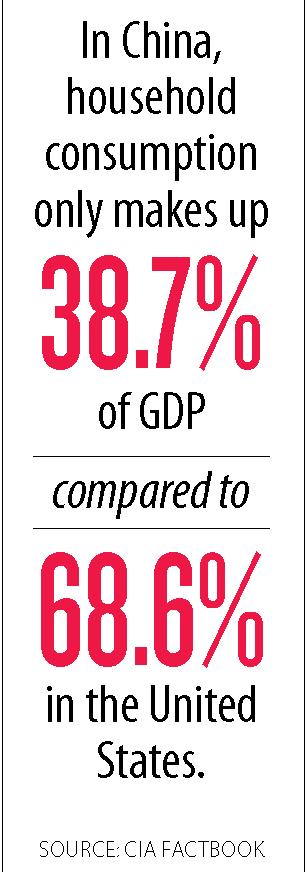

Given the notorious unreliability of official Chinese economic data, analysts risk getting it wrong when relying solely on figures the government puts out. Is the China growth story, and a rebalance from manufacturing to consumption, actually happening? Or is the country’s enormous debt, with semi-bankrupt, state-owned enterprises and widespread overcapacity, still the overriding concern?

To shed light on these murky issues, Leland Miller and his team at China Beige Book International (CBB) interview thousands of companies and hundreds of bankers on the ground in China each quarter to get an accurate gauge of how the economy is doing.

*