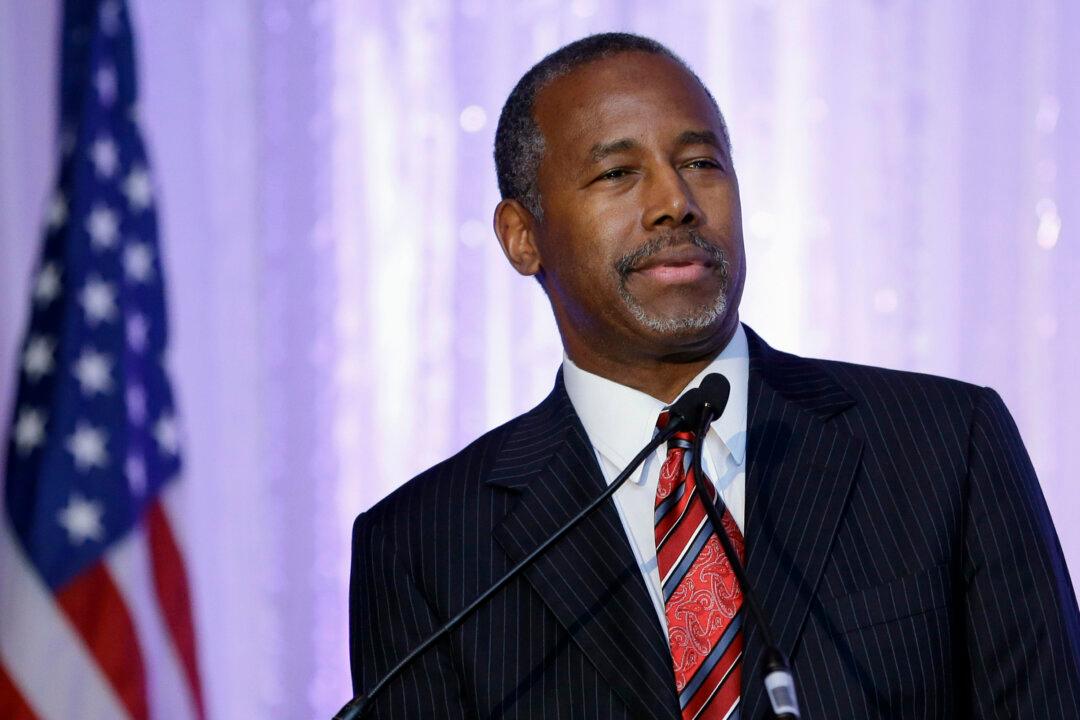

PALM BEACH GARDENS, Fla.—Ben Carson rose to top the Republican ranks of White House hopefuls as the wise outsider—a candidate without any experience in office, but one who offers a compelling personal narrative, speaks openly of his deep Christian faith and issues calm-but-tough indictments of the nation’s leaders.

Now, just as he finishes a triumphant, monthlong book tour, Carson finds that persona threatened by a series of inquiries that cast doubt on the veracity of his biography.

While Carson may be an unorthodox candidate running an unorthodox campaign, scrutiny of his past is par for the course for would-be presidents. But in a race in which an angry electorate has scrambled the established order in the Republican Party, the retired neurosurgeon predicts what he calls a “witch hunt” will only help him with voters.

“There’s got to be a scandal. There’s got (to be) some nurse he’s had an affair with,” a defiant Carson said Friday night of the hopes of those looking into his past. “They are getting desperate. Next week, it will be my kindergarten teacher who said I peed in my pants. It’s ridiculous.”

Carson has every reason to expect that what for almost any other candidate would be considered negative attention will help him. While he’s long used extreme examples to make his case, including repeated references to such third-rails as Nazi Germany and slavery, he’s emerged as one of the GOP field’s best fundraisers and sits atop numerous preference polls.

“We’ve obviously had a variety of controversial statements,” admitted Doug Watts, Carson’s campaign spokesman. “Sometimes you just flip a coin as to how people will react to them.”

That is the obvious question to the latest development in Carson’s rise—a whirlwind week in which one new question about Carson’s background was followed by another.

CNN reported it could not find friends or confidants to corroborate his story, told as part of his widely read autobiography, “Gifted Hands,” of unsuccessfully stabbing a close friend when he was a teenager. A story published by Politico examined his claim of having received a scholarship offer to attend the U.S. Military Academy. The Wall Street Journal said it could not confirm Carson anecdotes from his high school and college years.

There are others. Last month, police in Baltimore said they didn’t have enough information to verify Carson’s account of being held at gunpoint at a fast-food restaurant in the city. In the third GOP debate, Carson said it was “absolutely absurd” to say he had a formal relationship with the company Mannatech. He is featured in the company’s videos, including one from last year in which he credits the firm’s supplements with helping people restore a healthy diet.

Carson and his campaign forcefully reject any suggestion he has been less than completely truthful. Indeed, Friday’s news conference may have been the first instance of the 2016 campaign in which the notably even-tempered Carson showed open signs of anger.

During a combative 20 minutes, Carson said the media hadn’t subjected President Barack Obama to the same level of scrutiny he now faces and demanded the reporters present explain why. He said he would think about revealing the name of the person he has said he tried to stab, but only if reporters would sign an affidavit promising to “sing my praises” for doing so.

“Will you do that? Yes?” Carson asked. “My job is to call you out when you’re unfair, and I’m going to continue to do that.”

Carson’s advisers say they are determined to keep their attention focused on the campaign as he shifts from his recent book tour—an ostensibly noncampaign exercise paid for mostly by his publisher—to more traditional voter outreach in Iowa and other early voting states.