You might not guess it from the Republican governor or GOP-dominated legislature, but Ohio is proving itself the most progressive state in the union when it comes to youth prison reform.

The Buckeye State has shifted away from punishing kids who get ensnared in the juvenile justice system to rehabilitating them, and it’s saved money doing so.

“What we’ve done in the past is treat the children who are incarcerated like mini adults,” explained Linda Janes, the deputy director of Ohio’s Department of Youth Services. “We know better now through research and through all kinds of evidence that that’s a mistake. Children have to be treated like children.”

That conclusion is good for youth offenders and good for society.

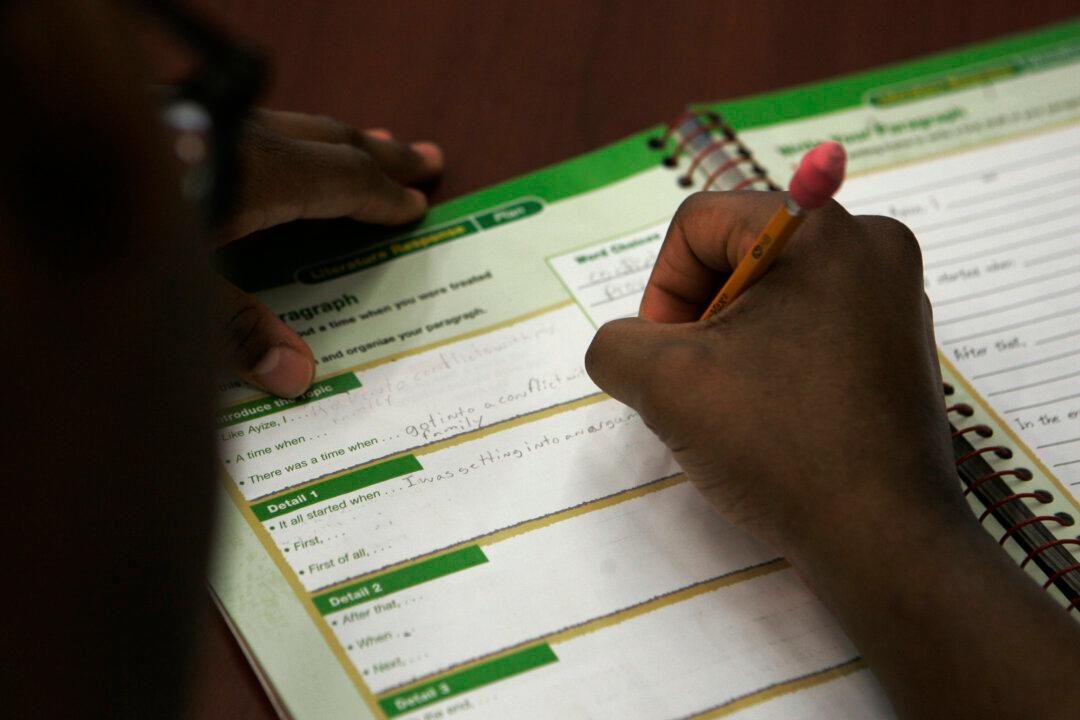

Guards in the Ohio juvenile system are now called “youth specialists,” and school uniforms have replaced prison khakis. Offenders spend their days in a school setting and earn their high school diplomas.