas, B. Zutta, W. Buermann, S. Lewis, S. Hagen, S. Petrova, L. White, M. Silman, and A. Morel. 2011. “Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences vol 108, no. 24, pp 9899-9904. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1019576108.

This article was written by Sandhya Sekar, a correspondent writer for news.mongabay.com. This article is the second part in a series of two articles covering this topic, first article here. This article is republished with permission, original article here.