NEW YORK—In a city piled high with ambitious architecture, a seven-floor structure off the beaten path boasts a distinction of its own: It’s billed as the first multistory, modular-built apartment building to open in the nation’s apartment capital.

Called the Stack, the building near Manhattan’s northern tip aims to show that while stackable apartments can save builders time and money, modular doesn’t have to mean monotonous. Its chunky front embraces its building-block roots, but the apartments’ interiors defy their boxy components with varied floor plans and stylish fixtures and finishes.

Modular construction—assembling a building from prefabricated sections instead of building from scratch on-site—has been around for decades, but interest has grown recently around the country and in its biggest city. The world’s tallest modular building, a 32-story apartment tower, is rising in Brooklyn.

Advocates said modular building can trim costs and timetables—module factories don’t have to worry about bad weather—and make construction more consistent. Still, the technique presents special challenges (say, driving a 750-square-foot box over the George Washington Bridge), and not all projects have proven speedy. Some have faced pushback from labor interests, not to mention an image problem: The method is sometimes perceived as cheap and, well, cookie-cutter.

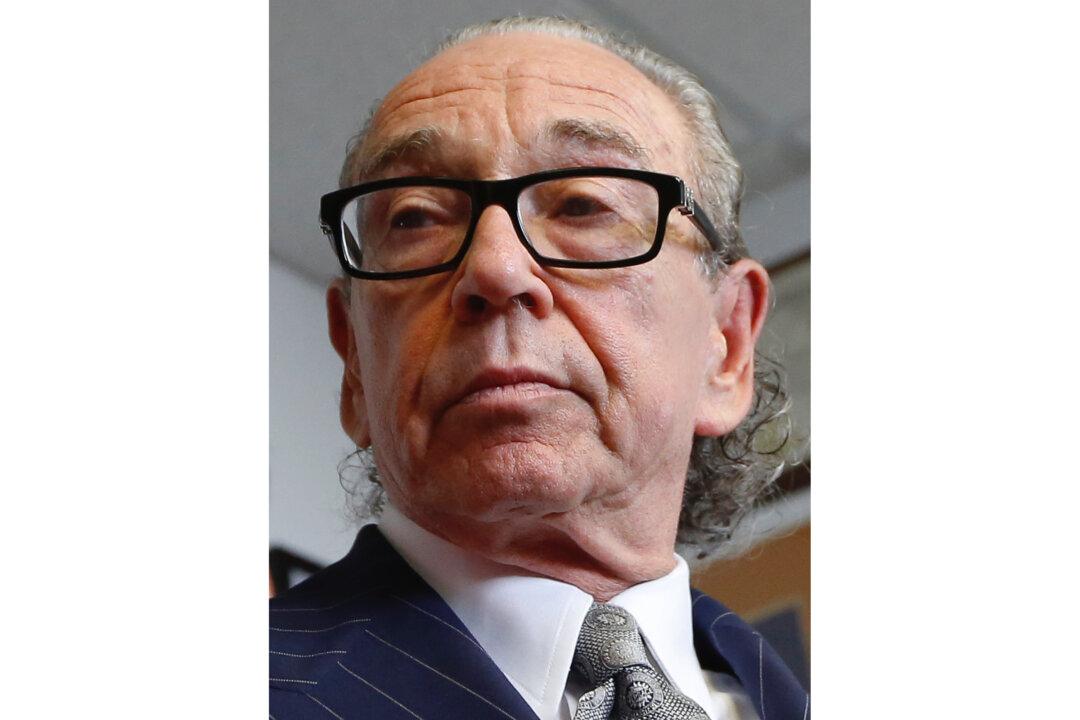

“‘Pre-fab’ and ’modular' have somewhat of a stigma associated with it, in some people’s minds, whether it’s appropriate or not,” developer Jeffrey M. Brown said. But “this approach can really produce cool buildings.”

Some key facts about modular buildings (in stackable form):

The Lay of the Land

Modular apartment buildings date at least to Montreal’s Habitat 67 complex, built for the 1967 World’s Fair and still a desirable address. Section-stacking construction is still relatively rare in the United States: about 1 percent of the overall market outside single-family homes, according to the Modular Building Institute, a trade association. But interest has grown in the last 20 years, as some developers embraced the efficiency of piecing together components that come complete with floors, electrical systems, appliances—even towel bars—to create apartments, hotels, hospitals, and more. New York City’s Department of Buildings said 39 modular projects have at least submitted paperwork.

How the Stack Works

The 28 apartments were formed from 59 modules. The rectangular components are all 12.5 feet wide and 50 feet to 60 feet long, but with different interior walls, doorways, and other attributes. The modules sit roughly side-by-side, but their interior layouts interlock like jigsaw puzzle pieces to form apartments of various sizes and configurations, featuring large windows, stylish fixtures, and sometimes terraces.

Building the Stack

Construction began in fall 2012 after years of planning by Brown, co-developer Kim Frank and architecture firm Gluck+. The foundation, basement, and first floor were conventionally built, while DeLuxe Building Systems made the steel-framed modules in Berwick, Pa. Trucked four per night over the George Washington Bridge, they were lifted into place and fastened to one another in 19 days. It took months to hook up mechanical systems, attach facade panels, and secure final approvals. Brown estimates he saved about six months of conventional construction time and 15 to 20 percent of the roughly $7 million construction costs. (The overall cost was $13 million, including land and other expenses.)

Living in the Stack

Except for six designated affordable apartments, studios start at about $1,600 a month, three-bedrooms at $3,700. That’s on the high side for its far northern Manhattan neighborhood, where real estate listings show a number of one-bedrooms for rent in the $1,300 to $1,800 range. Brown said the Stack is “providing an option” that’s unusual in the venerable neighborhood. Some apartment hunters apparently agree: 60 percent of the units were rented within about a month, he said.

What’s Next?

Among New York’s next modular moves is a Manhattan “micro-unit” apartment building plan that won a city contest last year; the project is underway. And the pioneering 32-story, 363-apartment “B2” is under construction as the first residential tower in the massive Atlantic Yards development, which includes the Brooklyn Nets’ arena.

B2 is due to be finished in late 2015—more than a year after initially projected. It took considerable time to set up a factory at the nearby Brooklyn Navy Yard to make the modules, said Joe DePlasco, a spokesman for Atlantic Yards developer Forest City Ratner. The modular method also spurred some construction trade groups to sue the city for not requiring certain licenses for workers at the module factory; the suit was dismissed. After taking heat from officials over the pace of creating housing at Atlantic Yards, Forest City has decided to build the next two apartment towers conventionally.

Modular isn’t magic for every project, said Tom Hanrahan, the dean of architecture at New York’s Pratt Institute, but it has its place—one where “you can repeat it and stack it.”

From The Associated Press