LONDON—Thomas Wolfe wrote “You Can’t Go Home Again” years ago, and its core truth keeps popping up in my life even as I tend to retrace some of my life journeys, in an endless walk down memory lane.

I am back in London, as cold and wet as I remember it, to attend an event honoring those of us at my mid 1960s alma mater, The London School of Economics and Political Science, who went to South Africa on underground missions. I was on the political side of the college’s split personality back in 1966–1968.

[topic] This event marked my real major in what the Rolling Stones called “street fighting years”: imagining world revolution.

Our group of solidarity stalwarts is now called the London Recruits. There is now a book, “London Recruits: The Secret War Against Apartheid,” out from Merlin Press telling our story in the words of many participants, including myself.

Yes, I was an activist in those pre-journalism years, blamed by some in the then-Fleet Street press for sparking the LSE’s student “troubles” that soon morphed into an occupation and dramatic student protest.

They dubbed me “Danny the Yank,” in the spirit of the French Press that labeled Dany Cohn-Bendit, a student activist in Paris who sparked a real revolution as “Dany le Rouge” (Danny the Red).

In the mid l960s the African National Congress (ANC) was all but smashed by the apartheid state. Mandela began his life sentence on Robben Island in 1964 along with his fellow leaders, all convicted of sabotage in the infamous Rivonia trial. They all expected to be hung and then to die there. He would not be released for 27 years.

Thousands more were later brutalized and rounded up. The resistance movement seemed crushed although top leaders like Oliver Tambo and Joe Slovo and many militants escaped into exile in Africa and London where they spent decades plotting their way back.

With their movement on the run, the ANC decided to recruit non-South Africans, mostly British Communists, Socialists, anti-apartheid activists, and this one American civil rights worker, to go on missions into South Africa to distribute flyers promoting the ANC, through the use of leaflet bombs to stir the local press and public.

I was one of the first to take part in this scary and desperate effort to keep the ANC visible at a low point in its 100-year history. This effort went on for five years while the ANC rebuilt its internal structures and armed wing, “Umkhonto wi Sizwe” (the Spear of the Nation.)

Later, some of these recruits got into weapons smuggling by setting up a safari company that could cross borders. Some 40 tons of weapons were moved that way, we were told at the event.

Two of my colleagues, unknown to me at the time because of secrecy and compartmentalization, were arrested and jailed. I was naive about the dangers.

At the Little Theater at the LSE where I held forth in many a fierce debate back in the day, there were moving stories from the recruits about their adventures and fears. Only a few had ever left their country. Some had never even flown in planes before.

Many were working class blokes of the left persuasion who signed on at the inspirational urging of Ronnie Kasrils, then a part of the underground and later South Africa’s outspoken minister of intelligence.

Kasrils spoke to his “alumni association” of once young recruits, his “army” of infiltrators, and preached the message of the value of international solidarity. This was an example of an initiative that worked.

He is now active on behalf of the Palestinian cause and increasingly critical of the current ANC leadership. He has certainly earned the right to speak out.

On one of my trips to South Africa, I visited him in his spy shop that featured pictures of Fidel Castro on the wall, and gifts from visiting intelligence chiefs including high-ups in the CIA and FBI that once tracked him. (His first book was called “Armed and Dangerous.”)

Unfortunately, the event was poorly promoted, some believe even sabotaged by the LSE’s current administration, which had been caught up in a scandal after it was revealed that the school took money from Gadhafi.

It is also possible that our gang of gray-haired old timers was just not aware that our event was scheduled on the last day of the term with many students eager to leave town. A nasty London-style rain shower and freezing weather were not exactly conducive to drawing a crowd.

One Palestinian student, 1 of 15 or more undergrads that came spoke up. Only 30 percent of the LSE student body is now from the U.K., probably because of unaffordable fees.

The student asked if we had ever feared that our gesture of support could backfire and hurt the very people we went to help, a query reflective of the cynicism of these times, and an implied critique of the “white man’s burden” that did so much to harm Africa in the guise of helping it develop.

Some of the recruits responded by reminding everyone they were invited. But others admitted that they too were initially wary, but went ahead anyway—and are now proud to have done so.

The two recruits who were jailed have since won medals from the South African government.

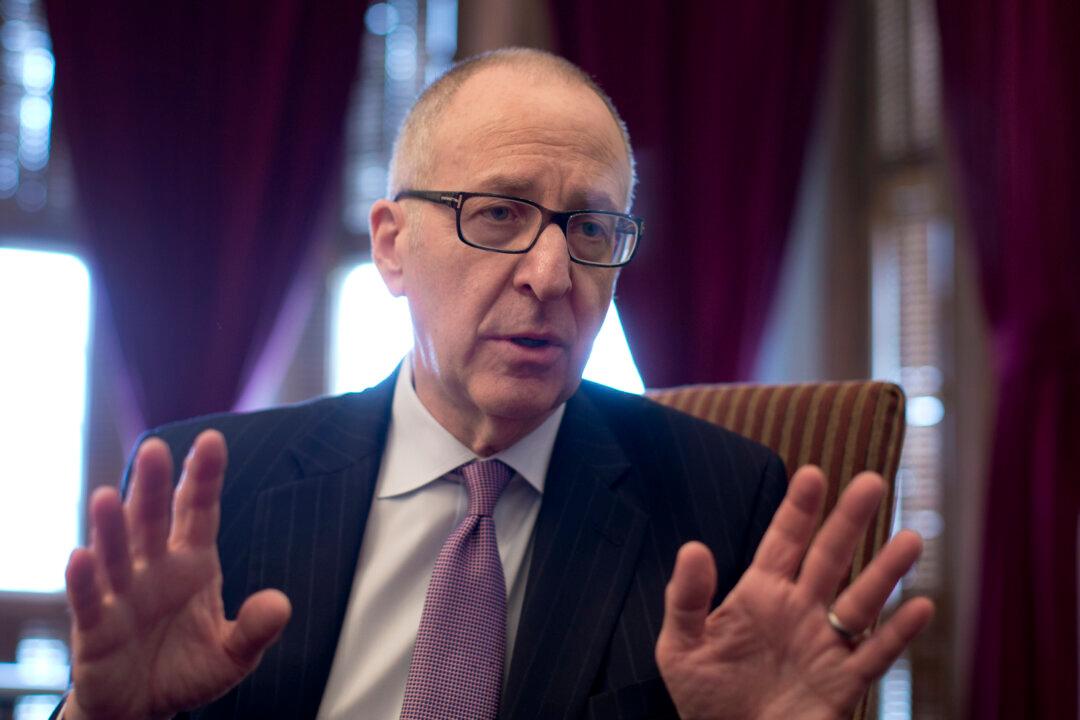

News Dissector Danny Schechter has continued to be engaged with South Africa. He produced the weekly South Africa Now TV series between 1989 and 1991, and helped produce the album Sun City: Artists Against Apartheid. He is finishing a five-hour TV series as a companion the forthcoming movie “Mandela: The Long Walk To Freedom,” due in theaters in December. Comments to [email protected].