Sony Pictures’ plight seems only to deepen in what is shaping up to be one of the most destructive and visible cyber attacks in U.S. corporate history. In a nod to their viral commercial “From Script to Screen”, the hackers from a group calling itself Guardians of Peace hacked and leaked everything Sony – unreleased films, scripts, medical records, social security numbers, home addresses and payroll for 47,000 employees, some going back as far as 1955. All in all, some 100TB of information was stolen and subsequently wiped clean from the company’s computers and servers. In one case, a woman’s breastfeeding diet was published. None of the names were redacted and the data is freely available to anyone knowing how to use torrents.

The FBI was called in to help and the investigation is still ongoing.

What happened

Over 40Gb of data was released to select journalists, most of it encrypted. Nevertheless, Buzzfeed reporters Charlie Warzel and Tom Gara sifted through the packet and their verdict is unforgiving: Sony “has suffered the most embarrassing and all-encompassing hack of internal corporate data ever made public.”

Sony initially blamed North Korea, claiming the hack was motivated by an upcoming flick with James Franco that talks about the assassination of Kim Jong-un at the hand of two journalists turned CIA henchmen. The country had threatened in the past “merciless retaliation” if the United States failed to ban the film from seeing the light of day. North Korea denied all wrongdoing and claimed that its government “publicly declared that it would follow international norms banning hacking and piracy”.

In spite of such “assurances” coming from one of the world’s most secretive nations, North Korea is the prime suspect in a similar malware attack that happened in 2013. In what was called the DarkSeoul incident, 30,000 computer systems belonging to South Korean media outlets and financial institutions were infected and then wiped clean of information.

But a week after the attack, the details of the case became even murkier. The Verge exchanged several emails with people alleging to be behind the hack. A person going by the name of “Iena” said that the group wanted “equality“ and that they had an inside man in Sony’s staff that helped them access sensible information. It is unclear what kind of equality the group was seeking, but several media reports detailed the ”stark gender pay gap“ practiced by Sony as well as the insufficient number of women in top managerial positions.

How it happened

According to Jaime Blasco, director of security management at AlienVault, who has seen samples of the malware in question, “we can say that the attackers knew the internal network”. The lines of code he obtained are partly written in Korean and contain hardcoded names of Sony servers and even login details (credentials and passwords) used to infiltrate the company’s internal network. Blasco’s assessment was subsequently verified by experts with PacketNinjas, who argued that the malware looks to have been tailored made for Sony.

The ferocity and extent of the hack, as well as the target chosen – a movie production company - are uncharacteristic for the type of attack mounted. Usually, these types of malware applications, known as “wipers”, are used with more strategic purposes in mind, such as crippling a country’s industrial infrastructure or as tools in an ongoing cyber war.

Their architecture consists of three separate modules: a dropper (the program designed to carry and install the malware), the wiper and the reporter. The second component works by overriding data on the target computer, including the master boot record (MBR) that contains information on how a drive is portioned and the code needed to run an operating system. Saudi Arabia’s national oil company, Saudi Aramco, fell victim in August 2012 to the Shamoon “wiper”, which infected and destroyed some 30,000 company computers and replaced the hard disks’ information with a picture of a burning American flag.

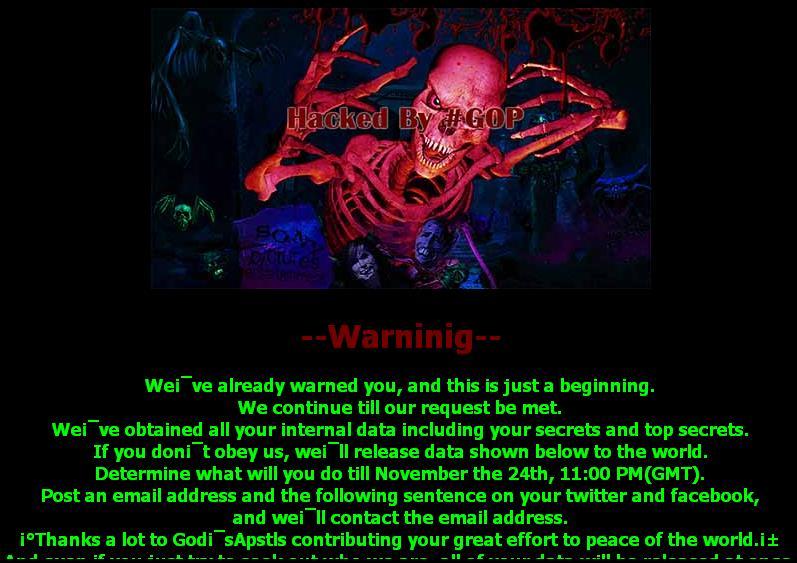

The wiper used in Sony’s case, Backdoor.Destover, bears striking similarities with both DarkSeoul and Shamoon. For example, the methods used to infect and damage the computer systems and are almost identical. What’s more, the three groups claiming credit for the hacks were unknown, disappeared after the attacks and did no make any clear statements. Both DarkSeoul and Shamoon used vaguely worded political messages to justify the attack. In Destover’s case, the attackers made their presence known by hijacking the infected machine’s desktop and displaying an ominous image with a red skeletal figure followed by a bizarre ransom text asking for obedience.

Kurt Baumgartner of Kaspersky Lab tried to dismiss claims that the attacks were carried out by the same group, but found curious that “such unusual and focused acts of large-scale cyber-destruction are being carried out with clearly recognizable similarities.”

The road ahead

Sony’s security breach was a long time coming. The vast majority of sensitive personnel and financial files were stored unencrypted on company servers. On the face of it, it seems like a clear case of cyber security mismanagement – even if the attackers used Sony employees to maximize the damage inflicted, there is simply no excuse for such a blatant lack of safeguards.

What’s clear is that Sony is now facing years of costly litigation with disgruntled employees and a significant blemish on its brand image. The total costs of the hack are hard to estimate at this point, but they are likely to take a significant toll on the company’s bottom line. But so far, the story is definitely worthy of a classic Hollywood whodunnit caper.