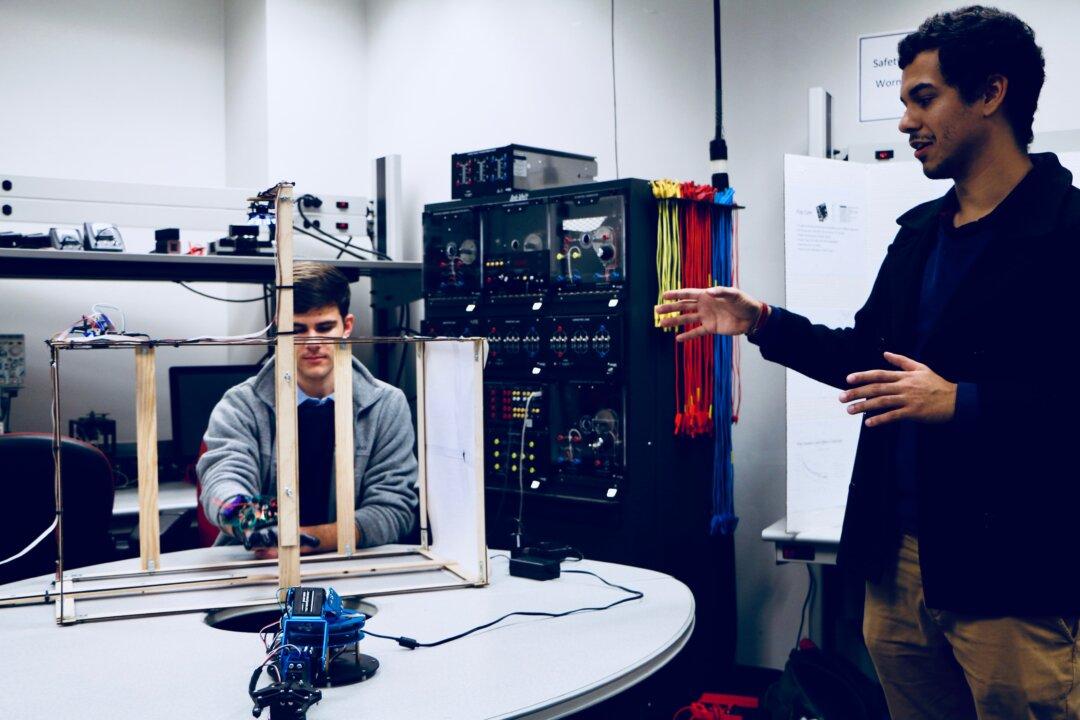

The University of Florida recently announced the creation of the Florida Semiconductor Institute (FSI), a campus and state-wide network to establish critical infrastructure in the Sunshine State and make it a world leader in microchip manufacturing during an international chip shortage.

According to FSI, the project aims to lead, advise, and coordinate with Florida on all matters related to semiconductors, or microchips—their design, manufacturing, and implementation.