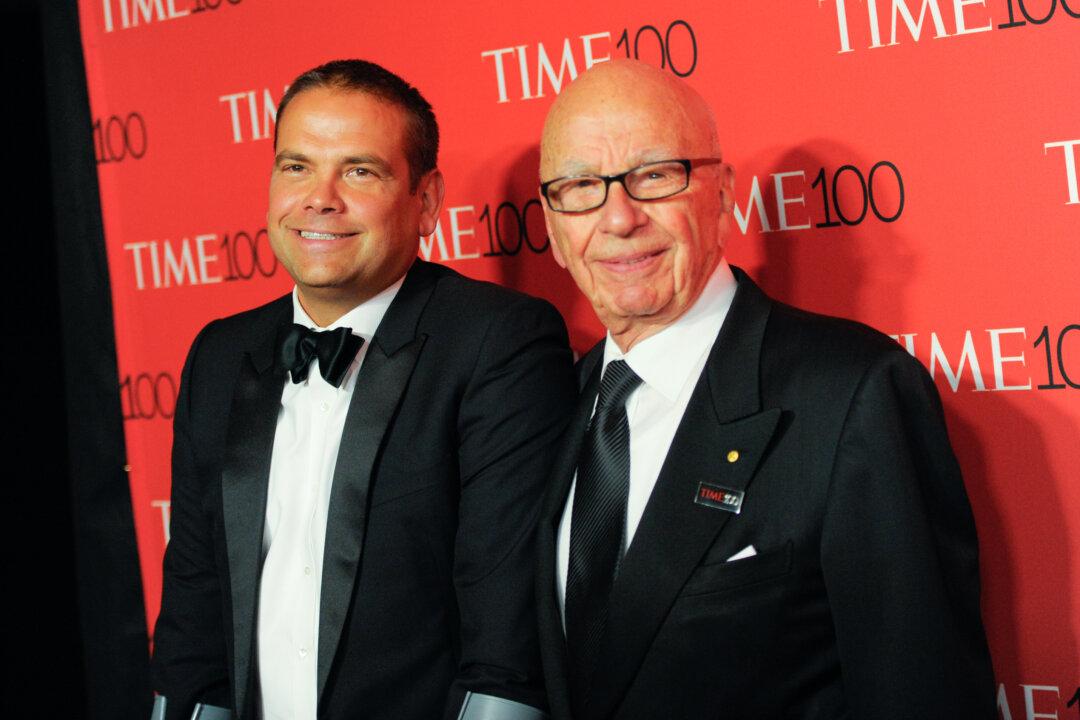

I’ve been teaching students in Hong Kong about the relationship between politics and the media, and wanted to illustrate the sometimes problematic relationship between media and power. So I showed them Robert Peston’s BBC Panorama documentary about the “industrial-scale” criminality of Rupert Murdoch’s U.K. red-tops in the era of Andy Coulson and Rebekkah Brooks (on Friday, Aug. 28, Rebekkah was named as CEO for News Corp in the U.K.).

Like most people with even a passing interest in the part played by News Corporation in British politics, I remember exactly what I was doing when the scandal broke in 2011 and the sense of a seemingly indestructible media behemoth crumbling into chaos and ruin before our eyes. I had been researching and teaching about the News empire for more than two decades by then, frequently using it as a case study of how at least some privately owned media organizations abuse their power in pursuit of competitive success and political influence.

While I always took care to acknowledge Murdoch’s positive contribution to sustaining the idea that journalism is important and must be invested in if it is to survive the digital age, the deeply unethical behavior of The Sun in relation to such events as the Hillsborough stadium disaster and the sinking of the Belgrano during the Falklands War were and remain classic examples of the excesses of British tabloid journalism.

Murdoch’s use of his media to influence and shape the democratic political process in all the markets where he operates was illustrated by reference to Fox News, The Sun and other News Corp outlets which operate as what the late newspaper proprietor Robert Maxwell called a “megaphone” for the Murdochian world view and political agenda.

So the phone hacking scandal of 2011 was a genuinely shocking thing to behold.

Peston’s documentary was a reminder of that moment, which at the time was generally regarded as pivotal in British political history. Where senior politicians of both Labor and Conservative parties had for decades “queued up to kiss the shoes” of Rupert Murdoch and his tabloid editors (as investigative journalist Nick Davies put it to Peston), suddenly no–one wanted to be his friend anymore.

The hitherto unspoken truth (unspoken among politicians who were its beneficiaries, that is) that the relationship between the Murdoch media and the political elite in Britain had become undemocratic and incestuous became the new common sense overnight.

Among the many adverse impacts of the scandal on News Corporation was the collapse of its bid to buy the remaining 61 percent of the shares for BSkyB that it didn’t own—a deal that was by now attracting heat for both the Murdochs and a government that had seemed eager to wave the multi-billion deal through despite massive public opposition.

There was talk of prosecutions in the United States, where corporate criminality such as the bribery of public officials is taken very seriously. That never came to pass, but few doubted that the reputation of Rupert Murdoch and the corporate culture which he had presided over for more than 40 years had been seriously—perhaps terminally—wounded.

Rupert Resurgent

That view has turned out to be well wide of the mark. Once again News Corporation is on the offensive against its old enemy, the BBC, lobbying a second-term Cameron government—armed now with a majority in the House of Commons and thus empowered to act with greater freedom than was possible in the five years of coalition—to shrink the corporation.

Once again there are reports of Murdoch’s privileged access to the corridors of power, as in The Independent in July:

“George Osborne is under pressure to reveal if he held a private meeting with Rupert Murdoch days before the Treasury imposed a £650m budget cut on the BBC. Whitehall speculation about the alleged meeting—which would raise fresh questions about the closeness of the relationship between the Conservatives and the Murdoch empire—has prompted Labor to write to Mr. Osborne demanding he release full details of his contact with the News Corp boss.”

It looks like business as usual, then, for a global media baron used to commanding the attention of political leaders and wielding his power to influence policymaking on the future of the BBC.

Whose Side Are You On?

In Australia, where I live and work—and where the phone-hacking scandal had little impact on News Corporation’s activities—a similar offensive is underway against the ABC.

In Australia, as in the U.K., News Corporation is allied to a right-of-center government which regards the public sector in general, and public service media in particular, as hostile to its goals and ripe for “reform”.

The Australian, News Corp’s flagship title down under (like The Times and Sunday Times in the U.K.), maintains a steady flow of anti-public service media reportage and commentary, criticizing with boring predictability executive salaries, or the alleged bias of its news department, or indeed anything that can be made to appear excessive and un-Australian.

After the Zaky Mallah affair, Prime Minister Tony Abbott asked of the ABC: “whose side are you on?” In a similar way, News Corporation likes to present the ABC as a cultural fifth column, its commentators regularly demanding that it be reduced to a “market failure” broadcaster—and in the process, coincidentally enough, allowing News the opportunity to become even more dominant in the Australian media landscape than it already is.

On this issue, as on many others, Murdoch’s media act as cheerleaders for the Abbott government.

I’m not a conspiracy theorist, but the ferocity of the campaigns against public service media in Australia and the U.K. could easily be read as more than coincidence. In both countries News Corp press seek to undermine the funding models of public service media, and their right to produce popular entertainment programming such as The Voice. This has been a decades long campaign for News Corp in the U.K., and after the Jimmy Savile scandal and other dents to its reputation, the BBC is more vulnerable than it has ever been.

The ABC, one might argue, is in a stronger defensive position than the BBC. While the latter now faces five years of majority Conservative government, Abbott must go to the polls in September 2016 at the latest—and repeated opinion polls show a deep affection among Australians for the ABC.

Tampering with Auntie would be politically risky. The real danger will come if the Coalition is re-elected with a comfortable majority, giving Abbott the freedom of maneuver now enjoyed by Cameron in the U.K.

In the meantime, the BBC and ABC must hold their nerve, and trust in the capacity of the publics they serve to continue recognizing the importance of the role they play and the excellent value for money which they deliver. Both the BBC and ABC cost the individual license fee or taxpayer much less than a subscription to Foxtel or BSkyB. Even the purchase of one daily newspaper in either country for a year exceeds the cost per person of funding public service media and the wealth of content they deliver on TV, radio and online.

Supporters of public service media are familiar with these arguments, but in both Australia and the U.K. they must be made and made again, forcefully and with confidence.

To lose the BBC and the ABC, or to see them reduced to a pale shadow of public service media—think PBS and NPR in the United States—would be a cultural disaster from which there would be no recovery that was not directed by News Corporation and other private media interests.

Brian McNair is a professor of journalism, media, and communication at the Queensland University of Technology, Australia. This article was previously published on TheConversation.com