NEW YORK—The Van Dyke Money Gang in New York made off with more than $1.5 million this year—but it wasn’t in gunpoint robberies or drug running, it was a Western Union money order scheme. In New Jersey, 111 Neighborhood Crips used a machine to make dozens of fake gift cards for supermarkets, pharmacies and hardware stores. In South Florida, gangs steal identities to file false tax returns.

These aren’t members of an organized Mafia or band of hackers. They’re street crews and gangs netting millions in white-collar schemes like identity theft and credit card fraud—in some instances, giving up the old ways of making an illicit income in exchange for easier crimes with shorter sentences.

“Why would you spend time on the street slinging crack when you can get 10 years under federal minimums when in reality you can just bone up on how to make six figures and when you get caught you’re doing six months?” said Al Pasqual, director of fraud security at the consulting firm Javelin Strategy and Research.

Law enforcement officials say they see increasingly more gangs relying on such crimes. This year, more than three dozen suspected crew members have been indicted in separate cases around the country. Grand larcenies in New York City account for 40 percent of all crime last year—compared with 28 percent in 2001. About 5 percent of Americans nationwide have experienced some kind of identity theft, with Florida leading the country in complaints.

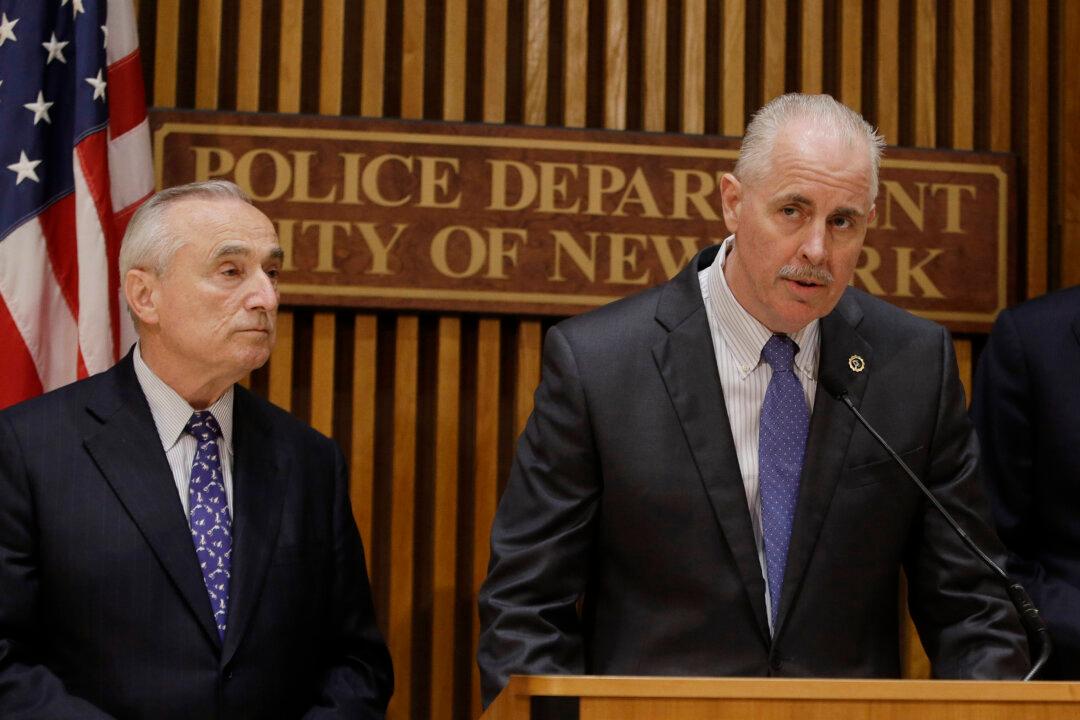

New York Police Commissioner William Bratton wrote in an editorial in the city’s Daily News last week that white-collar crime was being committed by gang members “to an astonishing degree.”