In the decades after the Industrial Revolution, educational reformers led the effort to modernise schools and classroom spaces, and the ubiquitous one-room schoolhouse gradually gave way to bigger and more sophisticated designs. Scholars such as Lindsay Baker at the University of California, Berkeley have traced the subsequent history of these school designs, and have noted the surprising ebb and flow of attention to details such as indoor air quality and access to daylight.

This article explores some school designs from across these decades in the USA and Europe.

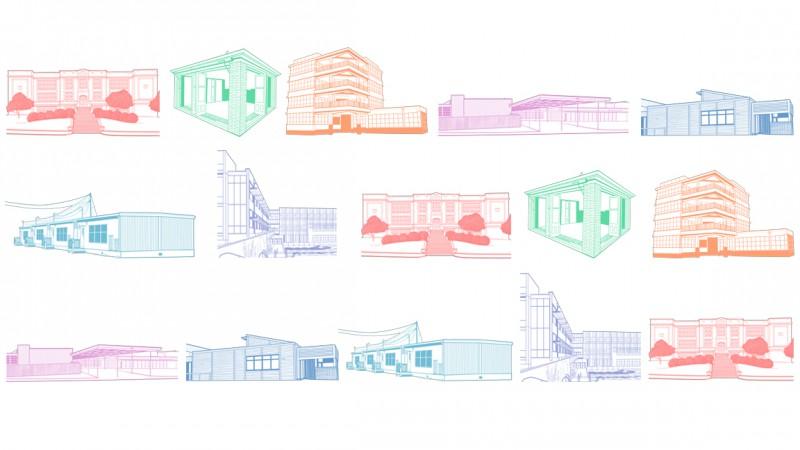

Wiley Elementary School, Raleigh, North Carolina, 1924. Phoebe Bell