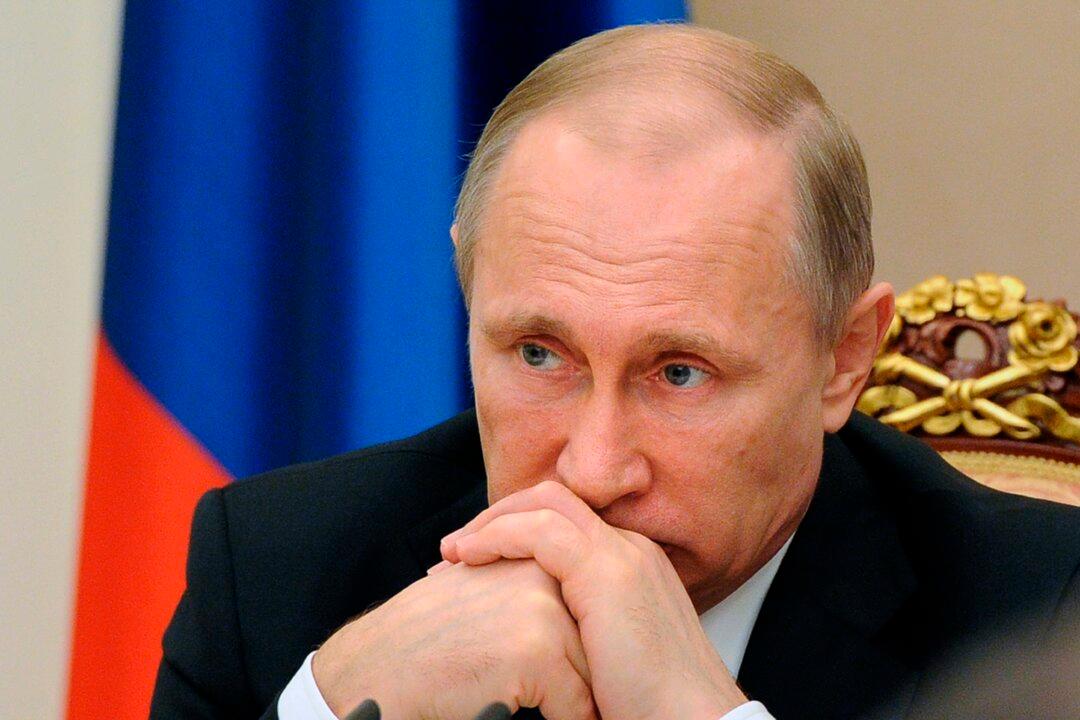

MOSCOW—With dozens of Russian combat jets and helicopter gunships lined up at an air base in Syria, Russian President Vladimir Putin is ready for a big-time show at the United Nations General Assembly.

Observers expect the Russian leader to call for stronger U.N.-sanctioned global action against the Islamic State group and possibly announce some military moves in his speech on Monday.

Putin appears to see the rise of the IS as both a major potential threat to Russia and a common cause that could help restore ties with the West, ravaged by the Ukrainian crisis. By claiming a new role in Syria, he may hope to lift Russia from the Ukrainian morass and rebuild its image as a top-tier global player capable of tackling IS, which he has called an “absolute evil.”

Fyodor Lukyanov, the editor of Russia in Global Affairs magazine, believes that Putin’s moves in Syria are intended to “take the dialogue with the West out of the Ukrainian impasse.”

“Syria and the Middle East in general are the problems that attract global attention, and we raise our status by returning there as active players,” said Lukyanov, who has strong official connections as the head of the Council for Foreign and Defense Policies, an association of Russia’s top foreign policy experts.

The Russian moves in Syria are also aimed at securing what is left of the Syrian state after a series of defeats suffered by President Bashar Assad’s army, and saving Alawites from being massacred, Lukyanov said.

Putin has been coy about his goals.

While the Russian deployment to Syria couldn’t be concealed, with giant military cargo planes and navy transport vessels shuttling back and forth for weeks to ferry troops, weapons and supplies, Moscow’s plans remain unclear.

Putin and his officials have said only that Russia has provided weapons and training to the Syrian military to help it combat IS. Asked if the Kremlin could send troops to fight IS, Putin answered that “we are looking at various options.” His spokesman said Moscow would consider Syria’s request for Russian troops to help combat the IS if Damascus were to ask.

Some key questions remain:

— Will Russia limit itself to providing weapons, training and advice to the Syrians as it has done before, or will it send its soldiers into actual combat?

— If they do enter combat, will the Russians fight exclusively against IS, as the Kremlin has pledged, or will they also target other groups fighting against Assad?

— Will the Russian forces conduct only reconnaissance missions and air strikes, or will they also engage in ground action?

By preceding his U.N. speech with the military buildup, Putin apparently aims to coerce the U.S. into talks.

“The Russian diplomatic strategy is to be taken into account by the United States, basically,” Dmitri Trenin, head of the Carnegie Endowment’s Moscow office, said in a conference call with reporters. “Russia is creating facts on the ground. Russia is not asking for permission to be in Syria, or to be doing things it’s doing in Syria, and that creates a position from which the Russians think they can get ... some kind of an understanding with the United States.”

Worried by the threat of Russian and U.S. jets clashing inadvertently in Syrian skies, Washington has agreed to talk to Moscow on how to “deconflict” their military actions. Last week, U.S. Defense Secretary Ash Carter had a 50-minute phone conversation with his Russian counterpart, the first such military-to-military discussion between the two countries in more than a year.

Israel acted similarly, with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visiting Moscow this week to agree with Putin on a coordination mechanism to avoid any possible confrontation between Israeli and Russian forces in Syria.

“Russia wants to switch the attention away from Donbass (eastern Ukraine) to Syria, where, as Putin has been saying all the time, core Russian and U.S. interests, and European interests, are very similar,” Trenin said.

But while the U.S. has agreed to hold military discussions with Russia, any quick cash-out for Moscow appears unlikely.

Washington and its allies view the Russian buildup with concern, worried that Putin would try to shore up Assad, whom Russia has shielded from U.N. sanctions and provided with weapons throughout the 4½-year civil war that has killed 250,000. The U.S. and its allies see Assad as the cause of the Syria crisis, and the continuing Russian support for him will not help warm ties.

And even if Moscow and Washington find common ground on Syria, Kremlin hopes that the U.S. and its allies will eventually lose interest in Ukraine and become more accommodating to Moscow’s interests seem illusory. Russia and the West have remained deeply divided by the Ukrainian crisis, and prospects for lifting Western economic sanctions against Moscow look dim as February’s peace deal has floundered.

Moscow’s military involvement in Syria could also create a host of new problems that Putin may find hard to contain.

Most analysts predict that if Putin openly commits his troops to combat in Syria, Russia will limit itself to air strikes and stay away from ground action. “There is no talk about a full-scale military operation and the deployment of a large contingent of troops,” Lukyanov said.

But even a limited Russian military action would anger Saudi Arabia, Qatar and other Gulf states, which would see it as an effort to prop up Assad, whom they have vowed to unseat. Diplomatic damage aside, Russia would also face potential military losses, and terror threats will rise.

“It will strengthen the perception of Russia as a target for radicals, and retaliation may come anywhere,” Lukyanov said.

IS already has threatened to strike back at Russia, which has fought two wars with separatists in Chechnya and has seen numerous deadly terror attacks in the past by Islamic militants.

On the battlefield in Syria, IS lacks sophisticated air defenses, but its forces still managed to down a Jordanian combat jet earlier this year. The group later released a video showing a captured Jordanian pilot being set ablaze while trapped in a cage.

Possible Russian military casualties in Syria could push the Kremlin to respond in an even more forceful way, creating the risks of escalation. “There is a risk of being sucked deeper into it, even though no one wants that,” said Lukyanov.