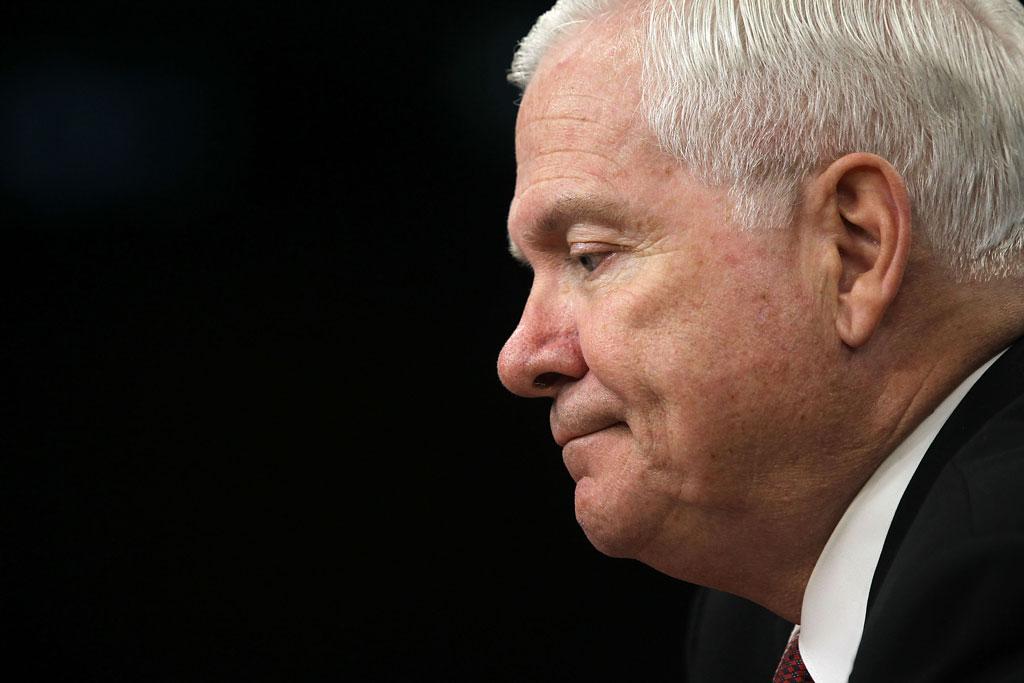

The New York Times recently ran a four-part post in its Opinionator section by filmmaker and blogger extraordinaire Errol Morris titled The Certainty of Donald Rumsfeld. Complete with interviews with those present, including Rumsfeld himself, about which Morris has just made a documentary titled The Unknown Known, it’s a meditation on what George W. Bush’s infamous first secretary of defense expounded on at a 2002 press conference about the lack of evidence that Iraq had a nuclear-weapons program.

Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

Which, common sense would seem to dictate, is what 99.9% of the universe is composed of, in relation to us anyway. Speaking of outer space, Morris quotes Rumsfeld’s memoir:

I first heard a variant of the phrase “known unknowns” in a discussion with former NASA administrator William R. Graham, when we served together on the Ballistic Missile Threat Commission in the late 1990s. Members of our bipartisan commission were concerned that some briefers from the U. S. intelligence community treated the fact that they lacked information about a possible activity to infer that the activity had not happened and would not. In other words, if something could not be proven to be true, then it could be assumed not to be true.

In case you hadn’t noticed, Rumsfeld, as amply documented by Morris, has had a long-standing problem with uncertainty and gray areas. Still on space, Morris interviewed the renowned British astronomer Martin Rees, who pointed out the banality of Rumsfeld’s observations.

ERROL MORRIS: … Presumably, the argument is, “Just because we can’t find any evidence that Saddam Hussein has weapons of mass destruction, that doesn’t mean hedoesn’t have weapons of mass destruction.”

MARTIN REES: I don’t regard that as profound. It’s a fairly obvious comment that is used in all kinds of different contexts.

ERROL MORRIS: And the known known and the known unknown?

MARTIN REES: This is not profound, either, but it’s an interesting distinction. Most people who write about risk and hazard would distinguish between risk and uncertainty.

ERROL MORRIS: Yes, but —

MARTIN REES: Risk is something where you can assign a probability. But as to what’s going to happen in 10 or 20 years, then you can’t really assign realistic probabilities. I suppose that’d be what you’d call an “unknown unknown.” Ultimately, I don’t think there’s anything special in the scientific method that goes beyond what a detective does.

Then Morris quotes Hans Blix, the executive chairman of the United Nations Monitoring, Verification, and Inspection Commission, from his book Disarming Iraq He turns Rumsfeld’s observations on their head.

Several countries, including the U.S., had given us a good number of sites for possible inspection, and at none of the many sites we actually inspected had we found any prohibited activity. The sites we had been given were supposedly the best that the various intelligence agencies could give. This shocked me. If this was the best, what was the rest? Well, I could not exclude the possibility that there was solid non-site related intelligence that was not shared with us, and which conclusively showed that Iraq still had weapons of mass destruction. But could there be 100-percent certainty about the existence of weapons of mass destruction but zero-percent knowledge about their location?

Or as Morris himself writes, “Absence of evidence could be evidence of absence or evidence of presence. Take your pick. An obscurantist’s dream.”

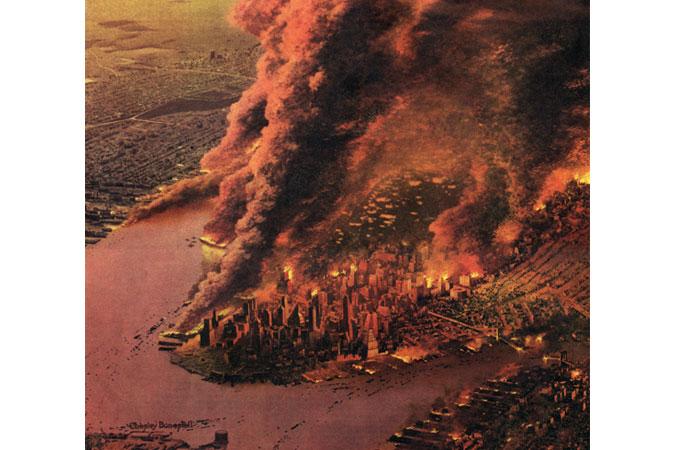

I would add that what Rumsfeld says about covering every possible threat paralleled comrade in arms Dick Cheney’s one percent doctrine, as author Ron Suskind called it. You know, the one that goes (in Cheney’s words): “If there’s a 1% chance that Pakistani scientists are helping al-Qaeda build or develop a nuclear weapon, we have to treat it as a certainty in terms of our response.”

Obviously the world can’t work like that or suspicious minds would rule the world. (Oh, that’s right, they do.)

Both Rumsfeld and Cheney might claim that they were leaving no stone unturned to protect the American people. But their over-reaction to their own fears, as projected onto the American people, were obviously symptoms of authoritarian personalities at their worst. Far from the benevolent patriarchs they no doubt characterized themselves as, Rumsfeld and Cheney were, if not paranoid, pathological in their attempts to foresee and control any fore- ― or unfore- ― seeable outcome.

Read the original article on the Foreign Policy in Focus website.