In the Brazilian Amazon, deforestation alerts are being submitted via smartphones. On the ground technicians send alerts to a database stored in “the cloud.” This information is added to maps, which, along with satellite imagery, are used to inform law enforcement. And the speed of this process is getting real results.

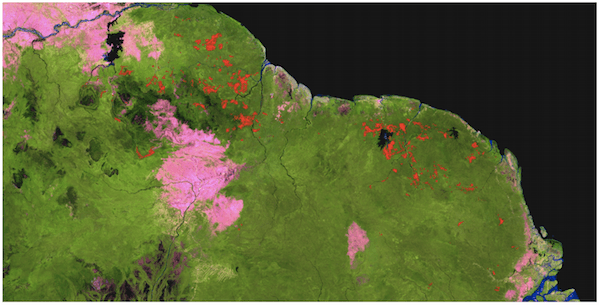

Since 1992, Dr. Carlos Souza Jr. has worked for the Brazilian NGO Imazon. Currently, he coordinates Imazon’s Amazon Monitoring Program, the first non-governmental deforestation alert system for the Brazilian Amazon. Souza uses spatial analysis to identify priority conservation areas in the Amazon and to map carbon stocks of forests. He develops remote sensing techniques to monitor and map land cover and land use changes, particularly forest degradation caused by selective logging, fires and fragmentation.

“Monitoring and reporting deforestation statistics every month helps to keep the general society and authorities informed and track the target to reduce deforestation,” Souza told mongabay.com. “It is now like monitoring inflation in the country: people pay attention national wide every month to deforestation statistics.”

Souza became a Senior Researcher of Imazon in 2001 and was the executive director of the institute from 2005 until 2008. He is a member of the Global Observation of Forest Change and Land Cover Dynamics and has served as Leader of the Avina Foundation since 2008. Souza has over 75 listed publications, and in 2010, was awarded the Skoll Award on Social Entrepreneurship.

“I think a promising big thing [in tropical forest conservation] is crowdsourcing monitoring using mobile technology. We have now the potential to have millions of people tracking changes on our planet and quickly inform the global society for rapid response,” Souza said.

INTERVIEW WITH CARLOS SOUZA JR.

Mongabay:What is your background? How long have you worked in tropical forest conservation and in what geographies? What is your area of focus?

Carlos Souza Jr.: I received a bachelor degree in geology and became a geographer during my Ph.D. training. Over the past two decades, my research has focused on the development of remote sensing techniques to monitor tropical forests and on spatial analysis to identify anthropogenic threats to forests and areas for forest conservation. I conduct my research mainly in the Brazilian Amazon and have collaborated with other researchers in other tropical forest regions in the Pan-Amazon region, in Africa and in Southeast Asia.

Mongabay:Are you personally involved in any projects or research that represent emerging innovation in tropical forest conservation?

Carlos Souza Jr.: Yes, right now I am working on two projects related to forest conservation linked to other relevant issues: food security and climate change.

The first project is the development of a land traceability system based on geospatial and remote sensing technologies for tracking agroforestry production. The global demand for food will increase and monitoring agricultural lands, in terms of their productivity, environmental and law compliances, and the potential expansion of crops over forested regions are important tasks to inform and educate consumers and policy makers.

The second project is mapping areas for forest restoration that is also linked to agricultural lands and has great potential to carbon sequestration. For that, we have identified priority areas for forest restoration in the state of Pará (Brazil) aiming at reducing landscape fragmentation, mitigating soil erosion and protecting water paths and habitat for biodiversity, and as well as to comply with the new Brazilian Forest Code. All these issues are linked to tropical forest conservation and food security, which together with climate change represent big challenges for the next decades.

Mongabay:What do you see as the biggest development or developments over the past decade in tropical forest conservation?

Carlos Souza Jr.: I can say that reducing deforestation, while keeping the economy and the agriculture production growing in Brazil, was one of the biggest accomplishments, saving forests and significantly reducing CO2 emissions. This required a multi-institutional approach with governments, from federal to local levels, civil society and private sector working together. Monitoring and reporting deforestation statistics every month helps to keep the general society and authorities informed and track the target to reduce deforestation. It is now like monitoring inflation in the country: people pay attention nationwide every month to deforestation statistics.

Mongabay:What’s the next big thing in forest conservation? What approaches or ideas are emerging or have recently emerged? What will be the catalyst for the next big breakthrough?

Carlos Souza Jr.: I think a big promising thing is crowdsourcing monitoring using mobile technology. We have now the potential to have millions of people tracking changes on our planet and quickly inform the global society for rapid response. And of course the catalyst for this is the Internet. This technology can also help building more transparent supply chain systems that, as a result, can lead to better environmental conservation approaches. This movement can take forest conservation outside the boundaries of parks and conservation units and include farms in the process.

Mongabay:What isn’t working in conservation but is still receiving unwarranted levels of support?

Carlos Souza Jr.: There are many successful projects on forest conservation in every country in the world, conducted by local traditional communities, schools, corporations, conservation units, and cities, and many other segments of our society. The challenge for the next decade is scaling up the successful conservation initiatives to revert global pressuring problems, such as biodiversity loss, global warming, soil depletion, and desertification, among other issues. There are many things that are working but need to receive global attention —this means we have to think really big!

This article was originally written and published by Liz Kimborough, a contributing writer for news.mongabay.com. Please visit their website for the original story and more information.