NEW YORK—Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s Common Core panel has recommended the state stop working with inBloom Inc., a nonprofit that has fallen out of grace across the nation due to parents’ student data privacy concerns.

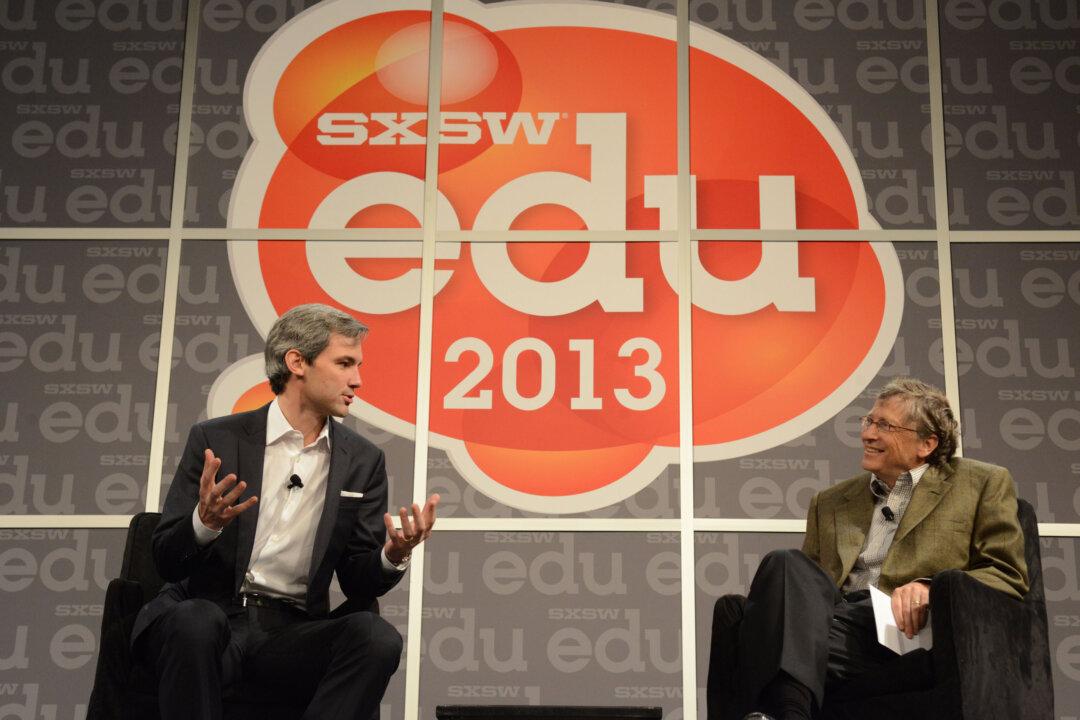

InBloom was established in 2013 with $100 million mostly from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation. The company collects student data, stores it in encrypted form on Amazon cloud servers, and makes it available in an organized format to companies contracted by school districts to create software tools.

Nine states initially signed up for the service, but all except New York later pulled out or put the plan on hold due to concerns over data privacy. Parents protested sharing sensitive data, most prominently the medical data of students with disabilities, and suspension records.

The Common Core Implementation Panel wasn’t primarily intended to deal with the issue of student data privacy. The governor set it up in early February to review how the state’s Common Core learning standards have been put into practice.

Common Core is a set of learning benchmarks. If met, it holds the promise that students who graduate from high school will be ready to enter college. Common Core has been accepted by 47 states, partly as a condition to win money from the federal grant program Race to the Top.

Race to the Top prompted some states to turn to inBloom as a method of storing and better analyzing student data, including the increased data generated by Common Core.

By and large, the panel’s recommendations regarding Common Core have already been proposed, or are being implemented by the board of regents, the state’s governing body for education.

One exception to this is the inBloom project. The regents wanted to delay it. Cuomo’s panel wants it gone.

InBloom Controversy

“The debate about this one provider has become a distraction to the successful implementation of the Common Core,” states the panel’s March 10 preliminary report. “The state’s relationship with inBloom should be halted, and state leaders should consider alternative paths to accomplish the goals of increased data transparency and analytics.”

State Education Commissioner John King Jr. has defended inBloom on multiple occasions, saying the student’s data is already provided to software developers—not just centrally, but on a district by district basis.

The panel addressed this fact as well, calling for legislative action giving parents “complete transparency about what data is collected by the state and by school districts, who it is shared with, and why.”

The panel also wants harsher penalties for violations leading to a data breach.

Still, the panel is against allowing parents to opt-out of sharing the data as it “could place essential academic and operational functions in jeopardy.”

Such sentiment is not shared by Leonie Haimson of Class Size Matters. She thinks schools districts just don’t want to bother with handling the opt-outs. “They think it would be too difficult and too much of a burden,” she said. “We’re not clear that it would be that difficult and we’re not at all clear that a lot of this data sharing that’s going on right now is really necessary.”

Class Size Matters, a nonprofit, helped a group of parents last year sue the state for releasing data to inBloom without parental consent. The lawsuit was not successful.

Haimson was cautiously optimistic about the panel’s recommendation to drop inBloom. “I’m not going to celebrate until it actually happens,” she said, pointing out that even if the state does so, it may just switch to a different company.

“They know that inBloom is too controversial now and they want to try a different route to, perhaps, the same problem.”