WASHINGTON—The detective work blaming North Korea for the Sony hacker break-in appears so far to be largely circumstantial, The Associated Press has learned. The dramatic conclusion of a Korean role is based on subtle clues in the hacking tools left behind and the involvement of at least one computer in Bolivia previously traced to other attacks blamed on the North Koreans.

Experts cautioned that hackers notoriously employ disinformation to throw investigators off their tracks, using borrowed tools, tampering with logs and inserting false references to language or nationality.

The hackers are believed to have been conducting surveillance on the network at Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc. since at least the spring, based on computer forensic evidence and traffic analysis, a person with knowledge of the investigation told the AP.

[aolvideo src=“http://pshared.5min.com/Scripts/PlayerSeed.js?sid=1759&width=480&height=300&playList=518566521&responsive=false”]

If the hackers hadn’t made their presence known by making demands and destroying files, they probably would still be inside because there was no indication their presence was about to be detected, the person said. This person, who described the evidence as circumstantial, spoke only on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to talk openly about the case.

Still, the evidence has been considered conclusive enough that a U.S. official told the AP that federal investigators have now connected the Sony hacking to North Korea.

In public, White House spokesman Josh Earnest on Thursday declined to blame North Korea, saying he didn’t want to get ahead of investigations by the Justice Department and the FBI. Earnest said evidence shows the hacking was carried out by a “sophisticated actor” with “malicious intent.”

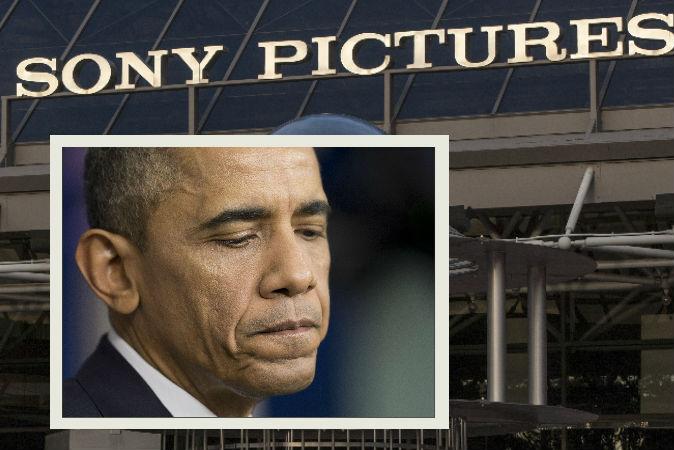

All this has led to a dilemma for the Obama administration: How and whether to respond?

An earlier formal statement by the White House National Security Council also did not name North Korea but noted that “criminals and foreign countries regularly seek to gain access to government and private sector networks” and said “we are considering a range of options in weighing a potential response. ” The U.S. official who cited North Korea spoke on condition of anonymity because that official was not authorized to openly discuss an ongoing criminal case.

MORE:

U.S. options against North Korea are limited. The U.S. already has a trade embargo in place, and there is no appetite for military action. Even if investigators could identify and prosecute the individual hackers believed responsible, there’s no guarantee that any who are overseas would ever see a U.S. courtroom. Hacking back at North Korean targets by U.S. government experts could encourage further attacks against American targets.

“We don’t sell them anything, we don’t buy anything from them and we don’t have diplomatic relations,” said William Reinsch, a former senior U.S. Commerce Department official who was responsible for enforcing international sanctions against North Korea and other countries. “There aren’t a lot of public options left.”

Sony abruptly canceled the Dec. 25 release of its comedy, “The Interview,” which the hackers had demanded partly because it included a scene depicting the assassination of North Korea’s leader. Sony cited the hackers’ threats of violence at movie theaters that planned to show the movie, although the Homeland Security Department said there was no credible intelligence of active plots. The hackers had been releasing onto the Internet huge amounts of highly sensitive — and sometimes embarrassing — confidential files they stole from inside Sony’s computer network.

North Korea has publicly denied it was involved, though it has described the hack as a “righteous deed.”

[aolvideo src=“http://pshared.5min.com/Scripts/PlayerSeed.js?sid=1759&width=480&height=300&playList=518566515&responsive=false”]

The episode is sure to cost Sony many millions of dollars, though the eventual damage is still anyone’s guess. In addition to lost box-office revenue from the movie, the studio faces lawsuits by former employees angry over leaked Social Security numbers and other personal information. And there could be damage beyond the one company.

Sony’s decision to pull the film has raised concerns that capitulating to criminals will encourage more hacking.

“By effectively yielding to aggressive acts of cyberterrorism by North Korea, that decision sets a troubling precedent that will only empower and embolden bad actors to use cyber as an offensive weapon even more aggressively in the future,” said Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., who will soon become chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. He said the Obama administration has failed to control the use of cyber weapons by foreign governments.

Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson said on MSNBC that the administration was “actively considering a range of options that we'll take in response to this attack.”

MORE:

- Sony’s ‘The Interview’ Poked at North Korea’s Biggest Taboo

- US Officials Say North Korea Behind Sony Hack, Studio Cancels ‘The Interview’ Release

The hacking attack could prompt fresh calls for North Korea to be declared a state sponsor of terrorism, said Evans Revere, a former State Department official and Northeast Asia specialist. North Korea was put on that American list of rogue states in 1988 but taken off in 2008 as the U.S. was involved in multination negotiations with the North on its nuclear weapons program.

Evidence pinning specific crimes on specific hackers is nearly always imprecise, and the Sony case is no exception.

Sony hired FireEye Inc.’s Mandiant forensics unit, which last year published a landmark report with evidence accusing a Chinese Army organization, Unit 61398, of hacking into more than 140 companies over the years. In the current investigation, security professionals examined blueprints for the hacking tools discovered in Sony’s network, the Korean language setting and time zone, and then traced other computers around the world used to help coordinate the break-in, according to the person with knowledge about the investigation.

Those computers were located in Singapore and Thailand, but a third in Bolivia had previously been traced to other attacks blamed on North Korea, the person told the AP. The tools in the Sony case included components to break into the company’s network and subsequently erase all fingerprints by rendering the hard drive useless.

“The Internet’s a complicated place,” said Adam Meyers, vice president of intelligence at CrowdStrike Inc., a security company that has investigated past attacks linked to North Korea. “We’re talking about organizations that understand how to hide themselves, how to appear as if they’re coming from other places. To that end, they know that people are going to come looking for them. They throw things in the way to limit what you can do attribution on.”

Another agreed. “If you have a thousand bad pieces of circumstantial evidence, that doesn’t mean your case is strong,” said Jeffrey Carr, chief executive of Taia Global Inc., which provides threat intelligence to companies and government agencies.

An FBI “flash” bulletin sent to some companies with details of the hacking software described it as “destructive malware, a disk wiper with network beacon capabilities.” The FBI bulletin included instructions for companies to listen for telltale network traffic that would suggest they had been infected.

Other movie studios aren’t taken chances. Warner Bros. executives earlier this week ordered a company-wide password reset and sent a five-point security checklist to employees advising them to purge their computers of any unnecessary data, in an email seen by The Associated Press.

“Keep only what you need for business purposes,” the message said.

Timeline of the Sony Pictures Entertainment Hack

It’s been four weeks since hackers calling themselves Guardians of Peace began their cyberterrorism campaign against Sony Pictures Entertainment. In that time thousands of executive emails and other documents have been posted online, employees and their families were threatened, and unreleased films were stolen and made available for illegal download. The hackers then escalated this week to threatening 9/11-like attacks against movie theaters scheduled to show the Sony film “The Interview.” That fanned security fears nationwide and resulted in the four top U.S. theater chains pulling the film from their screens, ultimately driving Sony to cancel the film’s release.

Here’s a look at key developments in the hack:

Nov. 24: Workers at Sony Pictures Entertainment in Culver City, California log on to their computers to find a screen message saying they had been hacked by a group calling itself Guardians of Peace. Their network is crippled. Personal information, including emails, Social Security numbers and salary details for nearly 50,000 current and former Sony workers are leaked online. Screeners of unreleased movies, including “Annie,” are uploaded to the Internet and are quickly downloaded illegally.

Some speculate that North Korea is behind the attack as retaliation for the upcoming movie “The Interview,” the Seth Rogen and James Franco comedy that depicts an assassination attempt on North Korean leader Kim Jong Un. Over the summer, North Korea had warned that the film’s release would be an “act of war that we will never tolerate.” It said the U.S. will face “merciless” retaliation.

Dec. 1: The Federal Bureau of Investigation confirms that it is investigating the cyberattack but declines to comment on whether North Korea or another country is behind the attack.

Dec. 3: Some cybersecurity experts say they’ve found striking similarities between the code used in the hack of Sony Pictures Entertainment and attacks blamed on North Korea which targeted South Korean companies and government agencies last year.

Dec. 5: The FBI says it is investigating emails that were sent to some Sony Pictures employees threatening them and their families.

Dec. 7: North Korea denies that it is behind the attack, but the country also condemns “The Interview” and relishes the attack as possibly “a righteous deed of the supporters and sympathizers” of the North’s call for the world to turn out in a “just struggle” against U.S. imperialism.

Dec. 8: Sony Computer Entertainment says its online PlayStation store was inaccessible to users for a couple of hours. The company did not link the outage to the Sony Pictures hack.

Dec. 11: Hollywood producer Scott Rudin and Sony Pictures co-chairman Amy Pascal apologize for embarrassing private emails that were leaked. The two exchanged emails in which they made racially offensive jokes about President Barack Obama and Rudin made disparaging remarks about actress Angelina Jolie.

Dec. 13: Leaks appear to include an early version of the screenplay for the new James Bond movie “SPECTRE.” Producers at Britain’s EON productions say they are concerned that third parties who received the screenplay might seek to publish it, and warn the material is subject to copyright protection around the world.

Dec. 15: A lawyer representing Sony Pictures warns news organizations not to publish details of company files that were leaked, saying the studio could sue for damages or financial losses.

A lawsuit is filed by two former Sony Pictures in a California federal court, seeking class-action status on behalf of other current and former studio workers affected by the data breach. The suit alleges that emails and other information leaked by the hackers show that Sony’s information-technology department and its top lawyer believed its security system was vulnerable to attack, but that company did not act on those warnings. The plaintiffs ask for compensation for fixing credit reports, monitoring bank account and other costs as well as damages.

Dec. 16: The hackers release another trove of data files, this time 32,000 emails to and from Sony Entertainment CEO Michael Lynton. Along with what they call the first part of “a Christmas gift,” the group threatens violence reminiscent of the September 11th, 2001 terrorist attacks, targeting movie theaters that plan to show “The Interview.” It warns people who live near such theaters to leave home.

Carmike Cinemas is the first chain to announce it will not show “The Interview” at its 278 theaters across the country. Sony Pictures cancels the New York City premiere of the movie at the Landmark Sunshine in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, scheduled for Thursday Dec 18th.

A second lawsuit is filed by two other former Sony Pictures employees who say the studio did not do enough to prevent hackers from stealing social security numbers and other personal information about current and former workers. It also seeks class-action status.

Dec. 17: The top theater chains in the country, Regal Cinemas, AMC and Cinemark, pull the “The Interview,” forcing Sony to cancel the film’s Christmas Day release. Seemingly putting to rest any hope of a delayed theatrical release or a video-on-demand viewing, Sony announces it has “no further release plans for the film.”

“We are deeply saddened at this brazen effort to suppress the distribution of a movie, and in the process do damage to our company, our employees, and the American public,” the studio says in a statement. “We stand by our filmmakers and their right to free expression and are extremely disappointed by this outcome.”

Shortly thereafter, a U.S. official says federal investigators believe there is a link between the cyberattack and North Korea.

Stars, politicians and pundits light up Twitter and the air waves weighing in on Sony’s decision to capitulate. Many decry the move as setting a dangerous precedent in the war against hackers.

Dec. 18: The White House says evidence shows the hack against Sony Pictures was carried out by a “sophisticated actor” with “malicious intent.” But spokesman Josh Earnest declines to blame North Korea. Earnest says he doesn’t want to get ahead of investigations by the Justice Department and the FBI.

A third lawsuit seeking class-action status is filed against Sony Pictures. The suit filed by two other former Sony workers seeks damages and restitution for those affected by the breach, including $1,000 for each person whose medical information was stolen. One plaintiff claims Sony allowed her medical information to remain on its servers for too long; she left the company in 2009. The suit also alleges that Sony prioritized damage control over embarrassing details included in the emails of its top executives, rather than properly informing its current and former workers about the breach.

From The Associated Press. AP writers Raphael Satter in London and Ted Bridis and Matthew Pennington in Washington contributed to this story.