WASHINGTON—Vladimir Putin easily won a third presidential term on Sunday, garnering almost 65 percent of the vote (with 90 percent of ballots counted at press time)—well above the 50 percent he needed to avoid a runoff round.

His nearest rival, communist Gennady Zyuganov was at about 17 percent.

There was never any doubt that Putin, who has been premier during his four-year hiatus from the presidency, would top 50 percent on the first ballot. Having to face an opponent in a runoff would be seen as weak, said Russia observers.

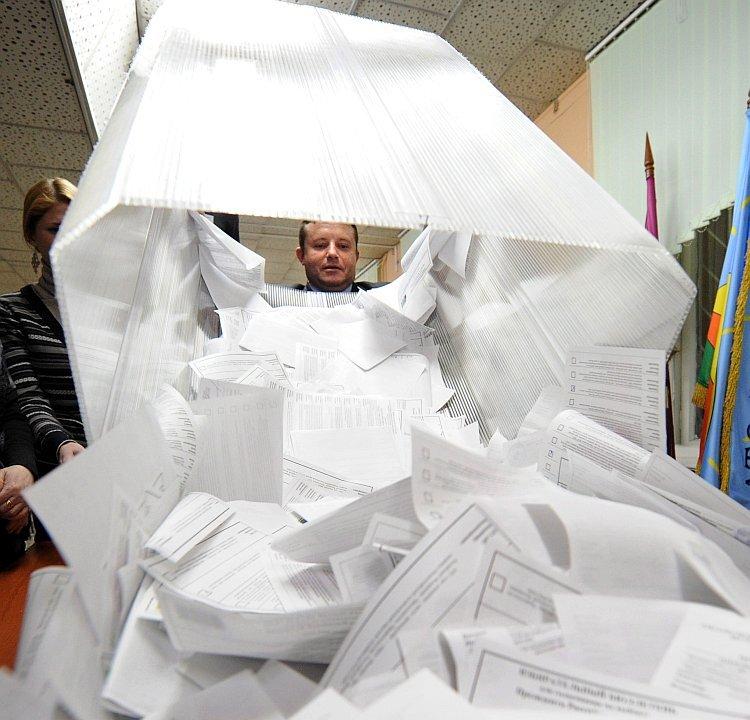

The opposition charges that voting violations were widespread in favor of Putin’s United Russia party, just as they were in last December’s parliamentary polls. That election triggered unprecedented protests in the country, bringing tens if not hundreds of thousands of people into the streets in the big cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Alexei Navalny, Russian dissident blogger, vowed that protests will continue after the election. On PBS “NewsHour,” Feb. 29, he said, “I do not know what the scale of the protest will be, but the fact that it will continue is quite obvious. It doesn’t matter how they count the votes, because all candidates should have been able to participate in the elections.”

Navalny is known for targeting corruption on his blog; he has emerged as a popular spokesperson among the social networks that is fueling the opposition movement.

Putin’s ‘Unfair’ Advantages

“All resources are being brought to assure Putin victory on the first ballot,” said Dmitri Trenin, a Russian citizen and director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, in the last days of the campaign. He was a guest speaker at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The Kremlin dominates television coverage—the predominant medium in Russia—and so Putin had far more exposure than the other presidential candidates.

“State television broadcast what they called ‘documentaries,’ which looked more like hourlong commercials glorifying Putin’s achievements,” writes Nikolay Petrov, a scholar at the Carnegie Moscow Center.

Petrov, a severe critic of Putin, said that Putin needed “to demonstrate to the political elite and the people that he is still the uncontested national leader and can win in the first round.”

Putin’s election rivals who were allowed to run were very weak competition—billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov, Communist Gennady Zyuganov, ultranationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky and former Upper House speaker Just Russia leader Sergei Mironov. Except for Prokhorov, all had run for president before and have shown themselves incapable of mustering significant support.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, former member of the Duma speaking on PBS “Newshour,” called the challengers “phony competition” that Putin selected himself. No one from the real opposition was permitted to register, he said.