HONG KONG—The Hong Kong University (HKU) Council has rejected the appointment of former law dean Johannes Chan to the post of pro-vice chancellor, although the HKU election committee recommended Chan for the position.

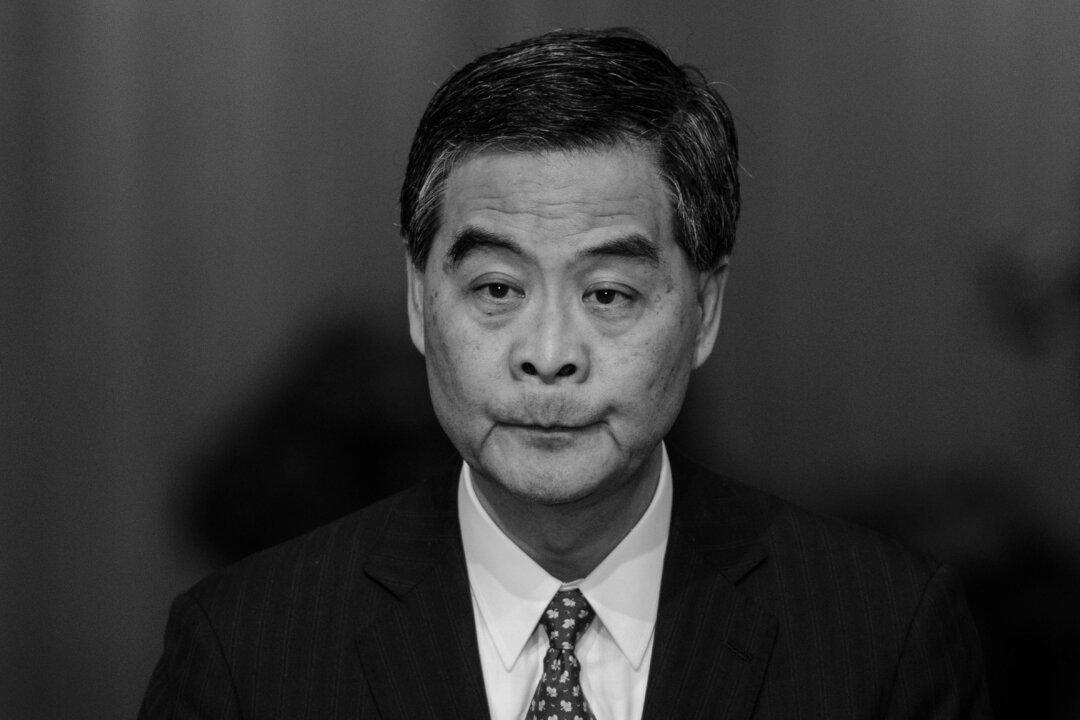

The council’s decision has caused an outcry, as many suspect that Hong Kong Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying interfered with Chan’s appointment for political reasons. The incident continues to simmer. About 2,000 black-clad HKU employees and students marched on campus to protest, and 60 scholars announced the establishment of a “Scholars’ Alliance of Academic Freedom.”

The Wall Street Journal published an article on Oct. 7 titled “Hong Kong University Purge: Pro-Beijing forces target a top school’s leaders to intimidate professors.”

The article stated that one year after the large-scale protests for democracy led by university students, the government is taking revenge against democracy supporters at HKU.

As a pro-democracy voice, Chan has faced a campaign of criticism for the past several months, and pro-Beijing newspapers have published hundreds of articles accusing him of “meddling in politics,” WSJ reported.

The council rejected his appointment by a 12-8 vote, according to WSJ.

Critics blamed Chan for mishandling a donation, although the governing council cleared him of wrongdoing earlier this year, the article stated.

The article alleged that the votes against Chan’s appointment came from politicians, business tycoons, and other external council members. Six of these members were appointed by Beijing supporter Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying, and seven are members of Chinese regime bodies such as the National People’s Congress, the article stated.

The article said that the oppression of academic freedom at HKU is part of a larger campaign against institutions that bring freedom and prosperity to Hong Kong, such as independent courts, uncensored media, and honest law enforcement.

Chan’s Response

Chan has repeatedly indicated his confusion over the lashing from pro-Communist media. A few days earlier, he published an article in a newspaper stating that some of the HKU Board Committee’s defamatory statements lacked facts and were irresponsible.

He also expressed his sadness over their harsh, biting remarks. He stated, “A closed-door meeting is for letting everyone share open views, but it does not mean you can recklessly lash out with unfounded defamatory statements.”

During an earlier interview, Chan mentioned that he had constantly contributed to mainland China over the last decade. “I do not know what I have done that Beijing felt was unacceptable,” he said.

Chan said he began to give lectures in mainland China before 1997, held seminars and conferences in the mainland starting in the 1990s, and introduced prestigious foreign universities to China.

Chan and HKU arranged student exchange programs with the mainland. For many years, HKU financially assisted many mainland Chinese students who came to Hong Kong for academic exchange.

During his 12 years as the dean of the faculty of law, Chan made a lot of exchanges with the mainland. Even now, Chan still holds common law training courses in the mainland.

He has trained hundreds of mainland officials and judges over the past many years. There are more than 100 judges in Shenzhen Intermediate People’s Court who have accepted legal training from HKU.

Chan said in an interview that it seemed as though his 30 years of work at the university had suddenly been denied, and even worse, he suddenly became the target of attack. Chan said he felt helpless.

‘Politically Unwelcome’

In a recently published article, Hong Kong Economic Journal special commentator Lin Yuet-tsang stated that the HKU pro-vice chancellor incident had evolved into a “Hong Kong version of the Cultural Revolution.” The mouthpiece media of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) labeled Chan as a “politically unwelcome person,” Lin added.

Lin wrote in the article that the CCP’s Cultural Revolution started in mainland Chinese cultural and educational circles. For example, Hong Kong’s Wen Wei Po newspaper launched an attack against Chan last November in the same style as Yao Wenyuan, who at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution published an article in Shanghai Wenhui Daily criticizing Ming historian Wu Han, Lin stated.

According to Lin, the means the CCP used to take over the power of the tertiary education sector can be seen in the Hong Kong University incident.

Lin gave the example that in May 1966, extreme leftists of the CCP put up the first poster of the Cultural Revolution in Peking University, criticizing the Party committee of Peking University. People’s Daily followed up quickly and published an editorial calling the public to overthrow “bourgeois experts, scholars, and authority.”

In March this year, Leung Chun-ying appointed Arthur Li as a member of the HKU Board of Committee. Li led the way in delaying the appointment of Chan, and then he successfully rejected the appointment on Sept. 29, Lin reported.

“Seizure of power in HKU has become a trend,” Lin stated. “The next step is to target the vice-chancellor. Other institutions will soon find themselves following the steps of HKU.”

Lin believes the nature of the Communist Party has never changed. Economically it becomes powerful, but politically it is leftist. According to Lin, Hong Kong is increasingly losing its high degree of autonomy, eventually leading to the staging of the Hong Kong version of the Cultural Revolution.

Translated by Susan Wang. Written in English by Sally Appert.