NEW YORK—The New York Times for nearly six months has been preparing a hit piece against Shen Yun Performing Arts, The Epoch Times has learned.

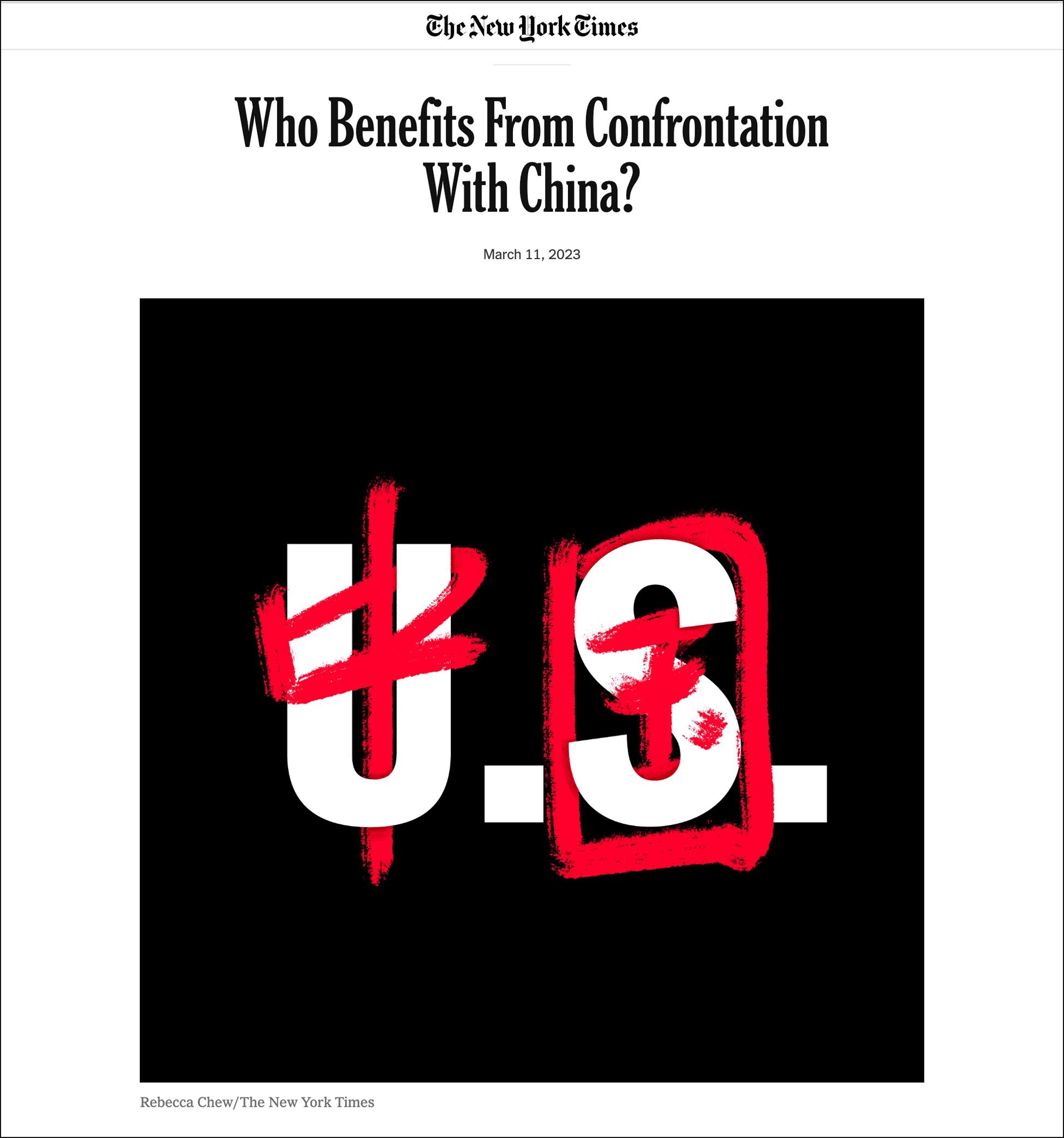

Communications obtained by The Epoch Times suggest the article, which is yet to be published, will play into the hands of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in its transnational repression campaign against the performing arts company.

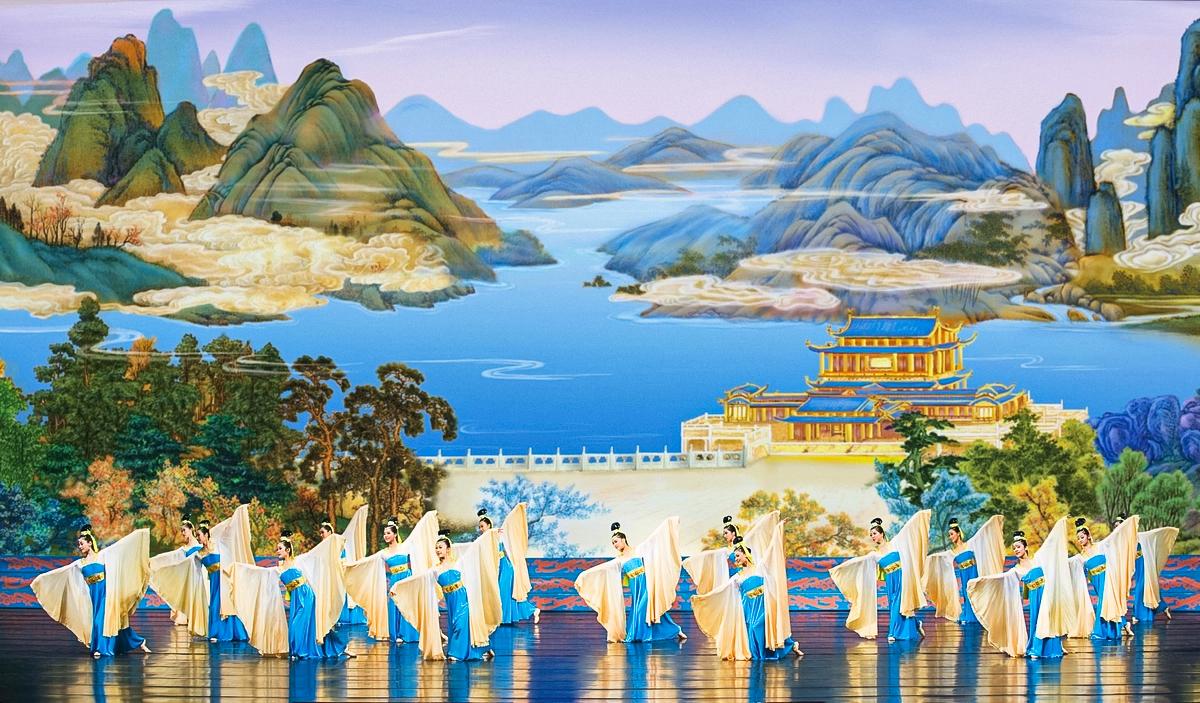

The New York-based Shen Yun, whose mission is to revive traditional Chinese culture and whose slogan is “China Before Communism,” has been a major thorn in Beijing’s side for nearly two decades.

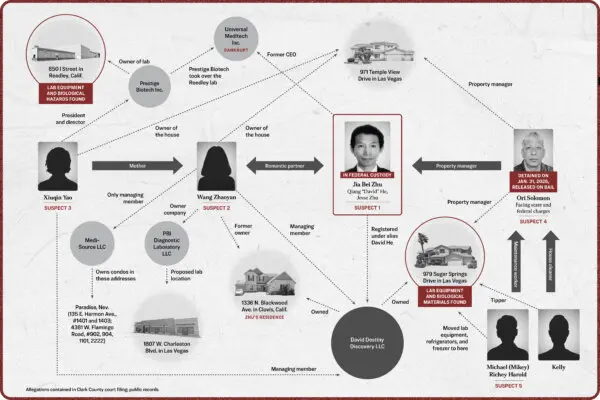

The FBI last May arrested two suspected Chinese agents who had tried to bribe an FBI agent posing as an IRS official with tens of thousands of dollars in an attempt to revoke Shen Yun’s nonprofit status.

The Department of Justice indicated that the two alleged CCP agents had also sought to use an environmental lawsuit targeting the company’s training facilities and schools to “inhibit” their growth.

The next attack against Shen Yun, however, appears to be coming from the United States’ largest newspaper, The New York Times.

Two reporters, Michael Rothfeld and Nicole Hong—the latter of whom began to work on the Shen Yun story after spending six months at The New York Times’ China desk—have specifically sought out former artists who might have left the company years ago with a grudge, records obtained by The Epoch Times suggest.

Many of Shen Yun’s artists are practitioners of Falun Gong, a meditation practice whose followers are brutally persecuted by the CCP—making the company a prime target of the regime and its proxies. Some of Shen Yun’s dance pieces include artistic depictions of the persecution.

“We know these reporters are targeting for interviews a tiny group that might have something bad to say about Shen Yun, and seem to be ignoring the overwhelming majority [of artists] who see their time at Shen Yun positively and [as] deeply rewarding,” Ying Chen, a vice president of Shen Yun, told The Epoch Times.

“We also know some of these interviewees have freely traveled to China, which raises a huge red flag because normally anyone who works for Shen Yun or is known to practice Falun Gong would be in grave danger going back to China—but these folks do so freely and repeatedly. We also have records of communication that demonstrate some of these interviewees were very happy with their experience at Shen Yun, but now are saying the opposite to The New York Times.

Out to Smear

The Party considers the Shen Yun campus in upstate New York, called Dragon Springs, a “headquarters” of activities by Falun Gong practitioners to counter the persecution.A CCP directive document obtained by The Epoch Times calls to “systematically strategize to attack” Falun Gong’s “headquarters.”

Another document directed officials to co-opt specific industries for its transnational repression against Falun Gong, calling for mobilization of “China-friendly people such as experts, scholars, journalists ... who have greater influence in the U.S. and Western countries to speak for us, and strive to make more foreign media to publish more reports favorable to us.”

The New York Times now appears to be doing just that, commented Larry Liu, a deputy director of the Falun Dafa Information Center (FDIC), a nonprofit dedicated to monitoring the persecution of Falun Gong.

“This article will likely be the CCP’s dream come true,” Mr. Liu said.

Not long after Ms. Hong returned to New York last year after a stint with The New York Times’ China team in Seoul, some former Shen Yun dancers started to receive emails from her and Mr. Rothfeld. The emailed questions were at times disturbingly specific and left the artists with the impression the reporters were trying to dig up information that could be weaponized against the company, Mr. Liu said.

One former dancer was only asked about one specific incident: a knee injury.

According to Mr. Liu, the reporters seem to be trying to craft a narrative suggesting that the dancers don’t receive sufficient medical care, a key false narrative pushed by the CCP to malign Falun Gong.

The Epoch Times spoke to dozens of Shen Yun artists and their family members as well as students and teachers at two schools affiliated with Shen Yun. They described the environment as demanding but with a healthy culture and supportive community. The suggestion of lacking medical care or treatment prompted visceral responses.

“It’s absolute rubbish,” said Kay Rubacek, whose son and daughter perform with Shen Yun. Ms. Rubacek is a filmmaker whose portfolio includes award-winning documentaries and the program “Life & Times” on NTD, a sister outlet of The Epoch Times.

“Everyone who watches the show, sees Shen Yun, they can see that these dancers love it. They really love what they do.”

Her children started attending Fei Tian Academy of the Arts, a grade 5–12 private art school, when they were 13 and 14. Ms. Rubacek said that before sending her children to the school, she was very particular about becoming familiar with the campus and the teachers.

“I’m very careful with where I send my kids. I’m very protective of them,” she said. “So for me to feel comfortable for them to go to a boarding school, I have to check everything, and I checked everything.”

The dance track at the school gives students the possibility of auditioning for Shen Yun while training at the Fei Tian College on the same campus, which is what her children did—with great success, she noted.

She recalled that shortly after joining the school, her son hit his toe during dance practice. He was taken for an X-ray, which revealed a hairline fracture. His dance teacher insisted he couldn’t join the class again until the fracture had fully healed.

He took the hiatus as an opportunity to focus on stretching, becoming one of the most flexible dancers in the troupe, she said.

“The level of positivity that I see coming from them and their ability to face challenges is pretty remarkable and something that I wish I had as a kid,” Ms. Rubacek said.

She was appalled to learn that The New York Times would try to smear her children as being part of some opprobrious organization.

‘Real Danger’

“The false narratives that the [New York] Times seems to be pursuing are a grave concern for us because it can create real danger,” said George Xu, vice president of Dragon Springs.Several months ago, he said, local and federal authorities were mobilized to counter what they believed was a credible threat posed by a Chinese man who posted to social media about wanting to be part of a “death squad.” The man also posted a video of himself loading AR-15 rifle magazines.

The man “propagates these same false narratives and had been speaking with some of the same individuals the [New York] Times is interviewing,” Mr. Xu said.

“At one point, this man was known to be in the area of our campus. ... We had state police patrolling our entrances, and everyone was on high alert. This is very serious.”

The Epoch Times obtained a copy of a September FBI officer safety bulletin stating that the man, who “has made threats to the Dragon Springs campus,” was seen in the area and was “potentially armed and dangerous.”

Aiming for the Top

Shen Yun prides itself as the leading Chinese classical dance company in the world, growing from one group in 2007 to eight, each with its own orchestra, touring the world and performing for more than a million people every year. The Epoch Times has been a long-time media sponsor of Shen Yun.As with any elite artistic endeavor, classical Chinese dance requires enormous effort, said multiple dancers and teachers.

“To become an artist of such a high caliber, it definitely takes a lot of grit and a lot of persistence, and you have to sacrifice a lot of time and energy,” said Alison Chen, who retired from Shen Yun in 2015 to become a dance teacher and later co-chair of the dance department at Fei Tian College’s campus in Middletown, New York.

She was still in her teens when she started training with Shen Yun in 2007, shortly after its inception. Thanks to her aptitude and previous dance experience, she was invited to join the touring company fairly quickly as part of her school practicum. Over the years, however, the company has continued to raise the bar. Fei Tian students are still allowed to audition for tours as part of their coursework, but their dance skills must be exceptional for them to make the cut, she said.

Compared to ballet, classical Chinese dance training is more aligned with the natural disposition of the human body, leading to less extreme strain, said Jimmy Cha, who was a professional ballet dancer before he joined Shen Yun in 2008.

According to those estimates, a professional dance company the size of Shen Yun would theoretically have hundreds of injuries occurring every year.

The dancers and teachers The Epoch Times spoke to didn’t have such statistics ready, but all agreed the injury incidence they observed in Shen Yun was a fraction of that number.

Mr. Cha attributed the low injury rate partly to the rigorous training standards and emphasis on correct technique. Rather than a dance move itself leading to injury, it’s often the dancer’s incorrect technique that over time leads to excessive strain or injury, he explained.

“Keeping everyone in tiptop shape and having their technique constantly monitored helps avoid many problems,” he said.

Already in his 40s, Mr. Cha has had his share of dance injuries. The last one, a torn ligament in his knee in 2020, threatened to end his career. He flew to South Korea to see a world-class knee surgeon, he said, and after extensive rehabilitation, he was able to return to the stage.

If a physical issue stops a person from continuing as a performer, Shen Yun often offers him or her the chance to stay with the company in a different role, such as production, Mr. Cha said.

Yet in most cases, it’s not the physical rigors that those who choose to drop out find insurmountable. Rather, it’s the mental and even spiritual challenge.

In general, the world of elite performing arts is notorious for internal politics and intense competition, with clashing egos and accomplished artists feeling slighted if passed over for leading parts, multiple dancers acknowledged.

They noted a much different atmosphere at Shen Yun.

In order to portray authentic Chinese culture, the artists need to study it and embody it themselves, adhering to traditional values and morality. Most importantly, they need to leave their egos at the door, they said.

Having grown up in the strictly hierarchical society of South Korea, Mr. Cha noted it took some adjusting for him to take advice from younger dancers or even teachers.

Ms. Chen said, “The teachers would tell us, ‘No matter how much you have learned and no matter how much you think you know, we all have to start from ground zero.’”

Adopting a humbler attitude toward dance was a process, she said.

She recalled how her ego swelled after she won in the junior division of a classical Chinese dance competition.

“I thought it was a means for me to get famous,” she said.

It was a crucial moment in her budding career, one where, in retrospect, she realized her character was put to the test.

“If no one really guided me to think about this in a healthy manner, very easily I could have still held on to that,” she said.

Thanks to the positive influence of her teachers and classmates, she was able to recognize the issue, she said.

“Xue wu zhi jing”—learning is limitless—goes a Chinese proverb she would recite to herself.

“The more arrogant you are, the less you will be able to grow,“ she said. ”No matter how great you think you are, there’s always someone who can teach you something new.”

But knowing the wisdom and putting it into practice are two different things, she observed.

The following year, when she finished second in the competition, she felt unsettled in her heart.

“Regardless of how much I might have denied it, more or less I still cared about it,” she said.

Things took a turn for the worse. Unlike her normally “happy-go-lucky” self, she was becoming self-conscious and nervous on stage.

“The more I cared about how I looked in public, the more stressed I felt when I performed, and sometimes that would affect the quality of my performance onstage,” she said.

At a certain point, she found herself at a crossroads: either let go of her vanity, or go down a road of resentment, envy, and finger-pointing. After much self-reflection, she chose the former.

“I realized ... I had to really take a step back and work on myself internally first before I could keep moving on,” she said.

She found the choice deeply liberating.

“It actually taught me to be more grateful,” she said.

But not everyone can make that leap. Those who don’t are likely to eventually leave, several company members said.

There have been some less-than-amicable partings over the years, typically because a member violated company rules, couldn’t make the cut artistically, or demanded special recognition or treatment, they said.

Suspicious Activity

The New York Times’ efforts grew more alarming to Mr. Liu when he learned that Ms. Hong and Mr. Rothfeld were talking to Alex Scilla, a man with long-standing business interests in China who has been running an extensive campaign against Dragon Springs together with local activist Grace Woodard.After two previous suits were dismissed, Mr. Scilla filed a new one, which is, again, unsubstantiated, Dragon Springs representatives said, walking The Epoch Times through the evidence.

Prior to launching the IRS scheme, they also pursued activities that appear eerily similar to Mr. Scilla’s efforts, court documents indicate.

Mr. Chen’s handlers were apparently operating from Tianjin, the base of the 610 Office, an extralegal police agency established in 1999 by the CCP to eliminate Falun Gong. His targeting of Chinese dissidents in the United States earned him growing stature within the CCP, including three audiences with Xi Jinping, the CCP’s paramount leader, according to the court documents.

“We started this fight against [the founder of the Falun Gong] twenty, thirty years ago. They are always with us.”

The reference to “the founder of the Falun Gong,” as well as the fact that Mr. Chen and Mr. Lin aimed their bribery scheme at the Orange County IRS office, left no doubt that the targeted entity was Shen Yun, Mr. Liu said.

Mr. Scilla has his own ties to Tianjin. Based on information reviewed by The Epoch Times, he lived in the northern Chinese metropolis for many years, and his only potential source of income appears to be a consultancy firm he founded with his Chinese wife in Tianjin in 2019, shortly after he moved to the United States and launched his campaign against Dragon Springs. Mr. Scilla didn’t respond previously to multiple inquiries from The Epoch Times.

Mr. Chen claimed to also have a business in Tianjin and indicated to the undercover FBI agent that he may want to travel to China and get paid there, “stating that his access to resources in [China] dwarfed what he had access to in the United States,” prosecutors said.

A History of Toeing the Party Line

In 2001, The New York Times’ then-publisher, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., led a delegation of the paper’s writers and editors to Beijing, where they negotiated with the CCP to unblock the paper’s website within China. A few days after the newspaper published a flattering interview with then-CCP leader Jiang Zemin, the website was unblocked.In 1999, Jiang personally launched the campaign to “eradicate” Falun Gong, against the wishes of other top CCP officials.

As the persecution raged with escalating ferocity, both The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal were producing hard-hitting coverage of the regime’s atrocities and exposing the Party’s propaganda meant to demonize Falun Gong.

The New York Times took the opposite tack, lending extensive real estate to the regime’s propaganda.

In one case, the paper went as far as parroting the line that Falun Gong practitioners benefited from the CCP’s attempts to brainwash and coerce them into renouncing their faith.

One Falun Gong practitioner, who was “still in the prison camp,” was “quoted as saying that ‘the re-education center is more comfortable than my home’ and that ‘police in the center are very polite and kind,’” one article said.

Nearly two-thirds of the paper’s articles on Falun Gong over the past 25 years have included various falsehoods and misrepresentations, usually lifted from the CCP’s lexicon, according to an upcoming report by the FDIC obtained by The Epoch Times.

Dozens of articles have labeled Falun Gong as a “cult,” “sect,” “evil cult,” or “evil sect.”

In some cases, the paper acknowledged the labels came from the CCP, but in others, it assigned them in its own voice.

Scholars of Chinese religion, human rights researchers, and even journalists who ventured to familiarize themselves with Falun Gong have concluded that such labels are unwarranted.

Ian Johnson, who authored a groundbreaking series of reports on Falun Gong for The Wall Street Journal in 2000, observed that the practice “didn’t meet many common definitions of a cult.”

“Its members marry outside the group, have outside friends, hold normal jobs, do not live isolated from society, do not believe that the world’s end is imminent and do not give significant amounts of money to the organization. Most importantly, suicide is not accepted, nor is physical violence,” he wrote.

“[Falun Gong] is at heart an apolitical, inward-oriented discipline, one aimed at cleansing oneself spiritually and improving one’s health.”

Only in a handful of articles has The New York Times managed to include the most basic explanation of Falun Gong’s beliefs—its core tenets of truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance.

As more evidence of the brutalities against Falun Gong amassed, the paper simply ignored it, according to the FDIC.

In 2016, a New York Times reporter, Didi Kirsten Tatlow, met with several Chinese transplant doctors and overheard their conversation suggesting that prisoners of conscience were used in China as a source of organs for transplants. Around the same time, some human rights lawyers and researchers already had collated substantial evidence indicating that the CCP was indeed killing prisoners of conscience to fuel its booming transplant industry, and that the primary target was Falun Gong.

Ms. Tatlow was ready to pursue the investigation but said she was blocked by her editors.

The panel’s final judgement burned through the media, sparking reports in The Guardian, Reuters, Sky News, the New York Post, and dozens more.

“The New York Times, however, was silent,” the FDIC noted.

In recent years, the paper’s coverage of Falun Gong turned “openly hostile,” it said.

In 2020, playing into the anti-racism fervor at the time, the paper included a claim that Falun Gong prohibited interracial marriage—an obvious falsehood, as interracial marriages are common among Falun Gong practitioners.

Articles also portrayed Falun Gong as “secretive,” “extreme,” and “dangerous” without bothering to substantiate the claims, the report said.

History of Propaganda

The New York Times has a sordid history of amplifying communist propaganda.In the 1930s, its star Russia reporter, Walter Duranty, infamously covered up the Soviet-induced famine in Ukraine and even collected a Pulitzer Prize for it.

In private conversations, Duranty affirmed he was aware of the famine, according to “US Intelligence Perceptions of Soviet Power, 1921–1946” by Soviet expert Leonard Leshuk.

Duranty told a U.S. State Department official in Berlin “that ‘in agreement with The New York Times and the Soviet authorities’ his official dispatches always reflect the official opinion of the Soviet regime and not his own,” Mr. Leshuk wrote.

Decades later, the paper commissioned a consultant to determine whether the Pulitzer should be returned. The consultant concluded it should, but the paper refused to do so.

The Duranty fiasco wasn’t an isolated incident, according to “The Gray Lady Winked” by Ashley Rindsberg.

“The paper published blatantly pro-Communist propaganda as news reports during the early critical years of the rise of the Soviet Union,” and continued to do so well into the Soviet years, Mr. Rindsberg wrote.

“The New York Times regularly carried news reports and analyses written by communist agents and Soviet sympathizers. If the Times’ leadership felt the pro-Soviet reporting was inaccurate or misleading, they certainly never did anything about it.”

Mao Zedong, whose dictates caused the deaths of an estimated 80 million people, was once hailed by the paper as a “democratic agrarian reformer.”

“The social experiment in China under Chairman Mao’s leadership is one of the most important and successful in human history,” David Rockefeller wrote in a 1973 op-ed for the paper.

When Fidel Castro was about to clinch power in Cuba, The New York Times helped to prop up his image too, calling him “democratic.” The paper’s publisher even met with Castro at the time. The communist dictator was welcomed to the paper’s headquarters again in 1995, flanked by favorable coverage of his U.S. visit, and yet again in 2000, Mr. Rindsberg wrote.

Tom Kuntz, former editor at the paper, was “concerned” at seeing Castro enjoying an ecstatic welcome at the offices, with crowds of staffers following the dictator around.

CCP Leverage

Ever since The New York Times’ previous publisher, Mr. Sulzberger, decided to take the publication global, its presence in China has been a high priority, with the paper maintaining bureaus in Beijing and Shanghai. That access, however, appears to come with strings attached.“There’s always the issue of, if you want to be a global newspaper, what do you have to do to keep China happy and stay in business there?” Mr. Kuntz said.

“There’s always been tensions, and I know they’ve, like a lot of companies, tried to maintain access to China.”

In 2012, the paper ran an exposé on the family wealth of Wen Jiabao, then Chinese premier and one of the last voices for even mild political reform among the Party leadership.

The CCP responded by blocking the New York Times website, including its Chinese version that had launched just a few months before.

The paper’s executives, including Mr. Sulzberger, tried to persuade the Party to renew access.

Then-executive editor Jill Abramson later complained in her book that Mr. Sulzberger went behind her back and, “with input from the Chinese embassy, was drafting a letter from the [New York] Times to the Chinese government all but apologizing for our original story.”

“The draft in my view was objectionable and said we were sorry for ‘the perception’ the story created. My blood pressure rose as I read it,” she wrote.

When she confronted the publisher, he kept repeating, “I didn’t do anything wrong” and agreed to redraft the letter, she said.

The final version was still “objectionable,” Ms. Abramson wrote.

“The word ‘sorry’ remained in the final draft of the letter that I saw.”

After 2012, The New York Times’ insistence on “penetrating the mainland Chinese market” led to a slew of new initiatives, including print publications, newsletters, and a lifestyle site, Mr. Smith wrote.

By 2019, the paper’s Chinese offices employed dozens of reporters, some native Chinese, some correspondents—the largest presence the paper held in any overseas locale.

Then the virus came.

In February 2020, The Wall Street Journal ran an op-ed by Walter Russell Mead headlined “China Is the Real Sick Man of Asia.” It panned China for mishandling the coronavirus epidemic and questioned Beijing’s power and stability.

The next day, an explosive request landed in the mailbox of The New York Times’ ad department. Florida real estate developer Brett Kingstone wanted to publish a full-page ad calling China to account for the pandemic.

The ad was scheduled to run on March 22, 2020. It had been approved, paid for, printed, and distributed in the early editions before the paper suddenly pulled the plug in the middle of the night, preventing the ad from running in most print copies.

“It was removed after being flagged internally by [New York] Times staff.”

She didn’t respond to a question about whether the paper had faced any pressure from the CCP regarding the ad.

Mr. Kingstone said a New York Times executive told him that a CCP official had called the paper’s leadership and demanded that the ad be pulled. The Epoch Times wasn’t able to independently confirm that the phone call took place. Attempts to reach the executive for comment were unsuccessful. The paper’s spokesperson neither confirmed nor denied that such a phone call took place.

Pat Laflin, a former FBI agent and expert on economic espionage, said it was “impossible” that the CCP didn’t try to pressure the paper.

“Exactly what they said and how subtle it was or how not-so-subtle, that’s all speculation. I don’t know,” he said. “But did the call come in? Yes.”

The day after Mr. Kingstone’s ad was pulled, on March 23, 2020, the executive editors of The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and The New York Times published an open letter to the Chinese regime, pleading to have the expulsions reversed.

In November 2021, the Biden administration relaxed restrictions on Chinese media in exchange for the CCP allowing reporters for The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal to return and travel to and from China more easily.

The op-ed was an endorsement of the failed policy of “engagement” with China, according to Bradley Thayer, a senior fellow at the Center for Security Policy, expert on strategic assessment of China, and a contributor to The Epoch Times.

He blamed The New York Times for “ideological obtuseness where they refuse to see the nature of communist regimes as they are.”

From another perspective, The New York Times has a vested interest in avoiding confrontation with China simply because it wants to maintain access, said James Fanell, former naval intelligence officer and an expert on China.

“I think it’s that obvious,” he said.

The Epoch Times sent The New York Times 13 specific questions when asking for comment regarding the allegations outlined in this article. The questions covered topics including why its reporters appeared to seek out only negative interviews; the paper’s previous misrepresentations of Falun Gong based on CCP propaganda; and how portraying Shen Yun in a negative light potentially could help the CCP in its efforts to suppress dissent at home and abroad.

The New York Times declined to respond to any of the questions, saying only, “As a general matter of policy, we do not comment on what may or may not publish in future editions.”