A 19-year Smithsonian study of wetland plants and carbon dioxide offers new hope about the planet’s resilience.

When carbon dioxide levels rise, wetland plants absorb much more carbon than when levels are low, according to a study published in the journal Global Change Biology from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center in Edgewater, Md.

The study’s findings suggest that wetlands will protect the earth from global warming—a runaway phenomenon, as projected by some studies.

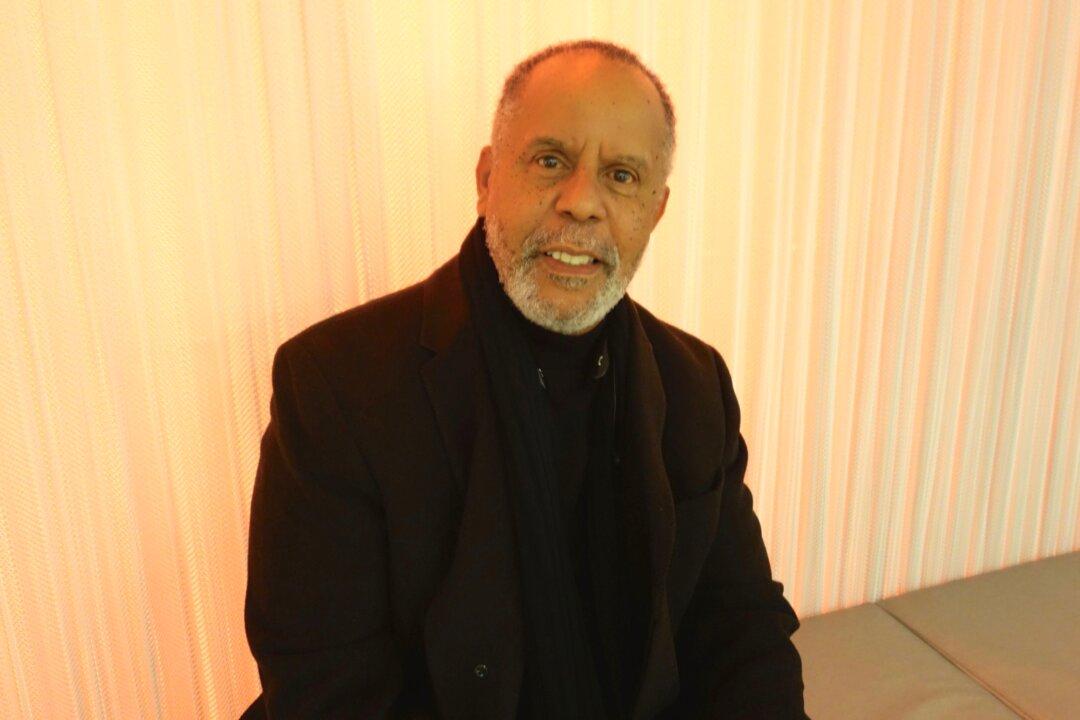

Plant physiologist Bert Drake created the Smithsonian’s Global Change Research Wetland in 1987 in Edgewater, at a time when scientists did not know how much carbon wetlands might absorb as the amount of carbon dioxide (C02) in the atmosphere increases.

Drake built open-top Mylar chambers—manmade domelike structures that contain a controlled environment—around marsh plots. Researchers kept half of them open to the natural atmosphere while the other half had extra C02 pumped in—up to 700 parts per million (ppm)—nearly doubling the CO2 levels of 1987 and simulating a future world. Drake and his colleagues measured how much CO2 went into the chambers and how much came out, and they were surprised to learn that different kinds of wetland plants capture from 13 to 32 percent more C02 when the atmosphere itself has more C02.

“The results of this study suggest that wetland ecosystems will assimilate more carbon as atmospheric CO2 levels continue to rise beyond the level of 400 ppm reached in May 2013,” said Drake in a press release.

The researchers found that drought, on the other hand, crippled the plants’ ability to take up carbon—absorption works only when the wetlands are intact.

So in the climate change equation, drought is a potential wild card. Wetlands can ameliorate some of the worst effects of rising C02 levels, yet without enough rainfall, their value as buffers and filters could be lost.