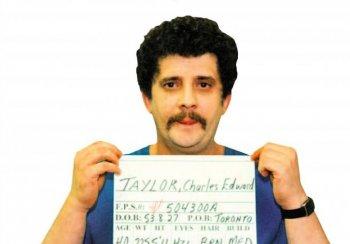

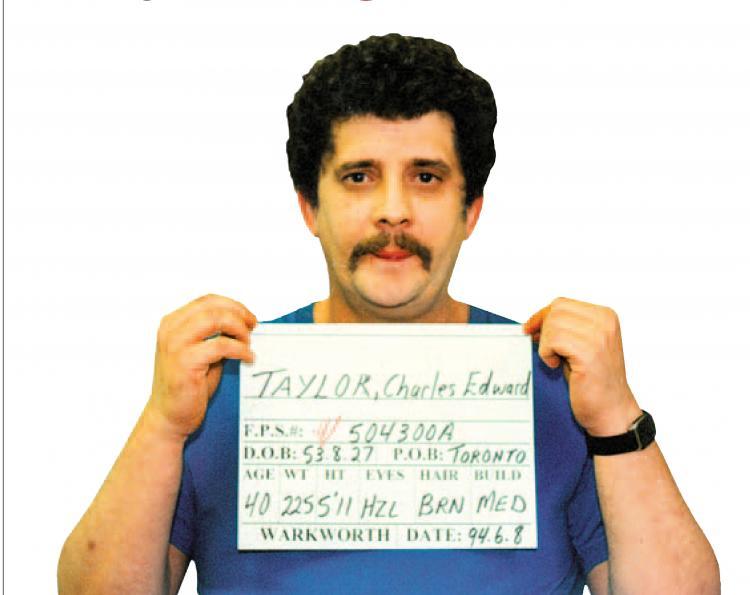

After Charlie Taylor was released from a federal penitentiary in 1994 the reaction from his home community of Hamilton was swift. There were angry calls for political intervention, picketing, heightened media attention, and 24-hour police surveillance.

Taylor was a high-risk pedophile who had just finished a seven-year sentence for sexual crimes against children—his fourth stint in jail for such offences. He was mentally disabled with no means of support and the people of Hamilton did not want Taylor around their children.

“Could you put him on a Mennonite farm?” Bill Palmer, a prison psychologist asked Harry Nigh, a Mennonite minister and Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) community chaplain who already knew Taylor.

The farm idea didn’t work out, but Rev. Nigh gathered a group of volunteers, mostly Mennonite congregants, who set up a “circle” of support for Taylor to integrate him into the community while holding him accountable.

“We had no intention of it being a project or a program. Actually, if I’d had any idea of what was going to happen, at least in that immediate short-term, I probably would have found a way to duck out of it,” says Nigh, referring to the seemingly insurmountable problems that cropped up initially.

Three months later Wray Budreo, one of Canada’s most notorious pedophiles who had been in and out of prison for 30 years for sexually assaulting young boys, was released in Toronto.

Amidst another public outcry, a group of volunteers there organized a second circle with the same parameters, and Circles of Support and Accountability (COSA), sponsored in part by Correctional Services, was up and running.

“There was the realization that maybe something was happening that we could give that could be a source of hope to other communities, because people just get paralyzed around this stuff,” says Nigh.

With a mantra of “No More Victims,” the main goal of COSA is to reduce the risk of future sexual crimes by assisting and supporting released offenders who are often shunned by their friends and family out of fear.

COSAs work closely with the police, and if the core member reoffends the police are notified immediately.

At the outset Rev. Nigh was sure that, like most pedophiles, it would be only a matter of time before Charlie Taylor reoffended. But Taylor died in 2006—12 years after his circle was formed—without ever committing another sex crime. Likewise Budreo, who died 14 years after his release.

Indeed, COSAs have been shown to have a positive impact on recidivism rates. A study by CSC compared a group of 60 high-risk sex offenders involved in COSA with 60 who had been released at the end of their sentence but who had not been part of a support circle.

The results showed that offenders who participated in COSAs had a 70 percent reduction in sexual recidivism compared to the non-COSA group. There was also a large reduction in violent recidivism in the COSA group.

For those in the COSA group who did reoffend sexually, the study found that the offenses were categorically less severe than prior offenses. This was not observed in the matched comparison group.

It was an innovative response to a complicated situation, and it caught on. Today, this uniquely Canadian initiative has been implemented across Canada, in several U.S. states, and in Britain’s Thames Valley region. Countries including the Netherlands, Bermuda, and South Africa are also showing interest.

“We all work best when we are supported and held accountable,” says Eileen Henderson, the Restorative Justice Coordinator for Mennonite Central Committee Ontario who has worked with the Ontario COSA project for 10 years.

Typically, about five volunteers enter into an agreement with a newly released sex offender, called a “core member.” At least one volunteer meets with the core member on a daily basis for the first 60 to 90 days, while the others have weekly contact, and the full circle meets on a weekly basis. However, the circle’s involvement with the core member continues long term.

The sex offender, who is helped with such things as finding housing, securing a stable income, and attending medical appointments, pledges to abide by any conditions imposed by the court and to communicate openly with circle members.

“It’s an environment where they can be open and honest about their past and what they’re thinking and feeling, at the same time knowing that there is acceptance, there’s support, but also accountability factored in,” Henderson says.

The relationship that develops between the sex offender and the other circle members is all-important, she says, as it strengthens the offender’s commitment to being accountable.

“That’s our only real tie with the men that we walk with.... Accountability is all about the value of the relationship and the desire to move forward.”

As for core members, the CSC study found that they reported feeling less nervous, afraid, and angry as a result of their experience in a COSA. They also reported that they were more realistic in their perspectives, more confident, felt more accepted, and experienced pride for not reoffending.

“It’s not that easy to get a sex offender to stop doing what they have been doing,” says Robert Gordon, director of criminology at Simon Fraser University.

“So rather than having these folks locked up in perpetuity or at least until they’re way past the point when they don’t have any interest, [COSA] is a solution for communities, and especially for those communities who rightly have great concerns about discharged sex offenders living in their midst.”

COSA’s weakness, says Gordon, is that it depends on volunteers, which sometimes raises recruitment challenges. “But fortunately there appears to be an army of interested people coming from the faith communities.”

In the process evaluation for the CSC study, the majority of COSA volunteers said they were motivated by a “need to be involved” in their community, and more than three-quarters felt a sense of teamwork in their circles work.

It gets into your soul I think,” says Henderson. “It’s just a very powerful community.”

Taylor was a high-risk pedophile who had just finished a seven-year sentence for sexual crimes against children—his fourth stint in jail for such offences. He was mentally disabled with no means of support and the people of Hamilton did not want Taylor around their children.

“Could you put him on a Mennonite farm?” Bill Palmer, a prison psychologist asked Harry Nigh, a Mennonite minister and Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) community chaplain who already knew Taylor.

The farm idea didn’t work out, but Rev. Nigh gathered a group of volunteers, mostly Mennonite congregants, who set up a “circle” of support for Taylor to integrate him into the community while holding him accountable.

“We had no intention of it being a project or a program. Actually, if I’d had any idea of what was going to happen, at least in that immediate short-term, I probably would have found a way to duck out of it,” says Nigh, referring to the seemingly insurmountable problems that cropped up initially.

Three months later Wray Budreo, one of Canada’s most notorious pedophiles who had been in and out of prison for 30 years for sexually assaulting young boys, was released in Toronto.

Amidst another public outcry, a group of volunteers there organized a second circle with the same parameters, and Circles of Support and Accountability (COSA), sponsored in part by Correctional Services, was up and running.

“There was the realization that maybe something was happening that we could give that could be a source of hope to other communities, because people just get paralyzed around this stuff,” says Nigh.

With a mantra of “No More Victims,” the main goal of COSA is to reduce the risk of future sexual crimes by assisting and supporting released offenders who are often shunned by their friends and family out of fear.

COSAs work closely with the police, and if the core member reoffends the police are notified immediately.

At the outset Rev. Nigh was sure that, like most pedophiles, it would be only a matter of time before Charlie Taylor reoffended. But Taylor died in 2006—12 years after his circle was formed—without ever committing another sex crime. Likewise Budreo, who died 14 years after his release.

Indeed, COSAs have been shown to have a positive impact on recidivism rates. A study by CSC compared a group of 60 high-risk sex offenders involved in COSA with 60 who had been released at the end of their sentence but who had not been part of a support circle.

The results showed that offenders who participated in COSAs had a 70 percent reduction in sexual recidivism compared to the non-COSA group. There was also a large reduction in violent recidivism in the COSA group.

For those in the COSA group who did reoffend sexually, the study found that the offenses were categorically less severe than prior offenses. This was not observed in the matched comparison group.

It was an innovative response to a complicated situation, and it caught on. Today, this uniquely Canadian initiative has been implemented across Canada, in several U.S. states, and in Britain’s Thames Valley region. Countries including the Netherlands, Bermuda, and South Africa are also showing interest.

“We all work best when we are supported and held accountable,” says Eileen Henderson, the Restorative Justice Coordinator for Mennonite Central Committee Ontario who has worked with the Ontario COSA project for 10 years.

Typically, about five volunteers enter into an agreement with a newly released sex offender, called a “core member.” At least one volunteer meets with the core member on a daily basis for the first 60 to 90 days, while the others have weekly contact, and the full circle meets on a weekly basis. However, the circle’s involvement with the core member continues long term.

The sex offender, who is helped with such things as finding housing, securing a stable income, and attending medical appointments, pledges to abide by any conditions imposed by the court and to communicate openly with circle members.

“It’s an environment where they can be open and honest about their past and what they’re thinking and feeling, at the same time knowing that there is acceptance, there’s support, but also accountability factored in,” Henderson says.

The relationship that develops between the sex offender and the other circle members is all-important, she says, as it strengthens the offender’s commitment to being accountable.

“That’s our only real tie with the men that we walk with.... Accountability is all about the value of the relationship and the desire to move forward.”

As for core members, the CSC study found that they reported feeling less nervous, afraid, and angry as a result of their experience in a COSA. They also reported that they were more realistic in their perspectives, more confident, felt more accepted, and experienced pride for not reoffending.

“It’s not that easy to get a sex offender to stop doing what they have been doing,” says Robert Gordon, director of criminology at Simon Fraser University.

“So rather than having these folks locked up in perpetuity or at least until they’re way past the point when they don’t have any interest, [COSA] is a solution for communities, and especially for those communities who rightly have great concerns about discharged sex offenders living in their midst.”

COSA’s weakness, says Gordon, is that it depends on volunteers, which sometimes raises recruitment challenges. “But fortunately there appears to be an army of interested people coming from the faith communities.”

In the process evaluation for the CSC study, the majority of COSA volunteers said they were motivated by a “need to be involved” in their community, and more than three-quarters felt a sense of teamwork in their circles work.

It gets into your soul I think,” says Henderson. “It’s just a very powerful community.”