Organizations today operate in a world of uncertainty and rapid change, and weighty, new challenges that managers need to tackle are ever present and evolving. But the good news is that much great wisdom can be derived from lessons in history, and one rich source is ancient Chinese wisdom.

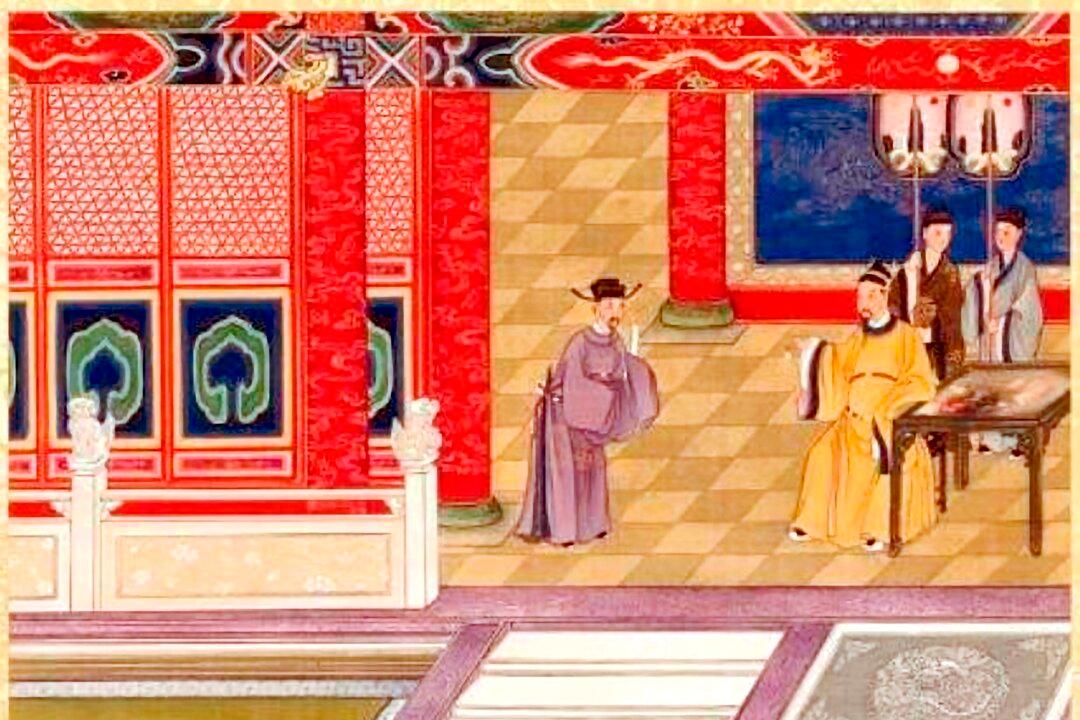

For example, in the “Analects of Confucius,” the first chapter lays out timeless advice on the subject of learning, and the fifth verse speaks to governance.

Confucius, who lived some 2,500 years ago, said: “To govern a large country, handle affairs in a prudent and serious manner and always be sincere, honest, and trustworthy.

“Be frugal in managing finances (save and don’t be wasteful), and love and care for the people. Let the people’s needs guide the proper timing for utilizing their labor.”