WASHINGTON—Trafficking women and girls is human exploitation that would seem to have no place in a civilized world. Can you envision a world without the coercion, kidnappings, abuses, and profiteering of human trafficking?

How can future perpetrators of these crimes be changed so they don’t do it?

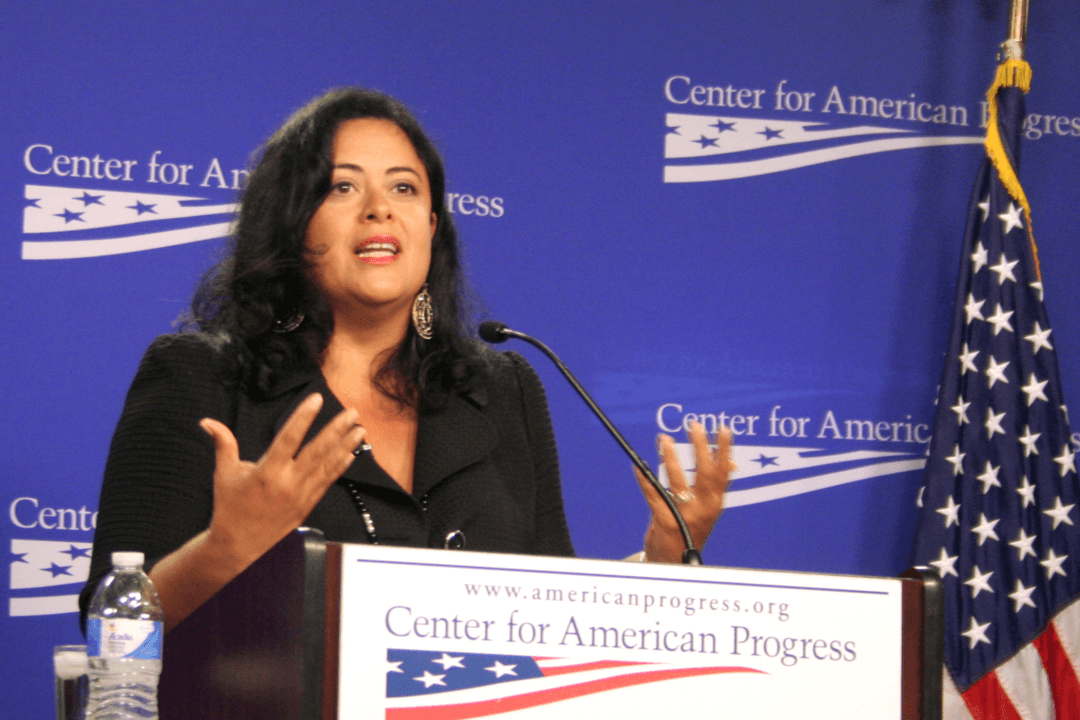

Maya Soetoro-Ng, peace advocate and assistant professor of the University of Hawaii’s College of Education, provided some answers Aug. 14 at the Center for American Progress (CAP).

Soetoro-Ng, 43, is the maternal half-sister of the 44th president, Barack Obama. Their mother was anthropologist Stanley Ann Dunham, who died in 1995.

Soetoro-Ng has developed strategies and mental exercises to help others understand the mindset behind trafficking. Her aim is to rehabilitate victims and put into place outcomes to prevent trafficking in the long term. Her methods are applicable to all anti-social behavior, not only trafficking.

The trafficking issue was briefly introduced before Soetoro-Ng spoke. The CAP announcement for the event was read aloud: “An estimated 3 million children are currently exploited in India’s sex trade. The vast majority of trafficked women and girls usually come from the poorest, most disadvantaged backgrounds in India. … Every day in India, 200 women and girls enter prostitution, and 80 percent of them do so against their will as victims of trafficking.”

Soetoro-Ng, who refers to herself as a “peace educator,” said she would refrain from talking policy and offered that her brother’s administration addresses policy. She wanted to speak from a different perspective. With profits from trafficking in the billions, and millions of people impacted, we shouldn’t look to just governments for solutions, she said.

“Even without a background in policy or law enforcement, perhaps you can build greater awareness or strengthen pro bono networks, build resource centers, [and] training centers; you can do outreach and you can educate, and very important to me—powerful acts of storytelling,” she said.

Storytelling

Storytelling is integral to her teaching. She is the author of a children’s book “Ladder to the Moon.” The book opens with a view of the moon from the Earth’s perspective and ends with a picture of Earth from the moon’s perspective. She said that when she was growing up in Indonesia, her mother, whom she humorously referred as a kind of lunatic, sometimes woke her in the middle of the night to view the moon. Being awakened was irritating but she always enjoyed these moments with her mother.

Her mother told her that wherever one is on Earth, the moon and its phases look the same. Inspired by her mother, the book was published in April 2011.

Of course, her elder brother, the president, was an accomplished author before he entered politics. Soetoro-Ng told The New York Times, “I think our mother definitely influenced us both. She was interested in stories, in storytelling.”

The concept of “constantly shifting perspective” that a young child is introduced to in her book is key to her Weltanschauung. About trafficking, Soetoro-Ng says we have to be “nuanced in our thinking” and consider the larger set of circumstances. She emphasized that peace educators like her “need to meet the community where they are at some level.” In this process of examination, we shouldn’t be arrogant.

“If we are to be culturally responsive, we have to understand the reason why you have perpetrators,” she said.

In addition, moral courage and sacrifice are essential for change. She admires Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King because they could take something “soft” and make it “sharp and explosive” and brought about “enormous changes.” She said she did not expect people in the audience or herself to become martyrs but she asked that we “sacrifice” for the “long-term vision.”

Creating Gardens

As a teacher for peace, Soetoro-Ng works with creating “spaces” or metamorphic “gardens.” She says we can design gardens in homes and classrooms—a place to nurture reflective silence. The garden may involve some symbols or something symbolic such as a bench where people engage in conflict mediation.

Here is how she worked in her school with the Muslim-Christian conflict. She asked the Muslims to write down what would be the ideal garden. This entails the “shapes, sounds and images that warm them and bring about a sense of peace.” She asked the Christians to do the same. Then she asked each to create the others’ garden, “literally tending to each others garden.” Soetoro-Ng said this kind of work can be a “tremendous source of healing.”

Cuci Mata

Soetoro-Ng said that we can see ourselves, the world and our potential, and the beauty within ourselves and externally by “washing the eyes.” She drew upon the Indonesian phrase “cuci mata,” which means, to wash the eyes. It’s “changing not necessarily the way we look, but the way we see,” she explained.

The perpetrators and victims of trafficking can be healed and trafficking prevented through cuci mata, which can be applied to organizations as well as individuals. It’s giving the parties an opportunity to wash their eyes, she said.

She illustrated the method when teaching high school students about conflict resolution.

“I would always have the kids who were the bullies, the gang leaders, and the class clowns be the negotiators and the mediators.”

The reason was because it allowed them to see themselves differently. “They were already hungry for attention, already dynamic, and leaders. Giving them the tools to engage in benevolent leadership reminds them they can do that too.” Their self-identification is altered as they learn that others will listen “even when they are speaking softly.”