MIDDLETOWN, N.Y.—The clock rewinds to a plate of unfinished turnip cakes whenever Ellie Rao thinks of her dad, a bespectacled man with an oblong-shaped face whom Chinese police took from her when she was 4 years old.

They were seated together, relishing the beloved southern Chinese staple that Rao’s grandma had lovingly fried golden crisp, when a hard knock at the door made them drop their chopsticks.

Two men demanded to come in. They said they were from the water utility company and were “checking the meter.”

The phrase was a code word for police, as the men indeed were. Four or five more soon swarmed in. They dragged Rao’s dad away. From the apartment window, the girl could do nothing but watch her father’s lanky frame vanish into a white car, and then, from her life.

He never made it back.

He died less than seven weeks after police dragged him away.

For the young Rao, fear was part and parcel of living in communist China. And she was not alone.

Today, at Shen Yun Performing Arts, an upstate New York company that showcases “China before communism,” it is hard to meet someone who has not lived through such pain or knows someone who has.

This shared experience of suffering is, after all, what brought Shen Yun artists together. In each new production that takes place on the world’s stages every year, one theme is always present: the modern-day persecution of Falun Gong, a spiritual practice that Rao and other Shen Yun performers embrace.

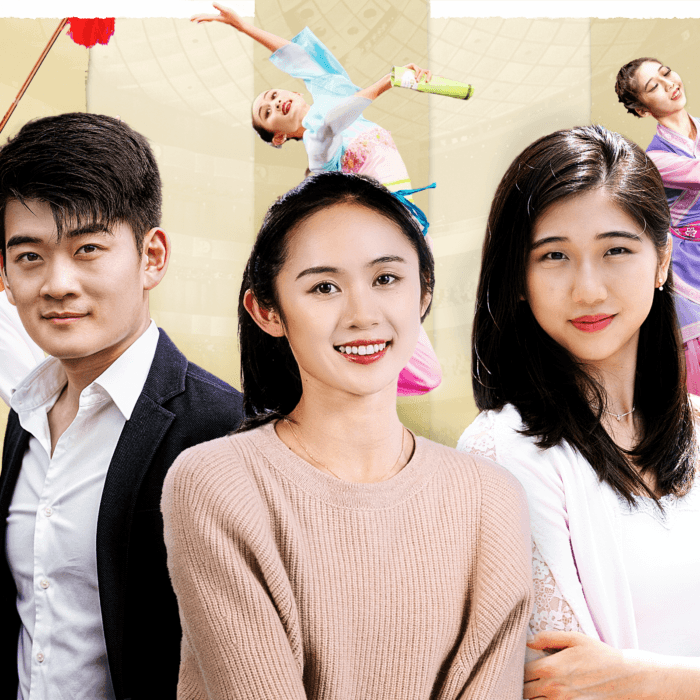

Rao is one of four Shen Yun principal dancers who recently opened up about the heartbreak they bore as children under that far-reaching suppression. They bore witness to the state terror that engulfed them and etched scars that took years to heal.

Now, having found a platform in New York state, they see it as their mission to keep the same scenes from repeating.

Traumatic Memories

One day, after the persecution campaign had come into full force, 8-year-old Zhao Jiheng came home from school and found the rooms emptier than usual.“Where’s mom?” he asked his father, who looked grave but made no answer. In a few days, Zhao’s father also disappeared.

After a year in jail, his mother came back a shell of herself, mute, hollow-faced, and worn. She no longer buzzed around in the kitchen to make tasty food for Zhao. Instead, she sat for long periods on the bed, unresponsive to questions from the unnerved child. Images from that time show that her teeth had blackened; several front teeth had cracked in half.

The carefree days Zhao had known were over.

Plainclothes police hovered around his mother’s beauty parlor on a near-daily basis. They took her away during politically sensitive anniversaries and often broke into her home with little explanation. Zhao’s father was away for years, on the run from police for refusing to renounce his belief in Falun Gong. Zhao’s classmates hit and shoved him, and teachers jeered at him publicly, enforcing the already pervasive state propaganda. Then, more than once, Zhao returned home from school to find his mother and their valuables gone, both taken by the police.

The repression was sending chills far beyond China’s border.

For years, visions of Chinese police haunted Sydney-born Chen Fadu in nightmares until she woke up sobbing. In some of those dreams, she had crammed herself in a corner, arms curling on her knees, as the police, batons in hand, towered over her. Other times, she ran breathlessly to shake them off, only to see her pursuers gain on her with each passing moment.

In real life, that was how they had treated her father, who died in 2001 shortly after Chen’s first birthday. Early that year, Chinese police arrested and tortured the man using electric batons after he traveled to Beijing to defend his faith. After returning home to southern China, police again showed up, dragging his badly bruised body from his bed in front of the wailing infant girl.

For Japanese boy Kenji Kobayashi, the weight of the persecution sank in on his seventh birthday.

That day, hundreds of miles across the ocean, a white police van sent his grandmother, a Falun Gong practitioner in the northeastern Chinese city of Shenyang, to a local psychiatric facility to force her to renounce her faith. Using psychiatric facilities as torture bases has been common practice in China since the persecution began.

When the news reached Tokyo, Kobayashi and his younger brother hugged each other and cried.

The guards put the woman, then almost 60, in a cell with 24-hour lighting to keep her from sleeping. They followed her everywhere, including to the bathroom. During the day, they made her sit on a low stool and watch propaganda videos. Even expressions mattered. One absent look, and she was reprimanded.

That month of ordeal sapped her health. When she escaped to Japan that October, Kobayashi met her at the airport and was alarmed to observe her swath of white hair and stooped back.

“At least she made it out alive,” he told The Epoch Times. “Considering everything, we are still the lucky ones.”

‘Keep Up What You Believe’

Once his grandmother was in Japan, Kobayashi had to help keep her there.Every day after school, the second grader dropped his backpack, grabbed a clipboard, and biked to the train station 15 minutes away.

He and his grandmother propped up a board showing her image.

“Please help me,” he pleaded to every passerby. To anyone who showed attention, he showed them his clipboard—attached was a petition seeking to allow his grandmother to stay in Japan. Whenever there was more time, he and his grandmother took a train around the 23 city districts, soliciting support from legislators.

Signature, signature, signature. Kobayashi thought of nothing else. In a month, he persuaded more than 2,400 people to sign. His grandmother was granted asylum a few months later.

The mother and daughter traveled to 45 countries in five years, a journey that earned them the Turtle Award from the Australian Altruism Foundation in 2006. They were the first ethnic Chinese honorees.

Zhao recalled that when he was in middle school in China, a group of police officers pressured him to persuade his mother, then in jail, to give up Falun Gong.

“If you want your mom to get out early, cry and beg her,” Zhao remembered them saying just before a prison visit.

Zhao kept his mouth shut. But when he came face to face with his mother, he did not hesitate, saying: “Mom, keep up what you believe. I support you.”

The police cut off the visit shortly afterward.

Zhao said he has no regrets and would do the same thing again.

“If you know something’s good and you say it’s bad, that goes against my conscience,” he told The Epoch Times.

The young Kobayashi, after the petition campaign, continued to think of ways to counter the persecution in China. A baseball fan, he watched the champions giving ebullient interviews and dreamed of becoming one of them. If he had a following, if he got on TV, he could tell the world about what had happened to his grandmother and other families, and people would listen.

Instead, a night watching Shen Yun at the theater opened his eyes to a different platform. At age 12, he flew to upstate New York to study at Fei Tian Academy of the Arts, the training ground for many Shen Yun artists.

By then, Rao and Zhao had escaped to the United States as refugees. In a few years, all four were on the same campus, leaning into a millennia-old art form to interpret their past and connect to their cultural roots.

For the painfully shy Rao, dancing was liberating. It freed up her body to express itself and to be understood—a testament, in essence, that “actions speak louder than words.”

Shen Yun has brought stories similar to her own to the stage, something as precious to her as it is emotional. She said she remembers playing a fairy one time who consoles a young girl coping with the loss of loved ones killed for their faith.

She held the hand of the girl, played by her friend, and felt a tear drop into hers. At that moment, she said, she felt as if they had become one.

‘Greatest Dream’

It has not always been smooth sailing. Shen Yun, despite being based in the United States, has faced incessant harassment from Chinese operatives.The whistleblowers specifically identified one individual as being used by the CCP to spread “malicious” information against Falun Gong.

The man, who also runs a YouTube channel, has called Shen Yun managers his “enemies” whom he is trying to have sent to prison. He has bragged about filing complaints against Shen Yun with New York state authorities in the hope of triggering legal action. He has also encouraged others to do the same.

He also appears to have played a key role in a recent series of articles published by The New York Times attacking Shen Yun.

“I was the one who introduced people [ex-Shen Yun performers] to the New York Times, especially for the initial interviews,“ he wrote on social media platform X. ”They found additional people through that.”

The FBI marked the man as “potentially armed and dangerous” after he was spotted near the Shen Yun campus in upstate New York in 2024. He was subsequently arrested and is facing charges of possession of illegal firearms.

The performers sometimes share a sense that they are on a battleground, reclaiming their past inch by inch from the CCP’s grip.

In one dance piece, Zhao portrayed a Chinese police officer in a grisly scene that depicted the regime’s practice of harvesting organs from Falun Gong practitioners.

Right in the middle of it, an incredulous audience member exclaimed that it could not be real.

Zhao felt stung. But he could also empathize. How could someone living in the free world find it easy to believe that such bloody acts exist in the 21st century?

“However hard he thinks, he just can’t fathom the CCP being that evil,” Zhao said.

Today, the landscape is different, at least in the United States.

There is no baseball stardom, but touring with Shen Yun has taken Kobayashi to top-notch theaters around the globe to perform in front of thousands of people.

On stage, he has heard laughter, applause, and whistles and seen tears and smiles. During the curtain call, the standing ovation keeps him going.

“It’s like, they really do get it,” Kobayashi said. When that happens, he said, whether they know about him or not is not important. He just feels honored to be there—a part of the mission.

Kobayashi has not set foot in China. Rao, Chen, and Zhao have also not returned since leaving the country behind.

Rao said she hopes that one day they can go back, just to perform. One day in the near future.

That would be a future in which no one anywhere has to fear losing his or her dad for practicing truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance.

“It’s my greatest dream,” she said.