WINSLOW, Ariz.—On a desert outpost miles from the closest paved road, Navajo students at the Little Singer Community School gleefully taste traditional fry bread during the school’s heritage week.

“It reminds us of the Native American people a long time ago,” says a smiling 9-year-old, Arissa Chee.

The cheer comes in the midst of dire surroundings: Little Singer, like so many of the 183 Indian schools overseen by the federal government, is verging on decrepit.

The school, which serves 81 students, consists of a cluster of rundown classroom buildings containing asbestos, radon, mice, mold and flimsy outside door locks. The newest building, a large, white monolithic dome that is nearly 20 years old, houses the gym.

On a recent day, students carried chairs above their heads while they changed classes, so they would have a place to sit.

These are schools, says Interior Secretary Sally Jewell, whose department is responsible for them, “that you or I would not feel good sending our kids to, and I don’t feel good sending Indian kids there, either.”

Federally owned schools for Native Americans on reservations are marked by remoteness, extreme poverty and few construction dollars.

The schools serve about 48,000 children, or about 7 percent of Indian students, and are among the country’s lowest performing. At Little Singer, less than one-quarter of students were deemed proficient in reading and math on a 2012-2013 assessment.

The Obama administration is pushing ahead with a plan to improve the schools that gives tribes more control. But the endeavor is complicated by disrepair of so many buildings, not to mention a federal legacy dating to the 19th century that for many years forced Native American children to attend boarding schools.

Little Singer was the vision in the 1970s of a medicine man of the same name who wanted local children educated in the community.

Students often come from families struggling with domestic violence, alcoholism and a lack of running water at home, so nurturing is emphasized. The school provides showers, along with shampoo and washing machines.

Conflicts and discipline problems are resolved with traditional “peacemaking” discussions, and occasionally the use of a sweat lodge.

Principal Etta Shirley’s day starts at 6 a.m., when on her way to work, she picks up kids off the bus routes. Because there’s no teacher housing, a caravan of teachers commutes together about 90 minutes each morning on barely passable dirt roads.

All this, to teach in barely passable quarters.

“We have little to work with, but we make do with what we have,” says Verna Yazzie, a school board member.

The school is on the government’s priority list for replacement.

It’s been there since at least 2004.

* * *

The 183 schools are spread across 23 states and fall under the jurisdiction of the Interior Department’s Bureau of Indian Education.

They are in some of the most out-of-the-way places in America; one is at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, reachable by donkey or helicopter. Most are small, with fewer than 150 students.

Native Americans perform better in schools that are not overseen by the federal bureau than in schools that are, national and state assessments show. Overall, they trail their peers in an important national assessment and struggle with a graduation rate of 68 percent.

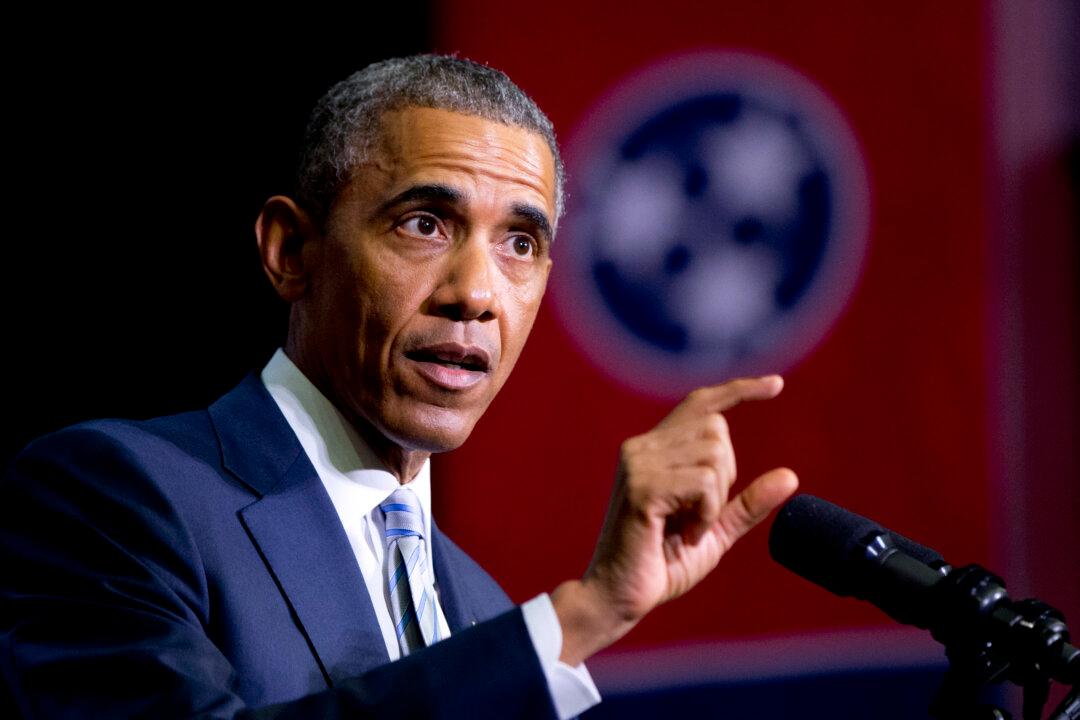

President Barack Obama visited Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota in June, where he announced the school improvement plan.

Already, tribes manage about 120 schools, and the plan will turn the rest over as Washington shifts to more of a support role.

The plan also calls for more board-certified teachers, better Internet access and less red tape, making it easier to buy books and hire teachers. The Interior Department wants to help schools accelerate the use of Native American languages and culture.

But the rundown state of many schools cannot be ignored.

More than 60 are listed in poor condition. Less than one-third have the Internet and the computer capability to administer new student assessments that are rolling out in much of the country.

An estimated $1.3 billion is needed to replace or refurbish these schools, or at least hundreds of millions to fix parts of them. But since the 2009 release of about $280 million in stimulus money, little has gone to major school construction or renovation.

So Jewell is in a tight spot.

She recently visited Crystal Boarding School on the Navajo reservation in Crystal, New Mexico, where some classes are held in a building constructed by Depression-era workers.

The school is now primarily a day school, but about 30 kids stay in dorms there, in part because they live too far to catch buses that begin running at 5:30 a.m. There’s a waiting list for dorm space, but a second dorm was condemned.

Jewell was met by hugs from the kids, who performed songs in the Navajo language. She thanked the students for “making do with this school the way it is.” Later, she told school leaders she couldn’t promise the money will be there to build a new school.

“For schools throughout Indian country, this is a chronic problem,” she said. “I don’t want to stand here and make promises I can’t keep. What I want to say is, I get it.”

* * *

These schools are the legacy of 19th century assimilation policies that still exist, in part, because of the government’s treaty and trust responsibilities.

Thousands of Native American children were once taken from their homes — some forcibly — to attend boarding schools far from their families. That was the case for many parents of current students in the bureau’s schools; some were as young as 5 when they went away.

Marie Williams, personnel coordinator and special education teacher at Little Singer, said she and her boarding-school mates were pulled so far from their roots that when they watched a John Wayne movie, they celebrated when the Indians were killed. She grew ashamed of her background, she said, only embracing her Navajo heritage when she went to college.

“That kind of scarring and longtime mistrust is something that is hard to understand if you are an outsider,” said Don Yu, an Education Department official brought in to help the Interior Department improve the schools. “Any kinds of changes to the system, even under this administration, it will be met with a lot of skepticism.”

Other complex issues are at play, too, including the difficulty persuading teachers to work in remote reservations where quality housing is lacking.

One commission after another has tried to fix things. A panel in the 1920s said the students should be treated as “human beings.” The late Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Mass., took a run at the issue with another commission, in 1969.

The effort to shift more control to tribes has drawn praise from some school leaders. “It’s an important step for us to go ahead and take control over what we know we can do best,” says Kimberly Dominguez, Crystal’s vice principal.

Others, though, say Washington is merely washing its hands of its responsibilities.

Aubrey Francisco, 40, who attended Crystal and sends his 6-year-old son there, questions whether Navajo leaders can continue the school’s legacy. “With the tribe and its limited resources, they need to take that into account,” he said. He credits the school with preparing him for a career in the Navy.

Ahniwake Rose, executive director of the National Indian Education Association, said her organization is cautiously optimistic, partly out of appreciation that Obama is seemingly engaged — a rarity for a president, she said.

At Little Singer, Shirley, the principal, said she has some optimism, too, despite being let down so many times.

One glimmer of hope: A House spending bill contains nearly $60 million for construction at Little Singer and two other bureau schools. All school officials can do is wait and see if Congress provides the estimated $20 million it would take to build a new school.

“We need to get the kids out of the environment,” Shirley said. “That’s what’s really driving this. I lose sleep over it, just thinking about it.”

From The Associated Press