No city in America can match New York’s broad array of taxes—more typical of a state than of a municipal government. Most New York City residents and businesses are subject to combined state and local tax rates far exceeding national norms. Such high taxes are a headwind against economic growth: they add to overhead, cut into profits, and make it costlier to employ people.

It was easy for politicians to ignore these effects from 2003 to 2008, when the economy was growing—even though the expansion, by boosting local tax revenues, provided a golden opportunity to reduce city tax rates and streamline a dauntingly complex tax structure. But instead of seizing the opportunity, Mayor Michael Bloomberg left the structure essentially untouched and the tax burden even heavier than he found it. Tax collections have doubled since Bloomberg took office in 2002, growing about twice as fast as New York’s economic output during the same period.

And now that the finance bubble has burst and income-tax rates have risen at both the federal and state levels, New York is at a more pronounced competitive disadvantage with cities that don’t squeeze their citizens as tightly. Wall Street, New York’s revenue gold mine since the mid-1980s, is retrenching, and in an era of slower growth, businesses will be less willing to shoulder costs that they can avoid by relocating. If the next mayor merely holds the line on city taxes, the result will be a real erosion of the local revenue base. To compete effectively for the jobs and investments of the future, the city needs to reduce taxes.

High Property Tax

The high cost of doing business in New York begins with its high property taxes. Under Bloomberg, they have been the fastest-growing component of city tax collections, up 110 percent since fiscal year 2002. To an extent, that growth reflects the delayed impact of increased property values during the final term of Bloomberg’s predecessor, Rudy Giuliani, because annual changes to assessed values are capped by law. But it also reflects the enduring impact of an 18.5 percent hike in the property-tax rate—the largest such increase in the city’s history, and passed at Bloomberg’s behest in late 2002.

New York’s property-tax system is widely acknowledged to be a complex and inequitable mess. Property in the city is divided into four classes: single-family residential; multifamily residential, which includes most apartment buildings; utility; and commercial. Each class is assessed and taxed at a different share of market value. The system, which dates back to a state-enacted “reform” in the early 1980s, is expressly designed to overtax commercial property and landlords while giving a break to homeowners.

Since Bloomberg’s hike, the disparities among the tax classes have only gotten worse. Average property taxes on single-family homes remain low by both regional and national standards. But the effective tax rate (that is, as a share of market value rather than assessed value) on a 20-unit apartment complex in New York is double the national urban average, according to a study issued by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and the Minnesota Taxpayers Association. The same study finds that New York’s effective tax rate on commercial buildings is at least 76 percent above the national urban average. Of the 50 largest cities covered in the study, only Philadelphia and Detroit impose higher commercial property taxes. In midtown Manhattan’s prime office space, the average commercial property tax in 2011 was more than triple the average for all major cities, according to the Studley Effective Rent Index.

City Income Tax

If property taxes were the only area where Gotham stood out, its other competitive advantages would still make it attractive to many employers. However, New York is also one of the few American cities with its own income tax. Indeed, it’s one of the few major cities to tax personal and business income—on top of similar taxes levied by the state, of course. The city imposes its personal income tax on residents at rates that rise as high as 3.9 percent on incomes over $500,000. And the state’s personal income tax tops out at 8.8 percent on incomes starting at $1 million, under a supposedly temporary surtax that Governor Andrew Cuomo and the state legislature recently extended through 2017.

Together, those two rates yield a combined marginal rate of 12.7 percent on top earners—the country’s second-highest, after California’s 13.3 percent rate, and by far the highest in the Northeast. As of 2009, the latest year for which data are available, the highest-earning 1 percent of New Yorkers—roughly 35,000 households with incomes starting at $493,439—generated 43 percent of Gotham’s personal income-tax revenues, according to the city’s Independent Budget Office.

New Yorkers who are self-employed or own shares in professional business partnerships can pay even more under the city’s unincorporated business tax (UBT), an additional levy that takes 4 percent of income above $100,000. For New York residents subject to it—including many lawyers, medical specialists, and partners in unincorporated hedge funds and private equity firms—the UBT can effectively raise the marginal state and local income-tax rate to 15.8 percent, easily the nation’s highest. The UBT also functions as a commuter tax, hitting the profit shares of nonresident co-owners of unincorporated New York City firms at a top rate of 12.8 percent.

As for companies, larger ones doing business in New York City get socked by a corporate income tax of 8.9 percent. Once those firms add New York State’s similar tax, they’re paying an incredible 17.5 percent of their New York-allocated net income—easily the highest rate in America and towering over the maximum rates in nearby states.

The city and state also impose special taxes on banks. And New York, alone among major cities, makes commercial tenants pay taxes on the rent that they pay. Those tenants are already paying property taxes through their rents (since landlords generally pass the cost of the taxes along to them), meaning that the arrangement amounts to a tax on a tax. Mayor Giuliani eliminated the tax in the outer boroughs, but it still applies to commercial rents in Manhattan south of 96th Street.

Cyclical Vulnerability

By remaining so dependent on income taxes, New York has made itself more vulnerable to cyclical economic swings. Between fiscal years 2003 and 2008, the city’s personal and business income taxes skyrocketed by $7.3 billion. But in the wake of the financial crisis and recession, revenues from those taxes dropped by $2.4 billion in 2009 alone and have yet to recover to pre-recession levels. Only the property tax held steady through the recession, supported by a steady stream of phased-in assessed value from previous years.

The city’s overall tax policy doesn’t spare the middle class. Once you add state levies, New York City’s tax burden on a family of three with an income of $50,000 is $909 higher than the average for the nation’s largest cities, according to a 2011 survey by the District of Columbia’s chief financial officer that included income, property, sales, and auto taxes in its calculations. But that tax gap grows with income: a three-person New York household earning $150,000 pays $5,980 more than the big-city average.

Not surprisingly, New York looks worst compared with low-tax cities, such as Houston, where the family with an income of $150,000 would pay $12,240 less. But Gotham also manages to out-tax cities with free-spending traditions. The combined tax bill for the $150,000-a-year family is $3,047 lower in Los Angeles than in New York, $3,997 lower in Chicago, and $5,410 lower in Boston.

Balancing and Cutting

Bloomberg kept the city’s annual budget in the black by squirreling away some surplus tax revenues in reserve funds. Those are now almost depleted, which will make it much harder to balance the budget, starting in fiscal year 2015.

But that doesn’t mean that the next mayor can’t start to ease the tax load. When Rudy Giuliani took office in 1994, he faced a more severe fiscal crisis than the one that Bloomberg’s successor is likely to inherit. Yet Giuliani’s first budget, even while it reduced spending, included a small cut in the city’s hotel tax. The cut amounted to just a single percentage point, but it sent an important message: that the city would try to nudge down its tax burden every year, even if only by a little.

Under Giuliani, the city lived up to the promise. City tax revenues as a share of gross city product fell steadily under his administration, dropping from 6.8 percent when he took office to 5.6 percent in fiscal year 2001 (before the recession and 9/11 attacks temporarily knocked them even lower). By the time Giuliani left office, city tax cuts totaled $2.4 billion.

Unfortunately, Bloomberg reversed the progress on tax cuts made under Giuliani. Under Bloomberg’s administration, city taxes as a share of gross city product have returned to the levels of the late 1980s and early ’90s. “We cannot raise taxes,” he proclaimed in his January 2002 inaugural address. “We will find another way.” But his resolve vanished within months.

The mayor felt that he had little choice: Giuliani’s last budget wasn’t balanced beyond fiscal year 2002, and the combined effects of 9/11 and the recession were dragging revenues well below Bloomberg’s initial budget forecast. So he turned to the property tax, the only major city levy that the city council can raise or lower without state legislation, and requested a 25 percent increase, which the council reduced to the 18.5 percent figure mentioned above.

Then, in 2003, Bloomberg persuaded Albany to approve a temporary, three-year boost in the city’s personal income tax and sales taxes. As it happened, that increase took effect at the same time as a much larger cut in federal taxes—and the economic boom that followed raised revenues so quickly that the temporary hikes were allowed to expire on schedule, at the end of 2005. A few years later, in fiscal year 2009, the city added slightly to its already high sales and hotel taxes to shore up revenues.

Bloomberg hasn’t sought a raise in residents’ income taxes since the temporary hikes of 2003, but he was stuck with one in 2010, when the state repealed the part of a program called School Tax Relief that subsidized lower city tax rates for high-income households. The state had already hammered the city’s competitiveness with its 2009 enactment of a temporary “millionaires’ tax”—initially, a rate hike of up to 31 percent on incomes starting as low as $300,000. At the end of 2011, Cuomo modified that increase to start at incomes of $1 million and extended it, as part of a package that included small rate cuts for the middle class. The governor and legislature have now extended the high rate again, combining it with a few more small reductions targeted to middle-class families.

Top Marginal Income Tax 52 Percent

Meanwhile, the recent budget deal in Washington has boosted marginal federal tax rates to their levels before the Bush tax cuts, with extra added to help pay for Obamacare. Thanks to the federal and state increases, the highest marginal income-tax rate in New York City is now 52 percent, the highest it’s been in nearly two decades.

And it may not stop there. President Barack Obama’s latest budget proposes a cap on itemized deductions for high-income filers, and Senate Democrats want to raise taxes in unspecified ways on households earning roughly $250,000 or more. Congressional Republicans oppose further tax hikes, but they would back a compromise that closed loopholes for the wealthy, the largest of which is the deduction for state and local taxes. If that deduction were eliminated, New Yorkers’ total taxes would rise even higher, while citizens of states like Florida and Texas, which have no income tax, would see no change.

Worse, two of the leading mayoral candidates—Bill de Blasio, the city’s public advocate, and John Liu, its comptroller—have called for increases in the city’s marginal income-tax rates. City council speaker Christine Quinn and former comptroller Bill Thompson say that they don’t favor an increase for now, at least, but both embraced income-tax hikes to close budget gaps as recently as a few years ago. Not to be outdone, former congressman Anthony Weiner, testing the waters for a mayoral run this spring, proposed a middle-class tax cut to be financed by “a reasonable new tax rate for the wealthiest 1 percent of New Yorkers.”

City Needs Lower Marginal Rates

What the city needs is just the opposite. High marginal rates, on both business and personal income, create a disincentive to earn and invest money in the city—and for the most highly mobile taxpayers, they are easy to avoid. There’s little dispute on this general point.

The liberal Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz was merely expressing economic orthodoxy when he wrote in a textbook that income taxes “have a particularly distortionary effect on location decisions of wealthy individuals; they may choose not to live and work in a location where their productivity is highest because the net return (taking into account the additional taxes they must pay on their capital income) is lower.” Stiglitz nevertheless endorsed an early version of New York’s “millionaires’ tax” in 2008.

New York’s taxes illustrate the principle. In a 2003 paper, economists Andrew Haughwout, Robert Inman, Steven Craig, and Thomas Luce found that local income and wage taxes in New York City and Philadelphia had “significant negative effects on city employment levels.” Their conclusion: “Cuts in these tax rates are likely to be an economically cost effective way to increase city jobs.” Other economists have come to similar conclusions about the negative impact of high marginal tax rates on private employment.

So it’s important to start moving city taxes in a more competitive direction: down. And any cuts should apply across the board, rather than being targeted to those who would yield the maximum political gain—the thrust of some current proposals, such as Liu’s, for middle-class tax breaks financed by tax hikes in higher brackets.

Phaseouts and Restructuring

Picking up where Giuliani left off at the end of 2002, the next mayor’s first budget should include a multiyear phaseout of an income-tax surcharge first imposed under Mayor David Dinkins. That would reduce the top income-tax rate from 3.9 percent to 3.4 percent, its lowest level since 1989.

The remaining commercial rent tax in Manhattan should be phased out as well. If the next administration merely began to eliminate the surcharge and the rent tax in its first budget, it would send economic decision-makers a signal that the city was going in the right direction, as Giuliani’s 1994 hotel tax cut did.

A more ambitious way to make New York attractive to business would be to restructure the property tax to stop favoring homeowners at companies’ expense. In the past, the city council and the state legislature have viewed that proposal as a political third rail. But at the very least, they should make sure that any future property-tax reduction applies to all property owners—unlike Bloomberg’s politically motivated $400 rebate for homeowners only, repealed in 2009.

In recent years, Bloomberg’s most visible contribution to debates on tax policy has been his (correct) argument that higher income taxes would drive away businesses. But his rhetoric, like his record, hasn’t been consistent on that point. In 2003, for example, he defended his tax increases by comparing New York to “a high-end product, maybe even a luxury product.” The city offered “tremendous value, but only for those companies able to capitalize on it,” he explained.

Well, if there’s any company “able to capitalize” on New York in exchange for paying its crushing taxes, it should be NBC—the TV network long headquartered at Rockefeller Center, where “Live from New York!” became a national catchphrase.

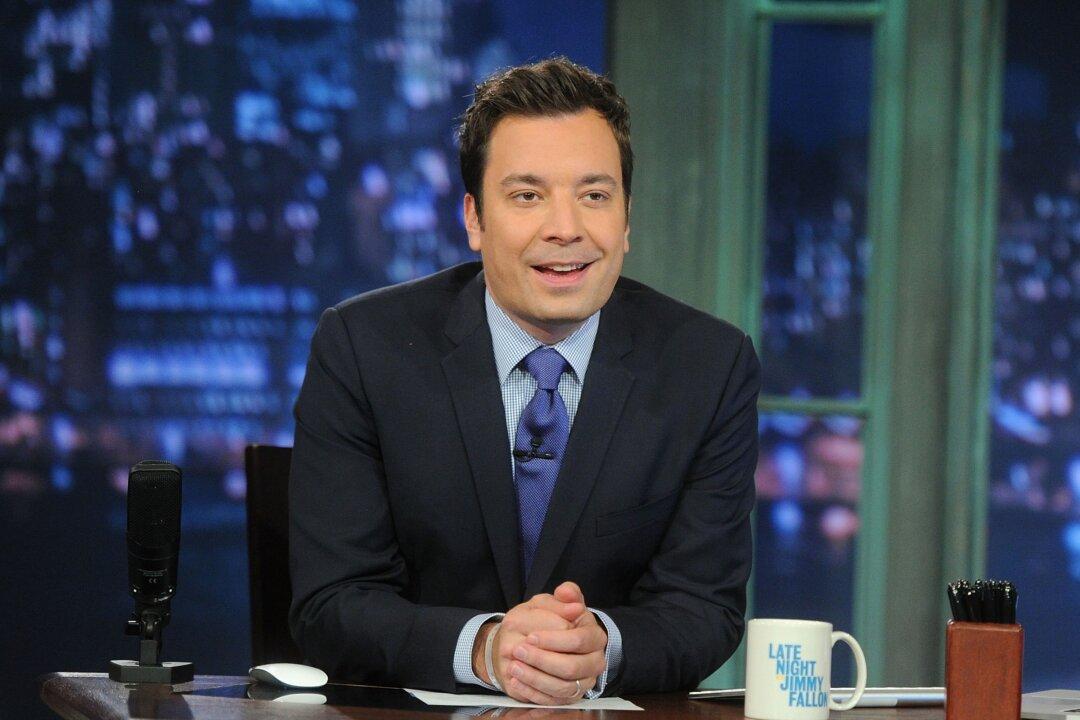

Yet NBC didn’t formally announce its recent decision to return The Tonight Show to its 30 Rock birthplace until the New York State Legislature approved a special tax credit designed to subsidize the construction of a new, multimillion-dollar studio for the show. Plus, the show’s new host, Jimmy Fallon, is a Manhattan resident who was born in Brooklyn, was raised in the Hudson Valley, attended college in Albany, and forged his career mainly in New York. If even NBC and Fallon won’t work in the Big Apple without getting a break from its oppressive taxes, who will?

E. J. McMahon is a senior fellow with the Manhattan Institute and its Albany-based Empire Center for New York State Policy. This article was adapted from City Journal’s special issue, “After Bloomberg: An Agenda for New York.”