Researchers and U.S. health regulators are concerned that the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) virus may quickly develop resistance to new antiviral treatments from Pfizer and Merck, prompting scientists to find new combinations that better protect against the pathogen that causes COVID-19.

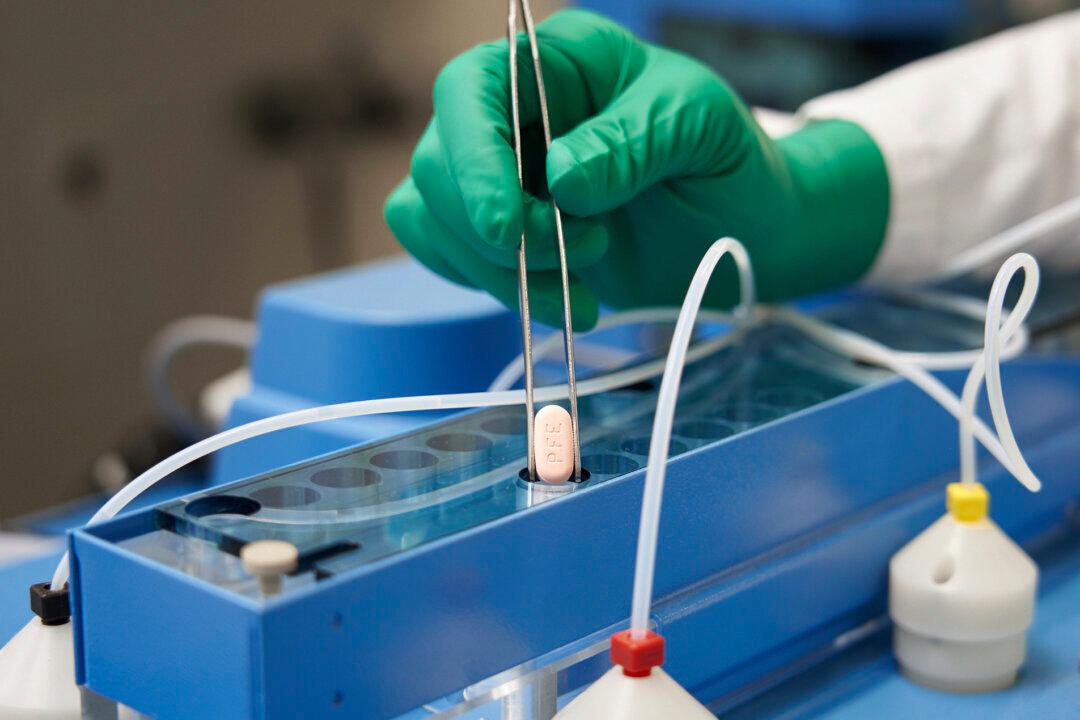

Molnupiravir, developed by Merck and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, is intended for home use by adults with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 who are at high risk of developing severe disease. The drug is taken orally in pill form, twice a day for five days, within five days of the onset of symptoms.