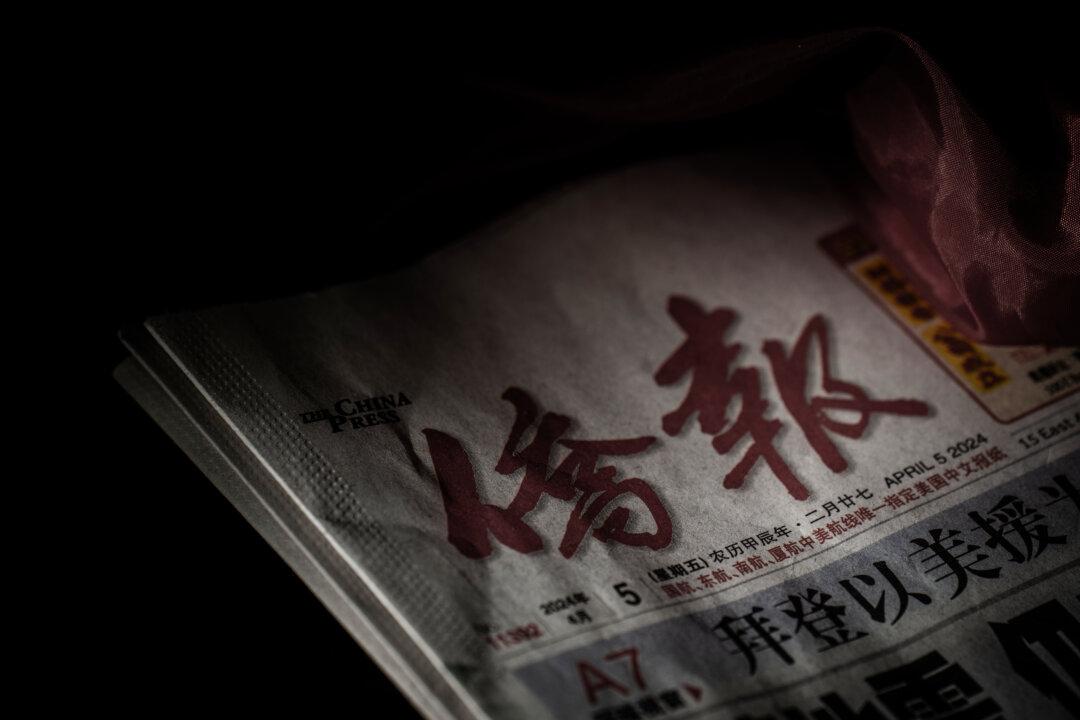

For years, one Chinese language media outlet in the United States has openly framed itself as serving immigrants from mainland China, using simplified Chinese characters as its appeal.

A look into its background reveals its deep ties with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).