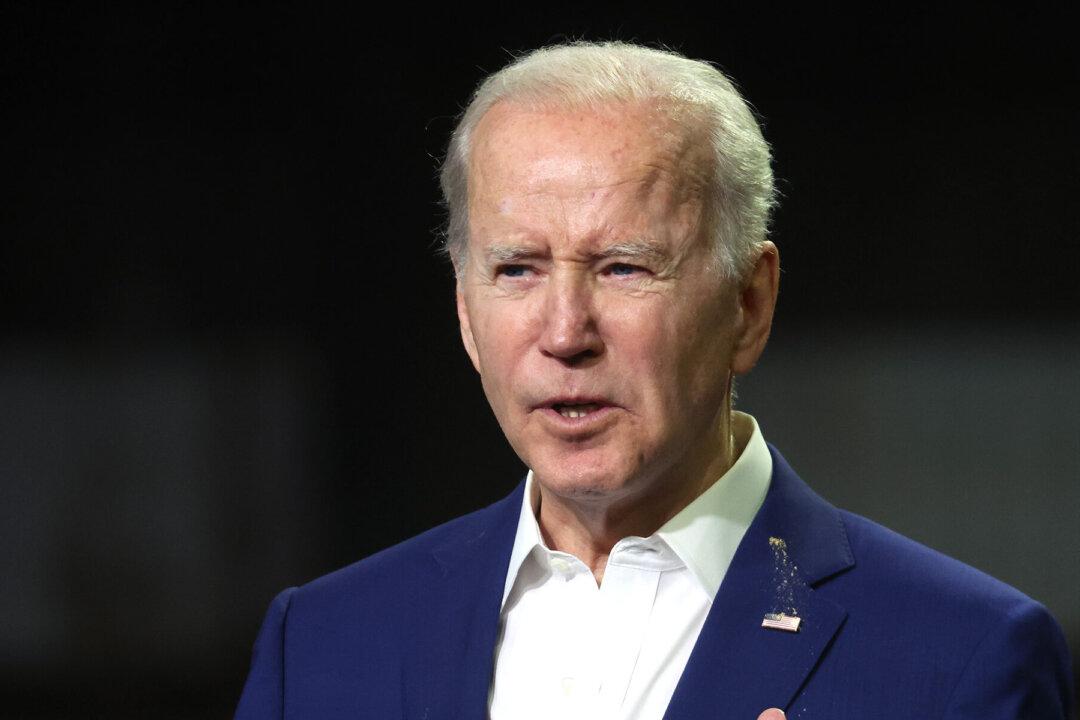

A recent poll finding that only 38 percent of Americans approve of the job that President Joe Biden is doing—down from 41 percent in December and 48 percent in July— is only the latest in a stream of bad news for the Democratic Party as November’s midterm elections draw near.

The 53 percent of Americans in the CNBC poll who said they disapproved cited Biden’s handling of the economy, along with the Ukraine crisis, as the primary reason.