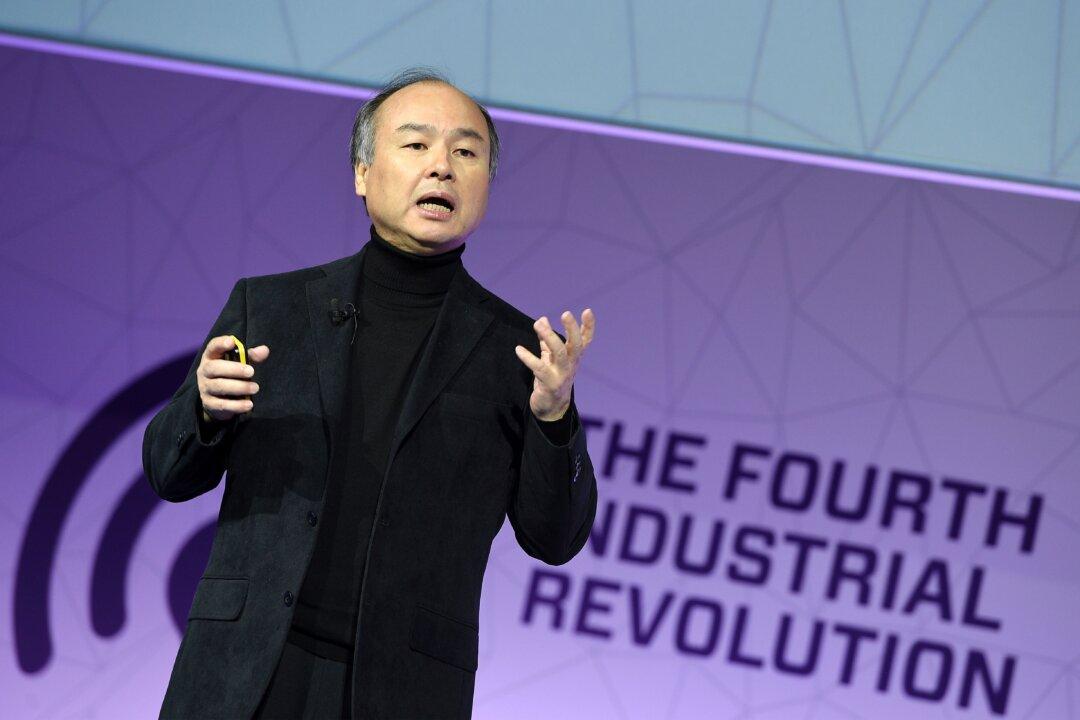

Masayoshi Son, the larger-than-life billionaire and chief executive of Japanese conglomerate SoftBank, doesn’t do anything small.

When Son announced in May that he’s raising $100 billion for a fund—dubbed the Vision Fund—to invest in technology companies, the investment community was taken aback. Is it a private-equity buyout fund? Is it a venture capital fund? What will it invest in?

The fund’s sheer size is staggering. In May, it closed on $93 billion in capital, and Son expects the fund to reach the $100 billion mark by end of the year. That dwarfs any private equity or venture capital (VC) fund ever raised in history.

Even its list of backers is impressive. Besides SoftBank, which is contributing $28 billion, investors include sovereigns Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates, corporations including Apple, Foxconn, and Qualcomm, and influential individuals such as Oracle founder Larry Ellison.

The drive to invest $100 billion in emerging technology comes from Son’s belief in the so-called computing singularity, or a point at which artificial intelligence will surpass human intelligence. “I totally believe this concept,” he said regarding singularity at the 2017 Mobile World Congress this year in Barcelona, according to TechCrunch. “If superintelligence goes inside the moving device, then the world, our lifestyle, dramatically changes.”

Son talked about the fund in awe-inspiring, if ambiguous, terms. Surpassing the typical scope of VC funds, the Vision Fund will “help build and grow businesses creating the foundational platforms of the next stage of the Information Revolution” by funding companies with “the potential to address the biggest challenges and risks facing humanity today,” Son announced at the fund’s first close.

Three months and a few deals later, SoftBank and Son’s vision and strategy are coming into focus. The size, scope, and unconventional investment style have the potential to disrupt the technology and VC industry for years to come.

Working With WeWork

On Aug. 24, Son executed a $4.4 billion deal with office space sharing startup WeWork.

SoftBank and Vision Fund’s complicated investment and joint-venture deal with WeWork provides a glimpse of how Son plans to deploy his massive war chest and augment his existing business.

The deal has two parts. Vision Fund is investing $3 billion to buy direct shares of WeWork, with a post-investment valuation of $20 billion, people close to the deal told the Financial Times on Aug. 25.

Separately, SoftBank itself is contributing another $1.4 billion to form a series of new joint ventures with WeWork to expand its office-sharing operations into China, Japan, and Southeast Asia.

WeWork has 214 buildings in 52 cities and leases temporary office space to established corporations and startups. It has its own list of qualified backers such as veteran VC fund Benchmark Capital.

The deal is unusual in the world of VC investing. Vision Fund’s $3 billion singular investment into one company is already one of the largest deals of the year, given that most VC funds don’t exceed $10 billion in total assets. In addition, SoftBank’s joint venture with WeWork to do business together is rare for a VC sponsor.

The Long View

At first glance, the WeWork deal is puzzling because it isn’t the type of business the Vision Fund is targeting—it’s not in robotics, automation, or artificial intelligence.

Neither is India’s leading e-commerce site, Flipkart. Vision Fund invested in Flipkart as part of a $1.4 billion financing round this summer. While the amount of the investment was not disclosed, the deal was the biggest ever private investment into an Indian technology startup.

Some of its other holdings do fit the artificial intelligence narrative. During the second quarter, SoftBank transferred its 4.9 percent stake in chipmaker and leading artificial-intelligence developer Nvidia Corp. to Vision Fund. The Financial Times reported that Vision Fund earlier this year bought a 25 percent stake in mobile chipmaker Arm Holdings, which had been acquired by SoftBank last year for more than $30 billion.

In July, Vision Fund led a $200 million Series B funding round into Plenty, a San Francisco-based agriculture technology startup. In the same month, it also invested $112 million into Brain Corp., a San Diego-based startup focused on self-driving technologies.

In assembling an eclectic portfolio of assets under the Vision Fund, Son could be building the 21st-century version of a keiretsu, a group of companies with interlocking ownership and business interests.

“[Masayoshi Son] just wants to do bigger, bolder things. He looks at a 300-year vision, or a 50-year vision. He doesn’t do things with a three-month, six-month, or nine-month process,” former SoftBank President Nikesh Arora told Bloomberg.

“He’s out there busy sowing the seeds for creating this cohesive information revolution.”

The exact time when the so-called information revolution, or singularity, would arrive is unknown. But SoftBank is accumulating a diverse mix of companies embracing such a change. If the future is data-driven, then there need to be systems to process data, and artificial intelligence to act upon data, as well as governance tools to control and guide such intelligence.