The basic murder victim of war is the truth. Thereafter, the morticians of public policy proceed to embalm human reasoning. It is a militant aggression against the spiritual existence of any creature’s right to hope that there can be life without assault. The weapon of choice by war practitioners is deceit, because history shows us once you get a people to believe an outrageous lie, you can get them to perform acts of outrageous moral and social criminal destruction.

Secretary of War (the title was more honest back then) Henry Stimson, said: “In the State Department there developed a tendency to think of the bomb as a diplomatic weapon. Some of the men in charge of foreign policy were eager to carry the bomb as their ace-in-the-hole… American statesmen were eager for their country to browbeat the Russians with the bomb held rather ostentatiously on our hip.”

Man, to be politically correct, has a particularly unique drive—absent in other animals, but an authentic hunger in man—this desire to industrialize all he can. Show a man a firecracker, and within a reasonable period of time he will show you an anti-tank explosive.

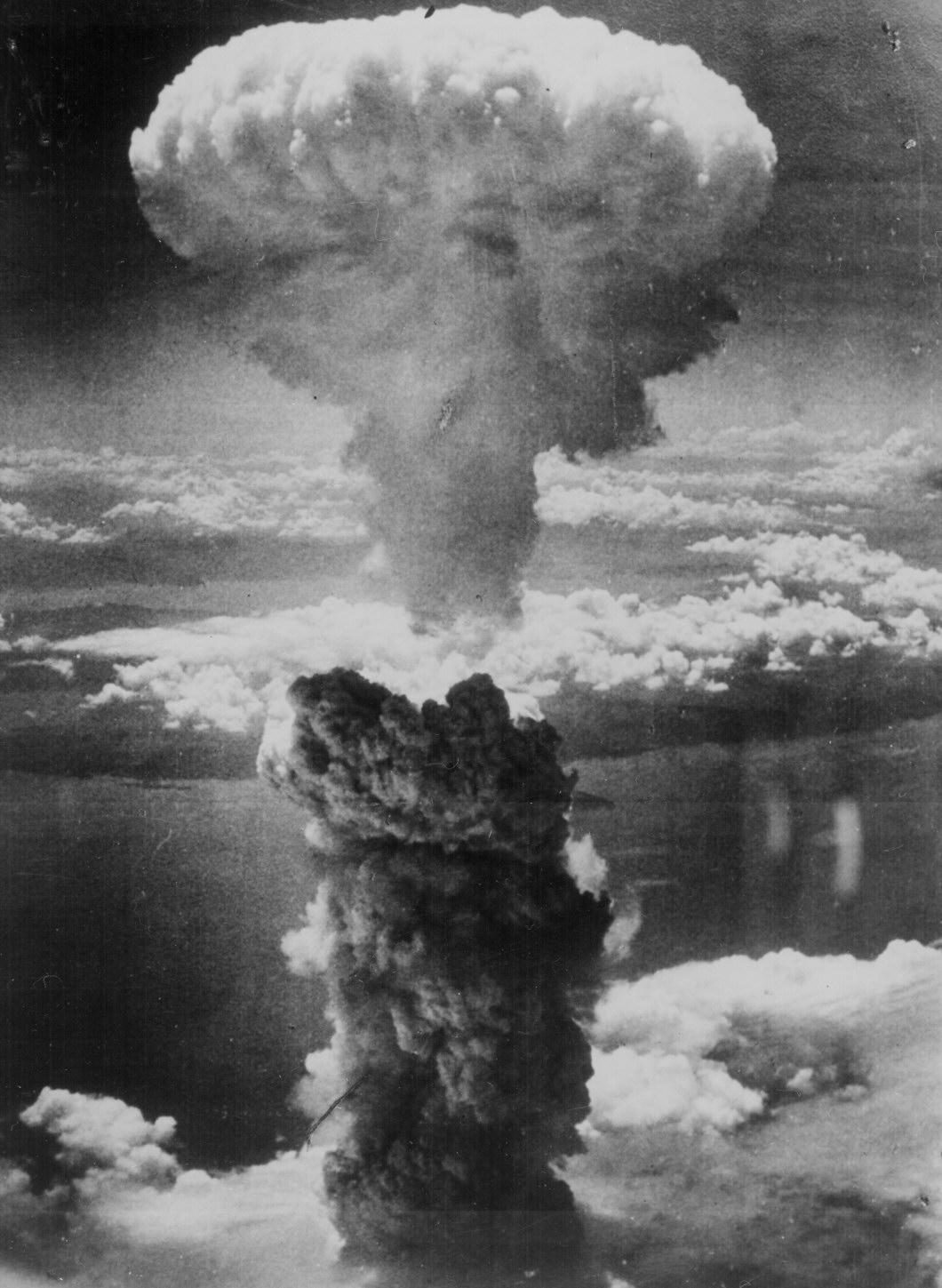

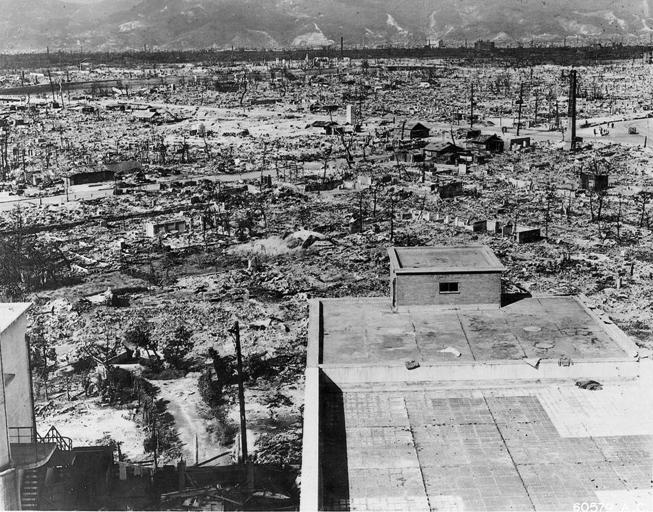

Nuclear energy is explosive—the biggest anti-everything explosive ever imagined. It was born in an endless chain of power egotism, and it was introduced during a war so there could be no argument about it being the right thing to do.

The crime itself may be conceptual; just to conceive of such a mass homicide device, let alone use it, and to execute the plan to use it for unheralded mass civilian bombing, is an assault on human evolution. What’s more, to industrialize this ticking, infectious, destructive device, which bleeds toxic radioactivity, as a means of industrial energy profiteering, when solar and wind power are there to develop, would appear to be spiritual suicide.

Paul Tibbets was the pilot of the plane that dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima, the plane was a Boeing B-29 Superfortress, a four-engine, propeller-driven, heavy bomber that was flown primarily by the United States during World War II.