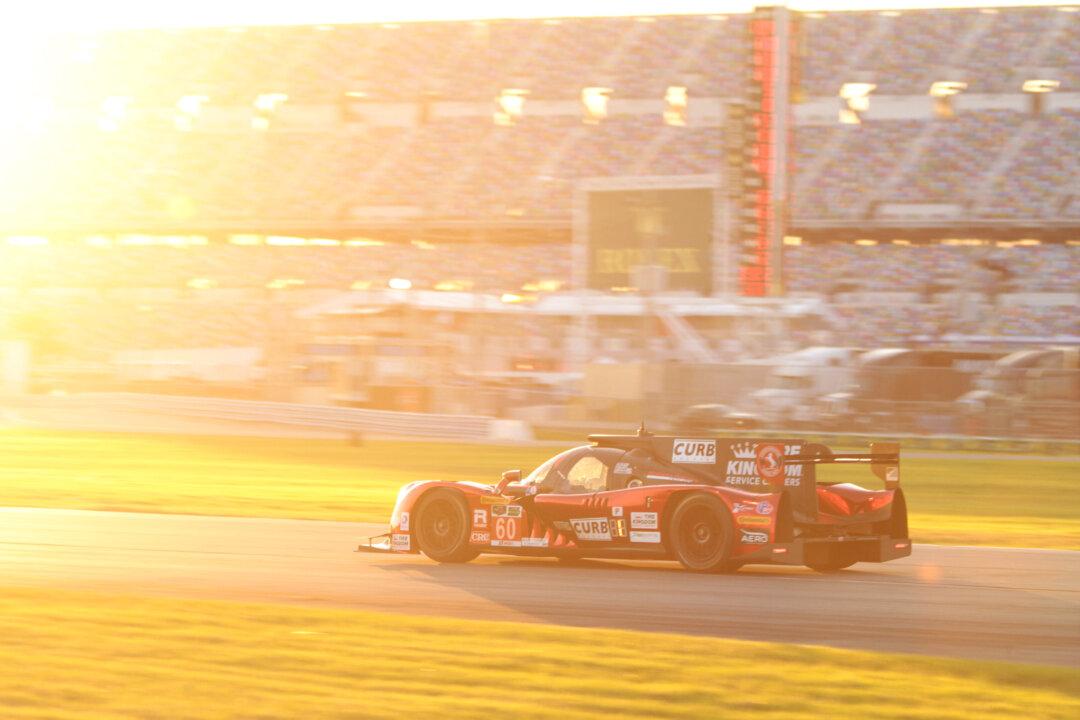

DAYTONA BEACH, Fla.—Qualifying for the Tudor United SportsCar Championship 2015 season-opening Rolex 24 at Daytona is done; the grid is set. Leading the 53-car field into the first turn will be the car which was quickest in every session, the #60 Michael Shank Racing Ligier-Honda, a car brand-new to the 2012 Rolex-winning team.

The Ligier-Honda is a P2 chassis being run by a team which had raced a Daytona Prototype for a decade, and which won the Rolex in a Riley-BMW DP.

MSR driver Oz Negri won the pole with a lap of 1:39.194 at 129.201, a full tenth of a second and four-tenths of a mile per hour faster than the next two cars, the Ganassi Racing Riley-Ford EcoBoosts. Fourth was defending Rolex champion (and 2014 Tudor Championship-winning ) #5 Action Express Racing Coyote-Corvette. Fifth was the much improved #0 DeltaWing Racing DWC13—a P2, the one-off DeltaWing, and three Daytona Prototypes in the top five.

None of these cars has any significant advantage over one another—or over the rest of the class. The first ten prototypes qualified within 1.14 seconds of Negri in the #60.

Why It Matters

For 15 years North American sports car racing was divided into two warring camps. Two new sanctioning bodies, Grand America and IMSA, presented their visions of the right way to run a successful series, each doing more to hurt the other than to demonstrate the superiority of either particular view.

On one hand, the American Le mans Series offered classes of cars based closely on the cars which ran at Le Mans (hence the name.) Relying on the Europea-based Federation Internationale de l‘Automobile and the Automobile Club de l’Oueste (FIA and ACO) ALMs fielded cars which frequently crossed the pond to race at Le Mans, the ultimate badge of credibility for many sports car fans.

The FIA/ACO cars were usually cutting-edge in design and construction; this, plus annual regulations updates, made the cars expensive to operate.

However much the teams had to spend on these cars, the fans loved them—the thrill of seeing the fastest, most advanced sports cars in the world racing at their home tracks brought fans to ALMS in (relative) droves. “The Cars are the Stars” perfectly sums up the appeal of ALMS (though harking back to 75 years of sports car history and racing at some classic North American tracks didn’t hurt.)

Unfortunately, there just aren’t a whole lot of sports car fans out there, and the ALMS business model proved unsustainable. Teams couldn’t make a living racing the complicated, difficult-to repair, often-changing cars, and eventually the series found itself in serious financial trouble.

The other team was the Grand American Rolex Sports Car Series, which was funded by and eventually purchased by NASCAR. The Rolex series started with a philosophy based on simple, tough, low-cost cars which could be easily repaired and which didn’t change from race to race—or from season to season.

Rolex Series management assumed that there were plenty of sports fans who would watch ports car racing if they could find an emotional hook—as in, make stars of the drivers, NASCAR had had huge success racing slow, heavy, primitive cars that bumped and banged all race long, and by making the drivers household names, attracted a fan base from well beyond the somewhat limited pool of race fans.

The Rolex Series rejected the “Foreign” rulesmakers, deciding that Americans did things differently. In 2003, the series introduced the Daytona Prototype, a chassis style which (with only minor upgrades) is still in use today.

Instead of drivers being penalized for “avoidable contact,” a little leaning and pushing was encouraged. NASCAR fans have told pollsters that restarts are the best part of the races (which occasionally led to “phantom yellows,” caution periods called for “debris on track” which no one could actually see). Similarly Rolex Series races always seemed to have a caution period in the final few minutes of the race, bunching up the field for a madcap “dash to glory” finish.

Operating costs in the Rolex Series were marginally lower. Cars lasted longer and were cheaper to fix. However, much of the cost of a racing are the fixed costs of transport and lodging, fuel and tires, which couldn’t be lowered. Further, many sports car fans rejected the slow, simple cars and the physical racing, which meant the Rolex Series had lower operating costs but also lower revenues.

Even with NASCAR money to back it, eventually the series found itself in serious financial trouble.

Tudor Series: New ‘Golden Age’ or ‘Rolex 2.0’?

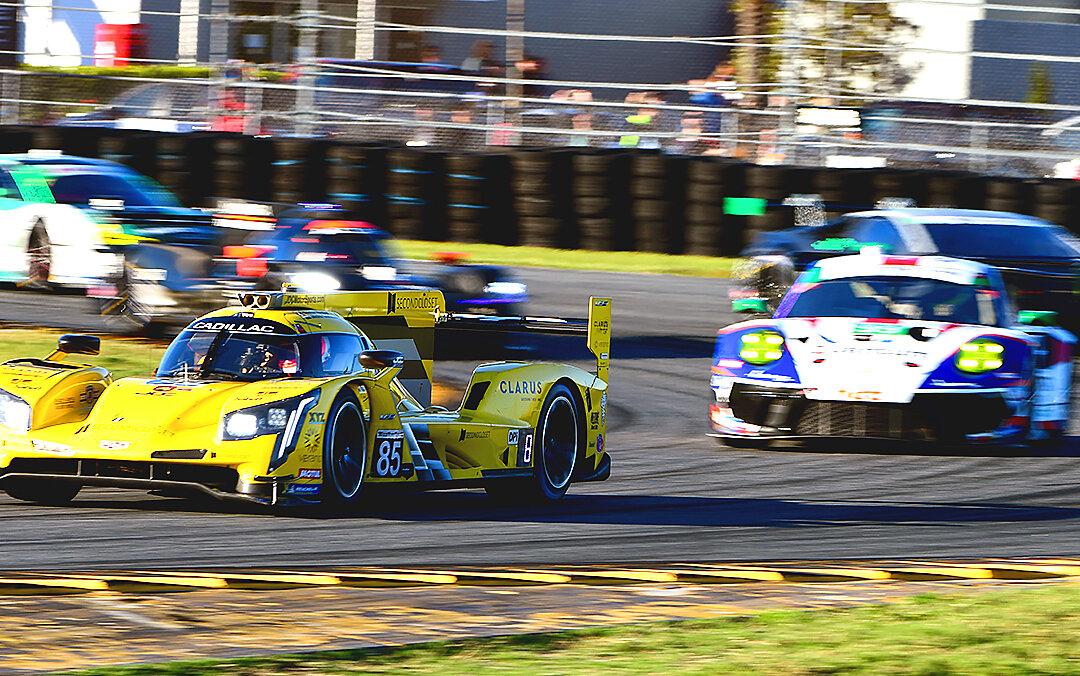

Finally in September 2013, NASCAR bought out the American Le Mans Series, merged it with the Rolex Series, and created the Tudor United SportsCar Series. When this series hit the track in 2014, a lot of fans assumed it would be “Rolex 2.0,” and the balance between the Rolex Daytona Prototypes and ALMS P2 cars made it seem that that would be the case.

The DPs won nine of 11 races.

The DPs all had to be updated to compete with the much faster P2s. After the upgrades, the DPs were heavier, but had much more power (about 100 hp at least) and a lot more torque, which meant they were quicker out of the corners and quicker down the straights.

On top of that, the DPs used tires made specifically for Daytona Prototypes—and so did the P2s, which meant the tires didn’t suit them at all.

The kind of physical racing which marked the Rolex Series often cropped up in the Tudor Championship—and the sturdier, heavier DPs usually got the best of it.

Daytona Prototypes won nine of 11 races in 2014—and a lot of fans weren’t happy. Vice President of Competition Scot Elkins had an almost impossible job, trying to balance two radically different types of cars which each made speed in different ways, but he never quit—even after the season ended.

Elkins gave his all—literally, as he left the series the day before the 2015 season started. What he left behind, though, was as nearly perfect a balance as could be hoped for (at Daytona, at least.) For the first time in a dozen years, an FIA-style high-downforce prototype took the pole for the Rolex 24.

‘United’ at Long Last

Does this mean the Shank car will win? Of course not—the race is 24 hours long, and a Lot of things can happen. Further, the field is so close, any of the top six or eight cars have a solid chance.

What this P2 pole does mean, is that ALMS fans—which outnumber Rolex fans about three-to-one (with about ten percent overlap, according to one poll) no longer need feel marginalized, no longer need to feel second-class. There was much discussion trackside about Shank Racing’s triumph, and more enthusiasm than this reporter had heard since the last ALMS race of 2013.

Regardless of whether a P2 or DP wins at Daytona—or Sebring, or Laguna Seca, or Mosport or Watkins Glen—if Tudor can maintain parity between the two chassis types the series gains a huge amount of credibility with the fans, many of whom were on the fence about following the series after 2014.

Shank Racing’s success at Daytona helps purge any resentment lingering from 2014—it gives the Tudor Championship a fair chance to win fans with what happens on track in 2015, rather than having to compensate for 2014 this year.

For the first time, the Tudor United Sportscar Championship fanbase is united.

Sure, if a DP wins the Rolex there will be a few naysayers who will claim it was all fixed, just a set-up stunt to get TV viewership up. They will be wrong, and they are not important.

What is important is that fans trackside (and some online) are excited about the Rolex 24 for the first time in a long time—in fact, fans are starting to be hopeful for the upcoming season.

The Tudor United SportsCar Championship got a huge gift from Michael Shank Racing. Let us hope the series appreciates it, and makes the best possible use of it.