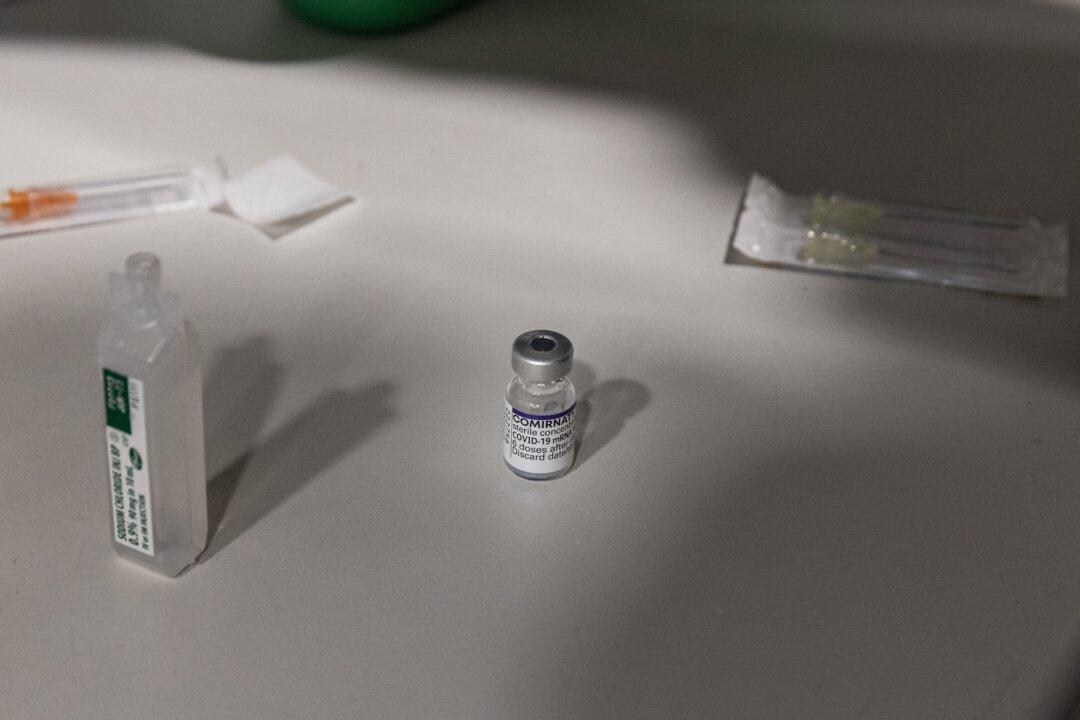

The new COVID-19 vaccines provide a boost to protection against hospitalization, although that shielding wanes within months, according to unpublished data presented on Feb. 24.

A bivalent Pfizer or Moderna booster increased protection against hospitalization initially by 52 percent, but that protection dropped to 36 percent beyond 59 days, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) researchers said.