Two police chiefs, two journalists, an elected official, two activists, a mental health advocate, a lawyer, and a professor walk into a bar. They talk in a thoughtful, civil way about police shootings, protests, and what the media gets wrong about that story. It was the Society of Professional Journalists—Georgia’s Police, the Media and the Public at Manuel’s Tavern in Atlanta on Oct. 31, 2015. I’m an officer on its board of directors. The police shootings program was my professional education passion project.

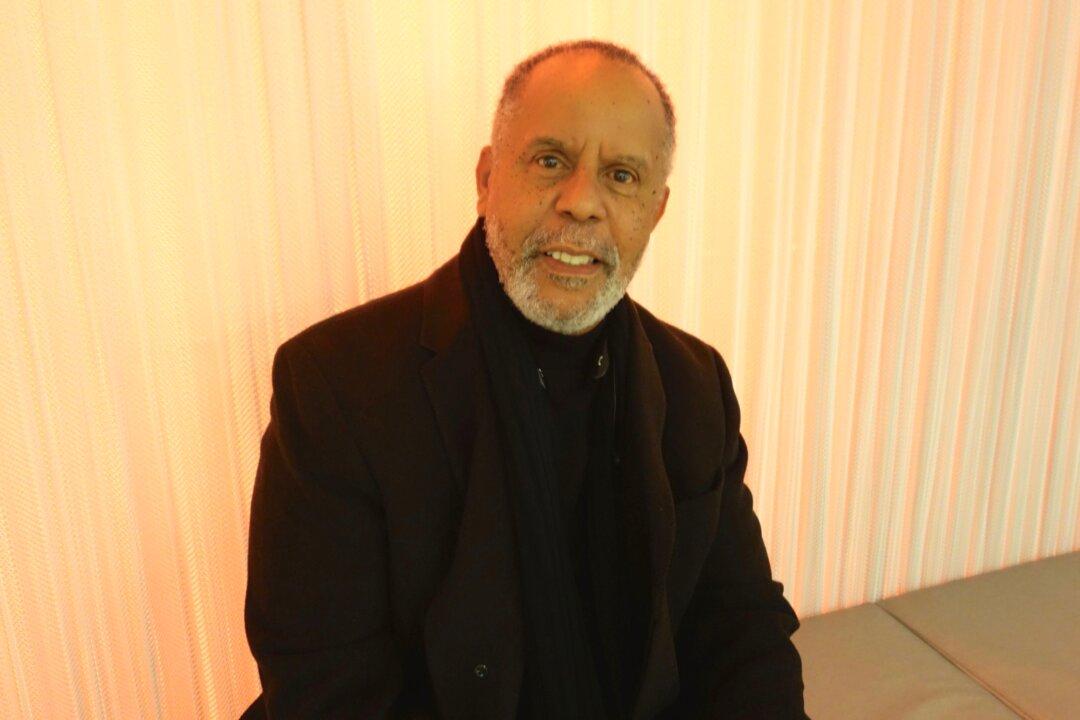

The Georgia chapter pulled together an all-star mix of voices. Peabody and Emmy award-winner Julius “Jay” Suber was one. Journalist George Chidi of Pine Lake City Council and the nonprofit Central Atlanta Progress was another. Dunwoody Police Chief Billy Grogan, Dr. Makungu M. Akinyela of Georgia State University, and Brookhaven Police Chief Gary Yandura sat in a row. Mental health advocate Lori Brickman, and lawyer Hollie Manheimer, executive director of the Georgia First Amendment Foundation contributed their expertise. All explored police shootings and what the media should do better. Sadly, Cobb County NAACP President Deane Bonner had to attend a funeral. She was missed.

Akinyela cited the 2012 Malcolm X Grassroots Movement report. It said a vigilante, an officer, or a security guard kills a person of color every 28 hours. According to Akinyela, it is common that “an officer has killed with impunity and nothing has happened.” Grogan listened respectfully and said, “I would have to disagree with that.” He said most of the millions of encounters between police and citizens are not violent. “Are there cases where police officers use force and they should not have? Yes, of course”—but police chiefs and the judicial system address the problem, in his opinion.