New Dynamics in Syrian Civil War

U.S. involvement in Syria has been limited. Rebels could win a quick victory with the right weapons, but the West is wary of terrorist groups obtaining those weapons.

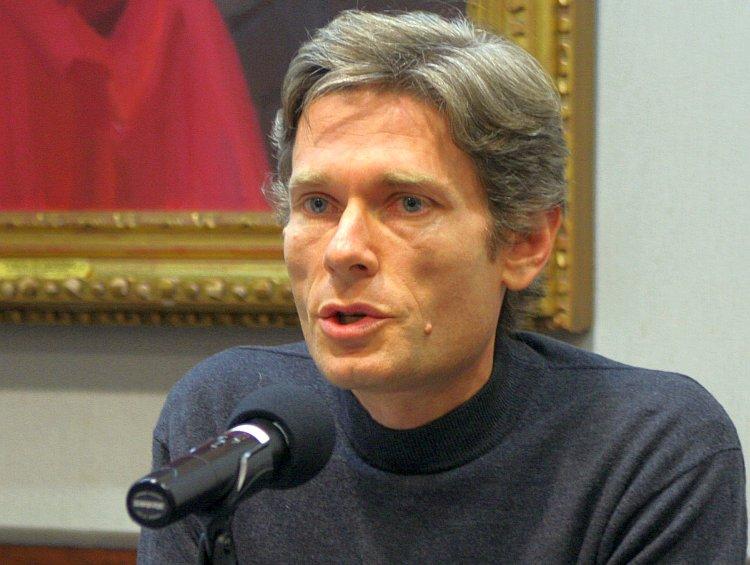

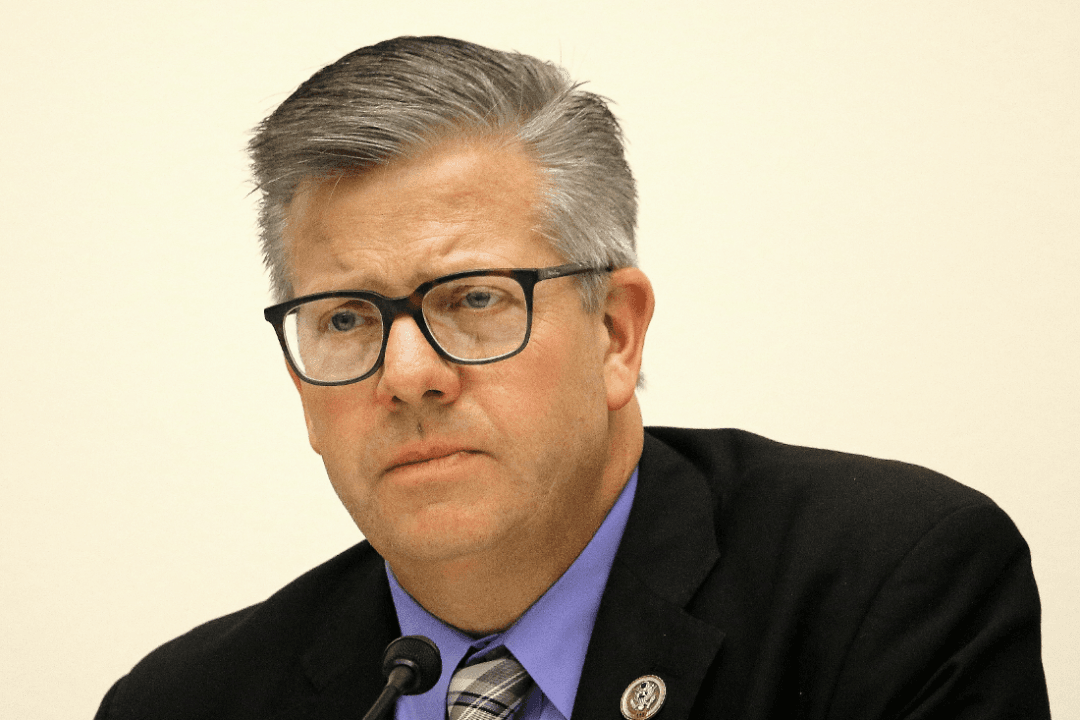

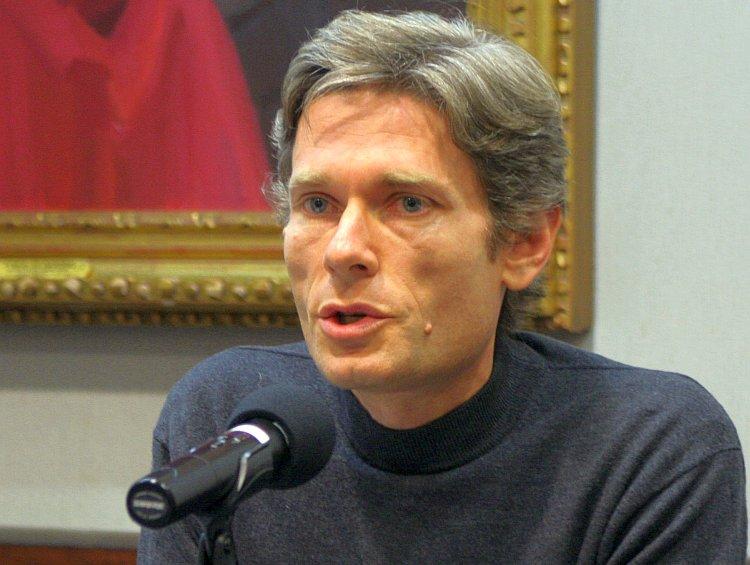

Rep. Tom Malinowski in a file photo. Gary Feuerberg/ The Epoch Times

|Updated: