The Navajo Nation has become the first area in the country to approve a tax on junk food, pairing it with the elimination of sales tax on fruits and vegetables to try to compel people to eat healthier.

The Nation comprises an area of over 27,000 square miles, across the states of Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico.

Bags of chips and Hot Cheetos, among other items such as sweetened beverages and fried foods labeled as junk food, will cost 2 percent more under the tax. Meanwhile, the 5 percent sales tax won’t apply to fresh fruits and vegetables.

The tax was approved by the Nation to try to combat a health crisis—an estimated 100,000 of the tribe’s 300,000 members either have Type-2 diabetes or are pre-diabetic.

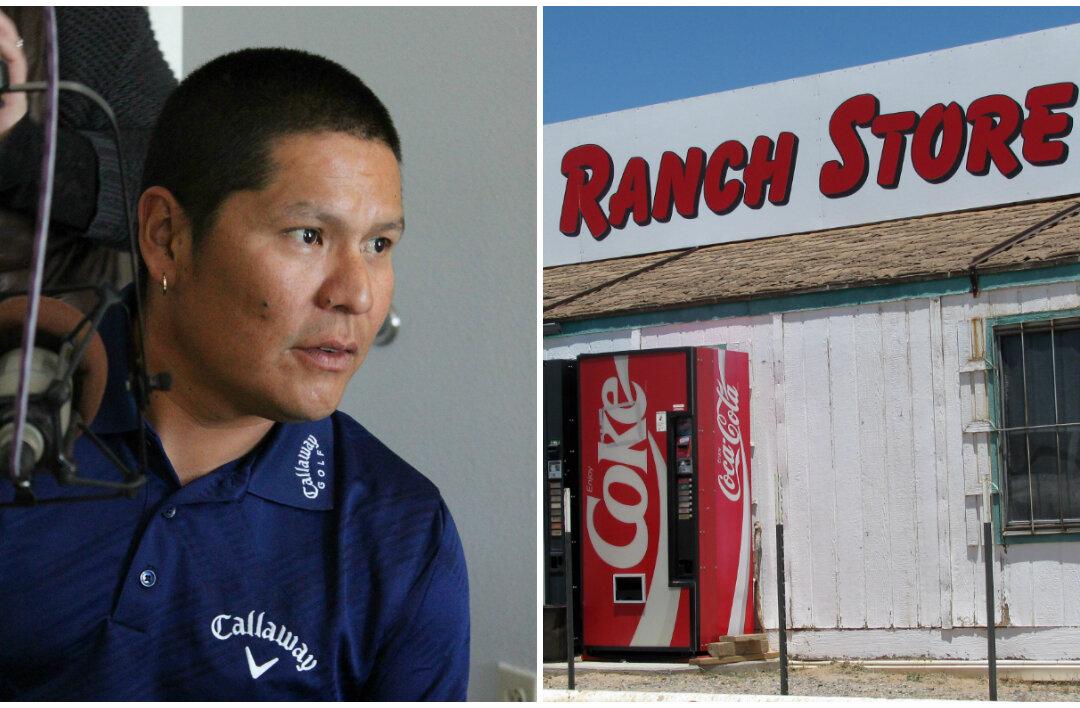

“The trend of obesity and diabetes is soaring very quickly, so we need to put some kind of stopgap measure on that,” Gloria Ann Begay, a founding member of the Dine Community Advocacy Alliance, which approved the act, told the Indian Media Network. An alliance survey found that up to 80 percent of the food stocked by grocery stores on the reservation qualifies as junk food, prompting more than half of Navajo residents to travel off the reservation to purchase groceries. Also, only 10 grocery stores serve the area, which is approximately the size of the state of West Virginia, leading the U.S.Department of Agriculture to term the area a “food desert.”

“Most residents are driving upward of two hours or more to get to a grocery store,” said Michael Roberts, president of First Nations Development Institute, an organization that works with the alliance.

While some measures across the United States have taxed soda in stores or vending machines, none have as of yet gone so far as this new act to tax both sugary foods and drinks. The act runs through 2020, but could be extended.