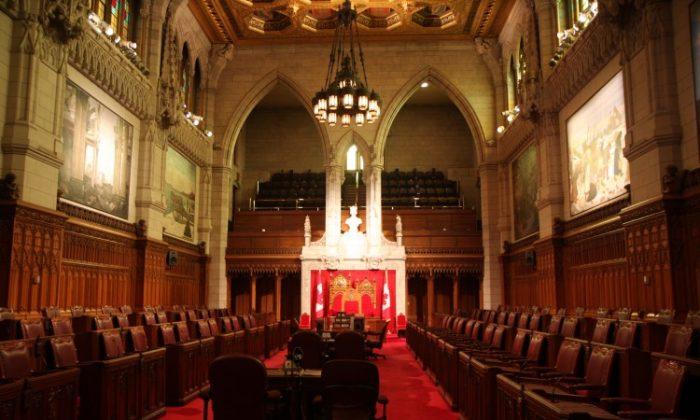

PARLIAMENT HILL, Ottawa—Parliament is exploring the thorny issue of Senate reform, a process the government hopes can enrich Canadian democracy if it doesn’t get caught on any number of hooks along the way.

The NDP says the changes are ineffective and the Senate should be abolished, a position supported by two of Canada’s foremost political scientists. The government argues the reforms advance its long-term commitment to make the Senate more democratic and accountable.

There is speculation Prime Minister Stephen Harper could eventually move to abolish the Senate if the reforms don’t pass, but PMO spokesperson Sara MacIntyre could not confirm that position and said the focus is on passing the reforms.

“We are committed to moving that forward,” she said. “Right now we are on a path to reforming the Senate.”

But after Immigration Minister Jason Kenney said on CTV’s Power Play last week that if the reforms fail the government is “prepared to entertain a more dramatic option,” the rumour that the Senate could be soon a thing of the past has spread.

It is substantiated in part by the PM’s own comments to the Australian Parliament in 2007. Australia’s upper chamber is elected.

“Australia’s Senate shows how a reformed upper house can function in our parliamentary system. And Canadians understand that our Senate, as it stands today, must either change or, like the old upper houses of our provinces, vanish,” he said.

Senate Reforms

The Conservatives tabled a two-part bill Tuesday that will limit Senators to single nine-year terms after being appointed based on non-binding provincial elections. The prime minister would still retain ultimate authority on appointees, but would be obligated to consider those election results.

NDP MP Pat Martin says the red chamber is little more than “an expensive nuisance.”

“They not only clutter up the place, the are always underfoot,” he said.

Martin wants to starve the Senate of funds and tabled a motion to exclude some $59 million for the Senate from the current budget to be debated separately.

While Nova Scotia and Ontario have joined the NDP’s call to abolish the Senate, such a move would require the support of seven provinces containing half of Canada’s population.

The government bill tries to side-step that constitutional requirement but even so, Nelson Wiseman, an associate professor of political science at the University of Toronto, believes court challenges are inevitable. Quebec has already promised to do just that.

Wiseman thinks Harper may be on firmer ground with the term limits, but the proposed elections could be construed as an indirect attempt to change the constitution and are likely to be challenged.

But that is just the beginning, he said. “There will always be unintended consequences.”

Problems of an Elected Senate

Chief among those consequences is the concern that an elected Senate will start rejecting legislation passed by the House of Commons.

Since 1997, the Senate has only rejected four bills, but that could increase if elected senators believe the public has given them a mandate to act more assertively. Theoretically, a senator who campaigned on certain issues would be obliged to follow through on those positions rather than defer to will of MPs and rubber stamp their bills.

“Why should he defer if he was elected?” asks Wiseman

Wiseman isn’t alone in saying the changes are problematic and that abolishing the Senate is a better option. Political scientist and Queen’s University professor emeritus Ned Franks agrees.

Franks says elected senators will compete with MPs in the House and with provincial parliamentarians for speaking as the legitimate voice of constituents. But unlike MPs and provincial representatives, senators would be elected by the entire province rather than a specific region, which broadens their claim to legitimacy even further.

Franks is also concerned that a two-term prime minister could conceivably appoint the vast majority of senators once all become subject to nine-year terms. Under the bill, senators appointed after October 2008 would face elections, while those appointed before would sit until their mandatory retirement at 75.

He believes elections could push the Senate in the wrong direction, making the red chamber more partisan. He is also worried about what could be lost, he says.

“The Senate does a lot of good work that is not appreciated.”

Specifically, senators’ long terms move them beyond partisan issues of the day and give them ample time to study complicated issues, producing some of Parliament’s best reports.

However, if it came down to a choice between the reforms and no Senate at all, Franks would abolish it.

But there is another route, he says—a modified appointment process. A panel made up of various people, including the Governor General, provincial Lieutenant Generals, Chief Justices, or Companions of the Order of Canada could appoint senators instead of the prime minister.

This would remove the problem of parties appointing their supporters or favourite campaign managers to the Senate while not granting senators additional authority.

“I am not suggesting that is the right answer, but it is something you could consider,” Franks says.

He adds that there is no point in a Senate that just rubber stamps Parliament’s bills, but neither is it desirable to have a Senate that constantly opposes the will of Parliament.