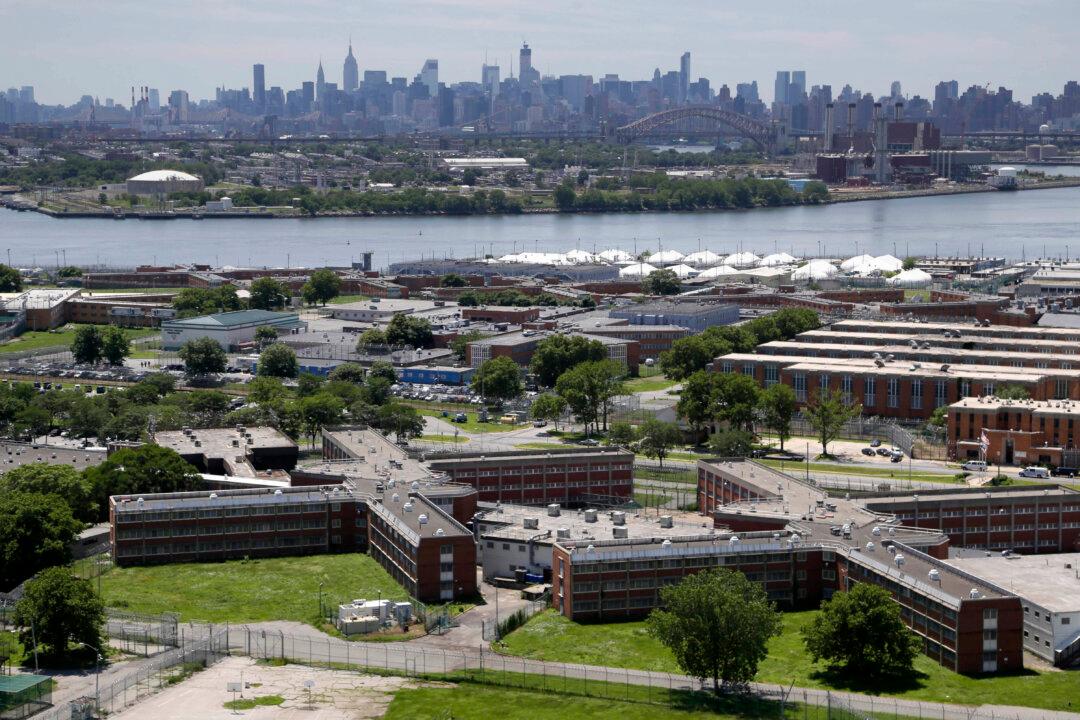

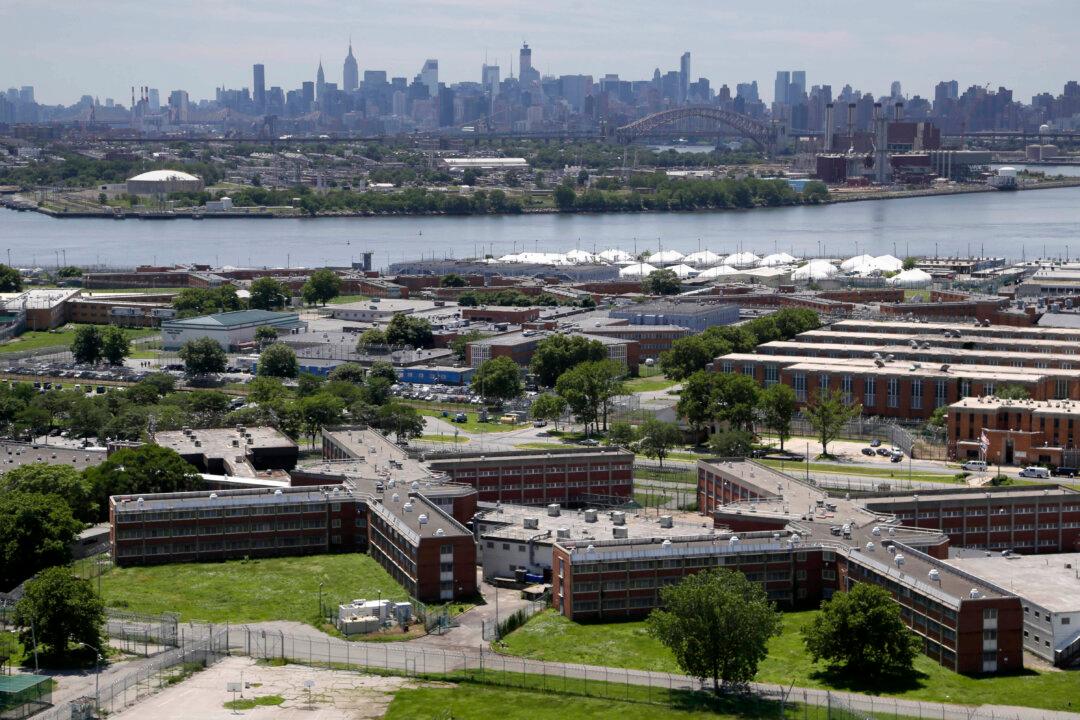

NEW YORK—Victor Woods shook uncontrollably, his body wracked by convulsions, as fellow inmates held him in their arms and shouted for help.

Amid the chaos inside a Rikers Island dormitory, surveillance video showed a lone figure of relative calm: a guard watching it all unfold as he sipped a cup of coffee.

“I’m not touching him,” the guard was quoted by inmates as saying.

Within hours, Woods, a 53-year-old unemployed tunnel worker who had been arrested a week before on heroin possession charges, was dead.

Woods was the seventh inmate to die in 2014 at Rikers.