Is it possible to equitably divide the planet’s resources between human and non-human societies? Can we ensure prosperity and rights both to people and to the ecosystems on which they rely?

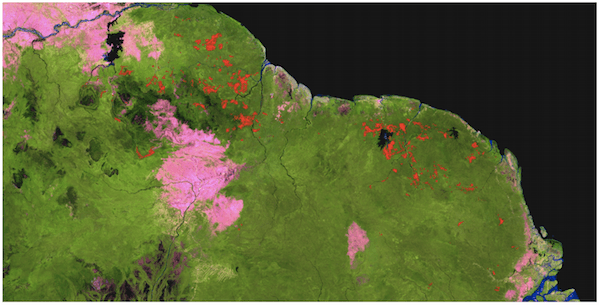

In the island archipelago of Indonesia, these questions become more pressing as the unique ecosystems of this global biodiversity hotspot continue to rapidly vanish in the wake of land conversion (mostly due to palm oil , poor forest management and corruption).

For 22 years, Dr. Erik Meijaard has worked in Indonesia. Now, from his home office in the capital city, Jakarta, he runs the terrestrial branch of an independent conservation consultancy, People and Nature Consulting International (PNCI).

“I think conservation in general is doing really badly in countries like Indonesia,” Meijaard told mongabay.com. “The few examples of conservation that did work in Indonesia are pretty much all outside the protected area framework. We need to step away from the present framework of government-managed protected areas, and start piloting alternative approaches, like privatization of conservation management, including revenue taking.”

Meijaard has an academic background in tropical ecology and a PhD in biological anthropology. His academic work focuses on the evolutionary history of the mammals and trying to understand what that means for their conservation. During his first years in Indonesia, he traveled through remote parts of Borneo and Sumatra mapping the distribution of orangutans and other large mammals to develop the first spatial datasets for these species.

Erik has worked for several international NGOs and research organizations including The Nature Conservancy Indonesia’s, WWF-Netherlands and the Center for International Forestry Research, where he was instrumental in the development of new conservation strategies and initiatives, including developing the original concept for the Heart of Borneo project for WWF-Netherlands.

Currently, Meijaard spends most of his time on the Borneo Futures initiative. The Borneo Futures initiative is a Borneo-wide program that, according to Meijaard, “seeks to support a paradigm shift in how decisions are made for land, forests and natural resources…. to base decisions on a full consideration of short- and long-term consequences for local communities, ecosystem services and biodiversity.”

Meijaard is also a science communicator and contributing blogger to mongabay.com.

An Interview with Dr. Erik Meijaard

Mongabay: What is your background?

Erik Meijaard: I first came to Indonesia in 1992, and my work has always focused on this part of the world. My scientific background is in tropical ecology and mammal taxonomy. But over the years I have expanded my work into different directions all related to tropical conservation science and management. This includes social studies, economics, spatial sciences, forest management science, wildlife management, policy, evolutionary studies, and also broader research on the functioning of conservation.

Mongabay: How long have you worked in tropical forest conservation and in what geographies? What is the focus of your work?

Erik Meijaard: See above. Presently I allocate most of my time to the Borneo Futures initiative. This is a Borneo-wide program that seeks to support a paradigm shift in how decisions are made for land, forests and natural resources, i.e. to base decisions on a full consideration of short- and long-term consequences for local communities, ecosystem services and biodiversity. The initiative started in 2011 and originated from an influential think tank organized by the Arcus Foundation, a conservation NGO based in Cambridge, UK and in the USA and the principle funding partner of the Borneo Futures initiative. Combined with further support obtained from UNEP, and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions, this has enabled the network to grow to more than 50 associated scientists and NGO representatives.

Mongabay: Are you personally involved in any projects or research that represent emerging innovation in tropical forest conservation?

Erik Meijaard: What we are trying to do in Borneo is innovative both because of the scale and transnational scope of the project, but also because of its all-encompassing science approach. At the moment, most land use decision-making in Borneo is based on understanding of short and medium-term economic gains. It is clear that replacing a degraded forest area with an oil plantation generates significantly more revenues for the company and government, from which also local communities benefit. The costs of such decisions however are rarely considered, although the impacts of deforestation are clearly felt by many. Especially the loss of ecosystem services should not be ignored. Temperature increases related to deforestation, increased flooding, siltation of rivers, and other factors have real negative impacts on local people and economies. What we are doing in our Borneo Futures work is making those costs and benefits explicit and through land use optimization analyses develop alternative future scenarios for Borneo’s land use. In this, we also make use of extensive spatial data on how local people perceive forests and forest services, and what the legal requirements actually are for maintaining forests. These analyses should give policy and decision-makers a much more comprehensive insight into the longer-term impacts of particular land use decisions. In democratic countries it also provides potentially affected communities with an informed voice and choice allowing them (at least theoretically) to push their political representatives to steer land use decisions in a certain direction.

Mongabay: What do you see at the next big idea or emerging innovation in tropical forest conservation? And why?

Erik Meijaard: I think what we do not at all have an answer to is how this planet is going to feed 11 billion people in a few decades from now, most of which will aspire to a level of welfare and well-being presently enjoyed by much of the western world. Where are the required resources going to come from and are they sufficient? If not, how is it then decided who will be the haves and have-nots? I guess we are somehow hoping for techno-solutions varying from agricultural miracle plants, to replacing fossil fuels with biofuels, but I think that there are plenty of reasons not to be too optimistic about these alternatives. The consequences for wildlife conservation are likely to be severe but we are not ready at all to think that far into the future.

Conservation is all about crisis management and today’s crisis is bad enough, so let’s not even think about the challenges in 50 years. But, in a way, we need to do that too and come up with answers on how the planet’s resources are going to be divided up between human and non-human societies, and how this will be done on an equitable basis. This will require a level of international cooperation on environmental decision-making that is largely non-existent. Maybe new legal frameworks are needed which guarantee certain minimal rights to ecosystems that are of importance to all people. Ongoing collaborations on reducing the impacts of global climate change are part of that, as are international collaboration on combating wildlife trade. But much more is needed and efforts to build up these new frameworks need to be started now.

Mongabay: In regards to conservation, is there anything you feel is NOT working (or not working well) that continues to get a lot of attention and support?

Erik Meijaard: I think conservation in general is doing really badly in countries like Indonesia. Protected area status is all but meaningless. National parks lose their forest at the same rate as logging concessions. Local people who I ask about the protected areas they live next to say that to them it is a meaningless concept and that protected areas might as well not be there. They largely ignore any of the rules and regulations associated with protected areas. The Indonesian government needs to realize this major weakness and consider alternatives. The few examples of conservation that did work in Indonesia are pretty much all outside the protected area framework. There, local communities, local government or other groups take the lead in conservation. Unlike the government, these do show much more commitment and ability to effectively implement conservation management. We need to step away from the present framework of government-managed protected areas, and start piloting alternative approaches, like privatization of conservation management, including revenue taking.

This article was originally posted at news.mongabay.com