News Analysis

In just several months, the grass-roots Arab Spring uprisings that began in late 2010 achieved more politically than terrorist group al-Qaeda had over its entire history. It sent a clear message that nonviolence is a more effective route, both in gaining support among the populace, and in achieving political goals.

The fallout from the Sept. 11 attack on the U.S. Embassy in Libya showed the clear difference between the old ways of terror, and the new mentality that arose from the Arab Spring. Just 10 days after the attack, tens of thousands of Libyans marched to the Benghazi base of militant Islamist group Ansar al-Shariah, which they blamed for the attack, and drove them out of town.

“Terrorism is a spectacularly unsuccessful tactic,” said Steven Pinker, professor of psychology at Harvard University, via email. Pinker is also author of “The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined.”

Pinker has shown through research that the world as a whole seems to be moving away from violence. A key reason behind this shift, he says, is “The logic of violence is ‘If you don’t give me what I want, I will hurt you,’” said Pinker. “However, the target of the threat also has to believe the converse: ‘If you do give me what I want, I will not hurt you,’ otherwise there’s no point complying with the threat.”

Use of violence, ironically, is the factor that prevents terrorism from truly achieving any goal. According to Pinker, it leads the public to believe terrorist groups “are only interested in destruction, not in constructive negotiation, so they support all-out measures that will stamp the terrorists out.”

History shows this. The Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the twin towers led the United States to increase its troop presence throughout the Arab world and toppled al-Qaeda’s stronghold in Afghanistan. Following the recent Sept. 11 attack in Libya, the United States assigned FBI agents to find the responsible parties, with Special Operations forces and drones on standby.

Pinker added to the list of historical examples of unrealized terrorist goals. “Israel continues to exist, Northern Ireland is still a part of the United Kingdom, and Kashmir is a part of India,” Pinker said.

“There are no sovereign states in Kurdistan, Palestine, Quebec, Puerto Rico, Chechnya, Corsica, Tamil Eelam, or Basque Country,” he said. “The Philippines, Algeria, Egypt, and Uzbekistan are not Islamist theocracies; nor have Japan, the United States, Europe, and Latin America become religious, Marxist, anarchist, or new-age utopias.”

Terrorism was, nonetheless, once widely regarded as a rational response to achieve a political goal.

This was the view at the time of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. The spread of communism relied heavily on violent revolutions, and prior to that, the break from colonialism was also violent.

But the world is changing.

Erica Chenoweth, director of the Program on Terrorism and Insurgency Research at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies, has shown through research that violence is increasingly becoming less effective as a political tactic—and that governments established through nonviolent means are more likely to move toward democracy and less likely to fall into civil war.

Chenoweth shows the drastic shift from violent to nonviolent campaigns since 1940, in her book, co-authored by Maria Stephan, “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict.”

Charting statistics over the course of decades, Chenoweth and Stephan show that in the 1940s and 1950s the success rate of violent campaigns was about the same as nonviolent campaigns. This began changing in the 1960s, however, and violent campaigns became less successful. The success rate of nonviolent campaigns outdid that of violent campaigns by nearly seven-fold by the 2000s.

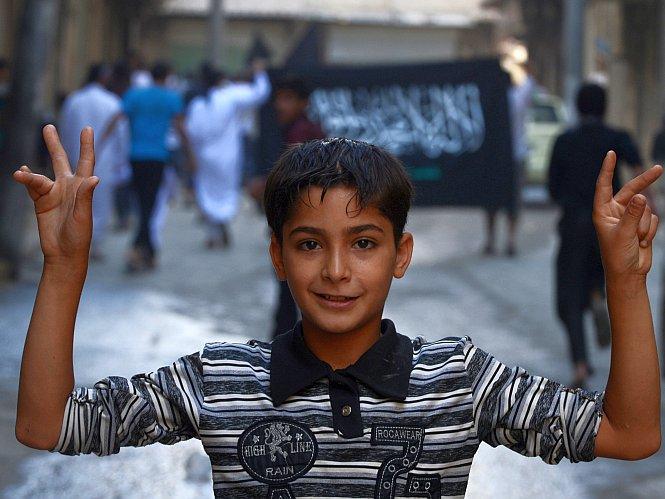

The Arab Spring is a good example of the trend shown in their research. “The mass civilian participation in a nonviolent campaign is more likely to backfire in the face of repression, encourage loyalty shifts among regime supporters, and provide resistance leaders with a more diverse menu of tactical and strategic choices,” state Chenoweth and Stephan in the book.

Max Abrahms, terrorism expert and fellow at John Hopkins University, has done extensive research on the effectiveness of terrorism. He said in a phone interview that not only has terrorism been politically ineffective, but “rather than inducing government concessions, terrorist attacks tend to elicit the opposite response—harsh government countermeasures.”

Abrahms, like Pinker, concludes that terrorism is so ineffective mainly because its foundation in violence makes terrorist groups appear too extreme to negotiate with.

The recent incidents in Libya, Abrahms said, suggest that broad support for terrorism is failing and “perpetrators of violence—particularly in international affairs—are starting to recognize its political ineffectiveness.”