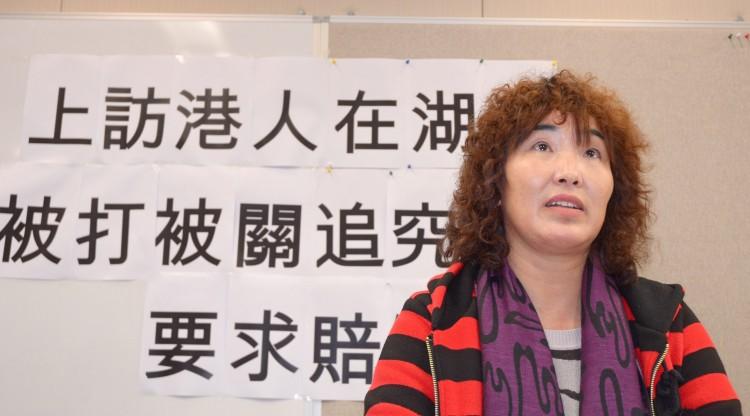

Earlier this month after learning that China’s Jingzhou City administration had tried to demolish her family home, Yang Xuecui hit rock bottom. She was already dealing with the fallout from a malpractice claim against a hospital that led to the assault of her now-hospitalized mother, and she was out of options.

“I felt so wronged,” Yang told Voice of America. “My house was on the verge of being demolished, my son was injured, my mother had been beaten and she is still in the hospital. I felt so helpless. When I tried to petition, there was no one I could turn to.”

According to the China Tianwang Human Rights Service (64Tianwang), out of desperation Yang positioned herself in front of Zhongnanhai, central headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and started to cut her wrist with a blade in an attempt to commit suicide. Police on patrol stopped her.

According to a letter posted by Yang on the 64Tianwang blog, she began petitioning after a medical malpractice incident involving her 13-year-old son in February 2010. Yang says the hospital falsified the case to avoid responsibility. In January 2011, after she attempted to petition at various state agencies, she said a doctor hired gangsters to beat up her mother, who was over 70 years old at the time. Yang has video evidence of the beating. Her mother suffered fractured bones and remains in the hospital.

Yang’s story of failed attempts to petition regime officials is not uncommon in China. On Aug. 17, Hong Kong petitioners Wang Yan and two others were refused entry to the Beijing West Railway station, where they were told that they were on a list of “unwelcome people.” They were forcefully returned to Hong Kong.

The number of petitioners disappearing from Beijing has increased as the 18th National Congress of the CCP approaches, according to 64Tianwang. Some self-proclaimed “human rights activists,” “journalists,” “National Congress representatives,” and “professors” ask petitioners for their petition materials and write down their personal information, including addresses and contact information.

Eager to get help, petitioners normally grant such requests for information without hesitation, and go missing a few days after such encounters. The average annual wage for petition interceptors has increased from 50,000 yuan (US$7,864) to 60,000–70,000 yuan (US$9,430–$11,000).

Despite the efforts of petition interceptions from the Chinese regime, the organizations handling letters and calls in Beijing are still facing crowds of disenfranchised citizens.

The person in charge of 64Tianwang, Huang Qi, told Voice of America, “The number of petitioners in Beijing can be said to have increased several times since the 17th National Congress. It is an estimation made by some veteran petitioners based on their experiences and observations, and the number includes petitions to offices including the National People’s Congress, the State Council Letters and Visits Office, and the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection.”

Huang Qi added that the Chinese authorities’ traditional practices against petitioners are still centered around retaining them in their local areas. Local authorities tend to take tough measures to suppress local petitioners in order to prevent them from going to higher authorities. The latest incident happened in Chengdu, Sichuan Province on Aug. 18 when the Dujiangyan Village representative Chen Shiying was beaten about the head and left bleeding by security forces.

Read original Chinese article.

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.