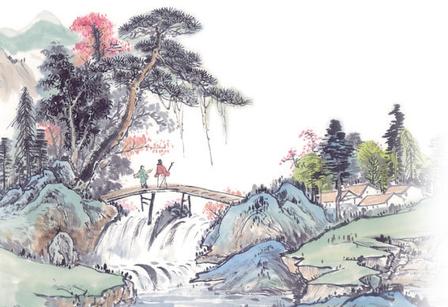

Rain drizzles ceaselessly at the time of Qingming Festival,

The traveller on the road is nearly spirit-broken.

Courteously inquiring where a tavern could be found,

A shepherd boy points to Apricot Flower Village in the far distance ahead.

When talking about the Qingming Festival, literally “Pure Brightness Festival,” many Chinese people will promptly recall this famous verse by Tang poet Du Mu (803–852), titled “Qingming,” a poem that they can likely still recite having learned it as young pupils.

Occurring on the 15th day after the spring equinox, and falling on April 5 this year, the festival takes place around the time of year when rainfall is common as the weather transitions to a warmer springtime.

Also called “Tomb Sweeping Day,” the Qingming Festival is an occasion when Chinese families remember and honour those before them by visiting their ancestors’ gravesites to clean the grounds and pay homage with flowers, prayer, incense, and other respectful offerings.

In this context, Du Mu’s poem describes the despondent state of a lonely traveller still on the road while others are already reunited with their families. The man is made all the more sad and gloomy by the nonstop rain.

The poem takes a bright turn to convey a sense of hope when the shepherd boy points the traveller in the right direction toward an inn. It will be a place where he can find shelter and lodging as well as drown his sorrows in wine.