NEW YORK—New York City is preparing to end its ban on cellphones in schools, dooming an industry that sprang up near dozens of schools where teens could park their phones in a van for a dollar a day.

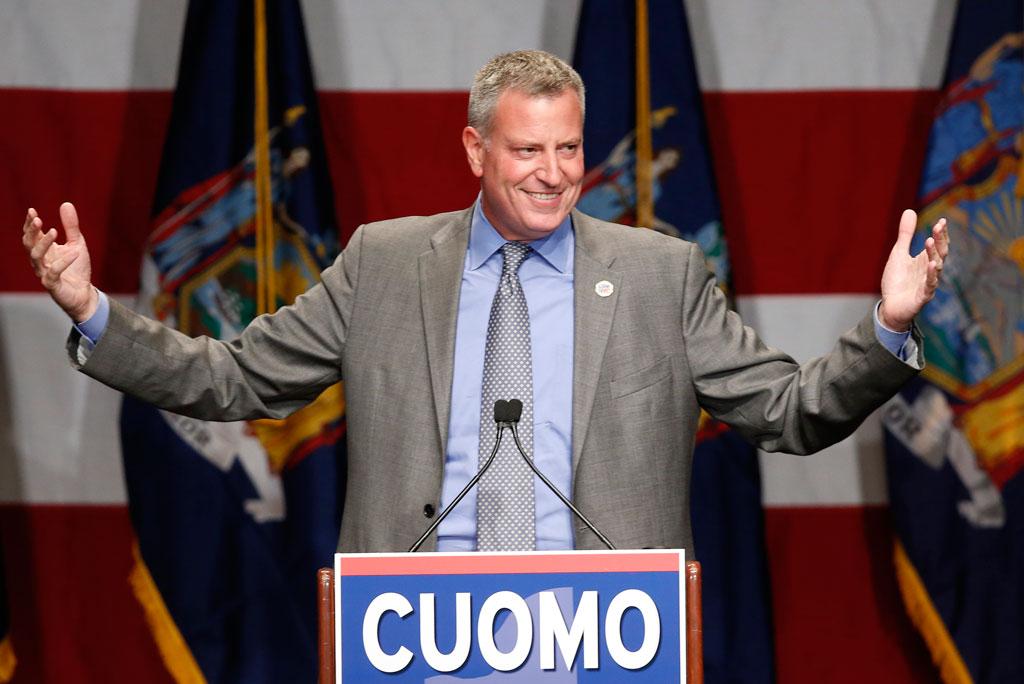

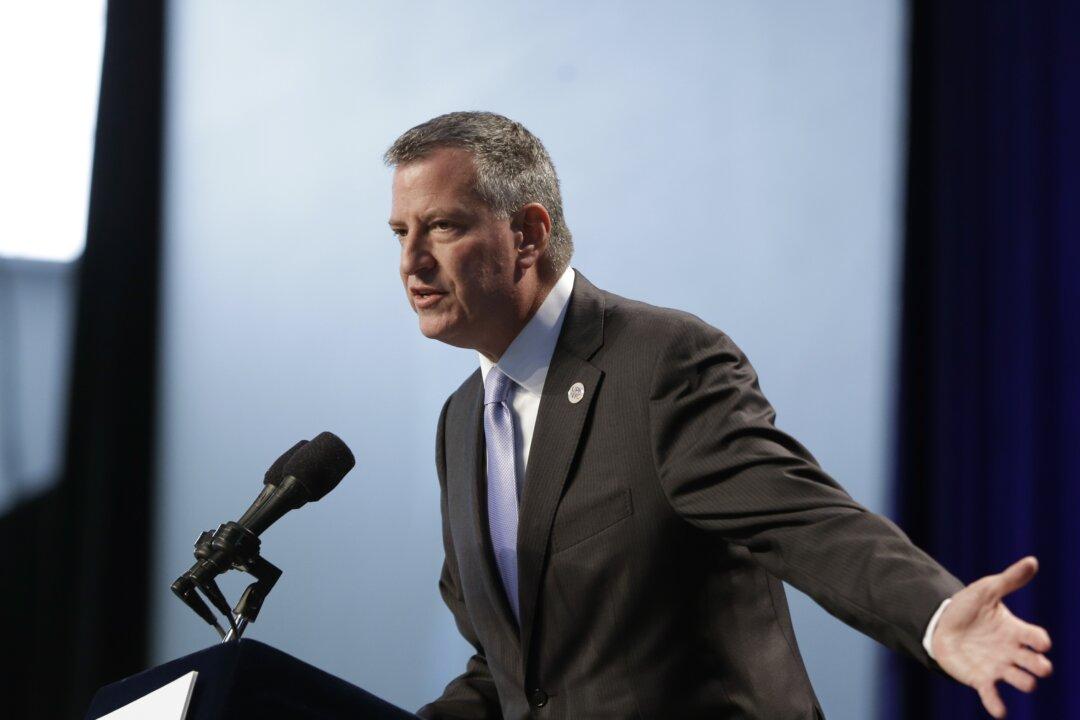

Mayor Bill de Blasio—apparently the first mayor to have a child in New York City public schools while in office—promised to end the ban during his campaign and acknowledged last month that his own son brings a phone to Brooklyn Technical High School.

He gave no date for ending the ban but said that for parents it’s “very, very important to know how to reach their kids.”

The out-of-sight, out-of-mind rule is already the de facto policy at most New York City high schools including Brooklyn Tech, where Dante de Blasio is a senior. Even with the phone ban still on the books, students at those schools are told with a wink, “If we don’t see it we don’t know about it.”

But at the 88 city school buildings where metal detectors have been installed to keep weapons out, the ban is strictly enforced because the scanners catch phones too.

Students at schools with metal detectors must either leave their phones at home or shell out for storage. For those students, many of whom have spent hundreds of dollars to store phones and other gadgets over their high school careers, the ban can’t end soon enough.

“This costs a dollar every day and it’s a pain to get in that line just so I can get my phone back so I can go home,” 16-year-old Adam Scully said after retrieving his phone from the bright blue Pure Loyalty Electronic Device Storage van parked outside the Washington Irving High School complex near Manhattan’s Union Square.

Adam said leaving his phone at home is not an option, adding, “It’s not because I’m overly attached to my phone. It’s because my mom might need to contact me.”

Parents of teens who attend schools with metal detectors said they too would welcome an end to the phone ban.

Walter McIntyre, who has two children at Clara Barton High School in Brooklyn, said he currently drives his children to school and holds on to their phones during the school day—even though many of their classmates leave their phones in a van.

“They don’t trust them in those places,” McIntyre said. “They don’t want to lose their phones because they know they’re not getting another one.”

The security issue came to the fore when a Pure Loyalty van was robbed in the Bronx in June 2012 and hundreds of students lost their phones.

Advocates urged then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg to end the phone ban after the robbery but he stood firm.

De Blasio said he had other priorities after taking office Jan. 1 such as expanding access to pre-kindergarten. But he promised that the phone ban would end soon.

City education officials said they are formulating a policy that includes sanctions against using a phone to cheat as several dozen students at the selective Stuyvesant High School did in 2012, forcing the principal into retirement.

A policy that allows phones inside a school but tells students to keep them stowed during class will bring New York in line with other large school districts such as Los Angeles, Chicago, and Atlanta.

Going Out of Business

The phone-storage operators, who saw a need and created an industry unique to entrepreneurial New York, said they know their days are numbered.

“There'll be a lot of people who will not be working. That’s never a good thing,” said David Perez, a Pure Loyalty employee who answered the phone at the number painted on the company’s vans.

Pure Loyalty was started in 2010 by correction officer Vernon Alcoser, who has since sold the business.

A Pure Loyalty split-off known as UCT operates a van parked outside the Norman Thomas High School complex, where teens retrieve their phones in the shadow of the Empire State Building.

Asked about the cellphone ban’s demise, a man who answered at the number on the van but wouldn’t give his name said, “It’s going to put me out of business but what can I do?”

From The Associated Press