Astronomers have discovered a giant swirling disk of gas 10 billion light-years away—a galaxy-in-the-making that is actively being fed cool primordial gas tracing back to the Big Bang.

Using the Cosmic Web Imager (CWI) at Palomar Observatory, the researchers were able to image the protogalaxy. They find that it’s connected to a filament of the intergalactic medium, the cosmic web made of diffuse gas that crisscrosses between galaxies and extends throughout the universe.

The finding provides the strongest observational support yet for what is known as the cold-flow model of galaxy formation. That model holds that in the early universe, relatively cool gas funneled down from the cosmic web directly into galaxies, fueling rapid star formation.

A paper describing the finding and how the CWI made it possible appears online in Nature.

The ‘Smoking Gun’

“This is the first smoking-gun evidence for how galaxies form,” says Christopher Martin, professor of physics at Caltech, principal investigator on CWI, and lead author of the new paper. “Even as simulations and theoretical work have increasingly stressed the importance of cold flows, observational evidence of their role in galaxy formation has been lacking.”

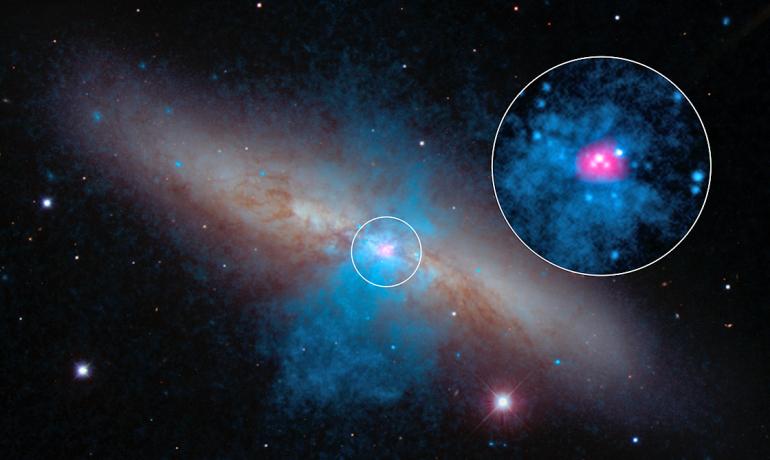

The protogalactic disk the team has identified is about 400,000 light-years across—about four times larger in diameter than our Milky Way. It is situated in a system dominated by two quasars, the closest of which, UM287, is positioned so that its emission is beamed like a flashlight, helping to illuminate the cosmic web filament feeding gas into the spiraling protogalaxy.

Last year, Sebastiano Cantalupo, then of University of California, Santa Cruz (now of ETH Zurich) and his colleagues published a paper, also in Nature, announcing the discovery of what they thought was a large filament next to UM287. The feature they observed was brighter than it should have been if indeed it was only a filament. It seemed that there must be something else there.